Former Marine Andy Grant had his life changed forever in 2009 when on a routine foot patrol in Afghanistan he was blown up by an IED (improvised explosive device). He suffered extremely serious injuries, chiefly the severing of the femoral artery in his right leg and was left in a coma for 10 days before he woke to realise just what had happened. While for many this would seemingly be the end of a normal life, for Andy Grant in many ways it was just the beginning.

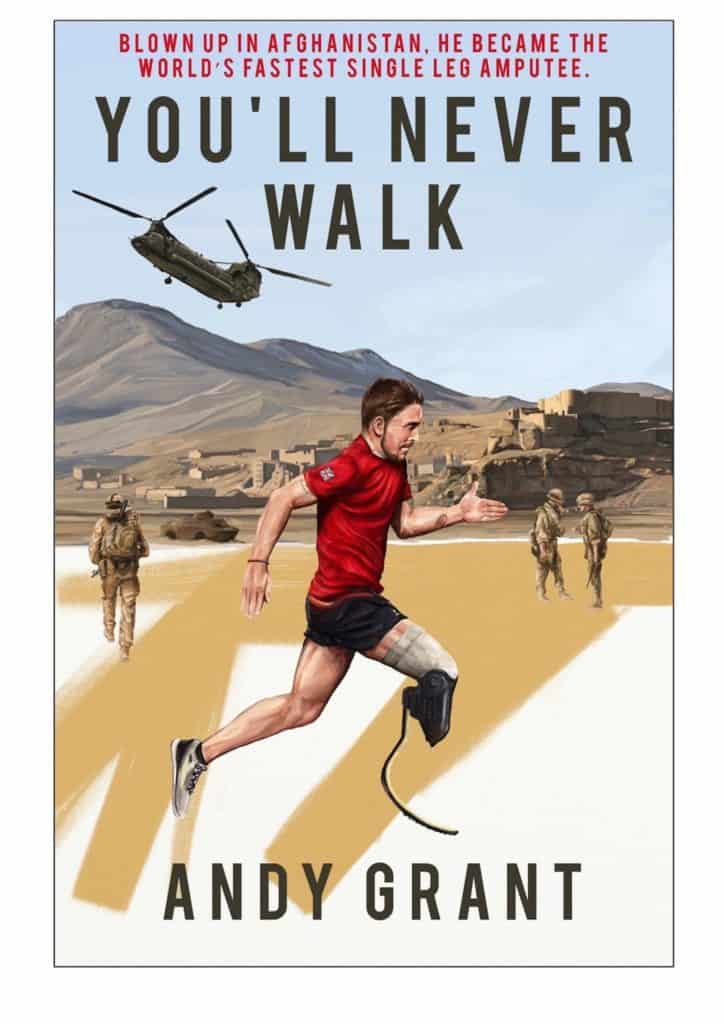

He turned his situation around in inspirational fashion and has written a gripping account of the challenges he’s faced and overcome in his life in the book, You’ll Never Walk. Andy spoke to us recently to detail that fateful day when he suffered those life-threatening injuries and how after eventually undergoing surgery to amputate his damaged leg he took up running and became a world beater.

The MALESTROM: Tell us about how you came to join the Marines? Where were you at that point, at that stage in your life?

Andy Grant: I was seventeen at the time and I was going through the motions of sixth form. I didn’t really have any great desire to go to university I just thought I’ve got the grades why not do A-levels and just hopefully fall into a career or fall into a course at university that hopefully would lead to a career. As a child, I was very sporty, very active and outdoorsy and I think it was a mix of my head not being in sixth form and then seeing this advert for the Royal Marines.

I remember sitting there with my Dad, at the end of the advert it said 99.9% need not apply and I thought do you know what I’m going to try and be the 0.01% and that was it for me really, it just got the ball rolling for me to enquire of what a potential career could look like in the Marines, I went down to the career office, then I went on a meet the Marines day, the more I found out about them the more I knew I’d be going into a career I’d love.

TM: Just how tough was the training to gain your green beret?

AG: Yeah it was incredibly tough. Physically it’s very demanding, but also mentally as well. They spend the first 15-weeks making you want to quit. I think people have this idea of the Special Forces or the Marines as these kind of great and secret techniques they must use to build up resilience, but sometimes it’s the little things, they say you always stand to attention and then you get a bottle of water poured over your head and you’ve got two minutes to run in and get changed and come back out again, they might do that three or four times and by the fourth time you just want to quit and many people do quit, but it’s just a stupid way of building up that resilience.

So there’s the mindset and the mental attitude to it, but obviously, physically you’ve got to be very, very fit, the last test being a 30 mile run, it’s progressively getting built up over 32 weeks, but as tough as it was I loved every minute of it, It’s was great brotherhood from the start and I have a lot of fond memories from training.

TM: You saw early on how brutal war could be when one of your trainers Ben Nowak was killed on duty? Did that bring to reality what you were training for?

AG: Yeah definitely. Ben was someone I looked up to, he was in charge of getting us fit, then suddenly when he went off to Iraq and never came back it was kind of like a chink in the armour where you realised we might not all be as bulletproof as we might feel at times. It was a bit of a reality check really, personally for me with him being a scouser and someone I really looked up to, it hit me hard too be honest, it was also knowing this was someone I was hopefully going to forge a friendship with in years to come, it was a sad time.

TM: How much do you remember of that fateful day in 2009 when that IED was triggered?

AG: When Iian jumped over this ditch, it was into darkness, he’s hit this tripwire and two bombs have gone off, I remember it all perfect. The first five minutes or so there wasn’t any real pain, obviously I was in shock, then I just started screaming as loud as I could, thankfully the guys on the patrol were around and they did everything they could to save my life. They placed a tourniquet on my leg which stopped my femoral artery from bleeding out and that was the start of just forty minutes of just lying there slowly dying really, with the lads doing everything they could to keep me alive till the helicopter came.

I remember the pain in my right leg, it felt like a ton of bricks was digging into my thigh, it was just a dull throbbing pain, the worst pain I’ve ever experienced, I just knew there was something seriously wrong with my leg. But again the guys on the ground just did an amazing job of keeping me talking, keeping me awake. It was that Commando humour, the things we learned in training to make the best of a bad situation.

We had a football tournament going, I was top goal scorer and they were saying, ‘you won’t be scoring any more goals now will you?’ And taking the mick out of me for going home earlier, just doing those kind of things to keep me alive. Once the helicopter came about forty minutes later that’s when they pumped all the drugs and fluids into me and I don’t remember anything after that, then I woke up ten days later.

TM: How difficult was that recovery period? You retained your right leg and had to grow bone back and try and begin to learn to walk again. How difficult was the whole process?

AG: It was tough physically, but I always felt that all I had to do was listen to the doctors and nurses and take my tablets when I was told and physically your body heals on its own, whereas mentally it was a big struggle going from doing my job fighting the enemy and stopping the bad guys to having my Dad spoon feed me cornflakes and getting my arse wiped by a young nurse. Previously I might have been trying to chat her up in a bar and now I’m getting my arse wiped by her.

It was such a strange turn of events, one minute I was in Afghanistan, the next I was waking up from a coma, I think that was the hardest thing to get my head around knowing that my career in the Marines had obviously come to an end and it was going to be a good two years of what will happen with the leg, will it heal? Will it not heal? Getting used to a wheelchair, having no social life, not being able to go on holiday, not being able to do all these things, mentally it was a lot tougher than physically.

TM: What drove you on during those dark times?

AG: I had great support from the Marines, there were a lot of injured Marines at the time and we all stuck together, I had great support from my Dan and my sisters. I think with this big cage on the leg, it was just in the hope of one day this cage is going to get taken off and my life will go back to normal. Obviously, it wasn’t meant to be and didn’t work out like that.

TM: Just how hard was that decision to have your leg amputated?

AG: I mulled it over for around six months. It was probably one of the hardest decisions I’ll ever have to make, really tough cause obviously there’s no going back, once it’s done it’s done. Secondly, my Dad was really against it, I’m his first born, his only boy, he didn’t want to see me go through more operations and more time in the hospital, he’d never met any amputees before so he had a big reluctance to it. It was just waking up every day not knowing what the next day might bring, whether my leg would be ok or whether it might hurt or not.

I mulled over it like I said for six months till I eventually thought I can’t keep living my life in this way, I need to make a decision, stick with it and move on. Having the leg amputated not only cut the leg off, but it cut short any of these what ifs? So I was in this situation now and I could just get on with my life.

TM: Running was a big part of your life that came after that decision wasn’t it?

AG: Yeah, I mean I’ve always been physically fit, being in the Marines and that, but I’ve never thought of myself as a runner. I ran cause I needed to keep fit for my job, I never thought about enjoying running, it was always just that I needed to do it. Then when I had the amputation and learned how to run, I realised just how important it was for me.

I got into running thanks to Clive Cook, he got me into running, I was at a time of my life when I was losing my way a lot, everything else was falling apart and running gave me a bit of a release, It got me setting targets for myself again, it just got me enjoying running. And I wasn’t just this guy with one leg anymore, it made me start to look at myself a little bit differently.

TM: You mention in the book about that text from Clive asking you to go running that in a way saved your life?

AG: It was a massive catalyst for getting me out there on the streets again running. If that didn’t happen who knows how far I would have gone down the rabbit hole before coming back.

TM: How big a platform to kickstart your running career was the Invictus games?

AG: it opened my eyes to the potential of what sport could do and how much of a stage I really had if I wanted to pursue it, being this successful gold medalist runner and having a story that people wanted to hear about, overcoming adversity, it kind of set me on my way that little bit more.

It was also really humbling to see these lads doing so well and it made me realise that I’m not the only one in this position, it was nice to talk to people about what was going on and to see all your friends who’d been through this shit with go on and do well themselves.

TM: How important do you think exercise is for mental health?

AG: I know obviously from my own personal account just what being in a gym and what running has done for me, but to see it first hand at somewhere like the Invictus Games where you’ve got people from all over the world with all types of traumas and significant injuries, you realise it’s not all about winning, for me one of the best moments was seeing a guy just get to the start line, never mind the finish line.

My friend Ricky who lost both his legs, lost a few fingers, lost an eye and his nose and suddenly he’s at the start line and you think, bloody hell, I remember him getting wheeled in a few weeks after getting blown up and now he’s on the starting line of an athletics track with thousands of people watching him, so there were loads of victories that came from the Invictus Games and it wasn’t only gold medals.

TM: I suppose everyone’s inspiring each other going into an event like that?

AG: Yeah, that’s the kind of line I normally use in one of my talks. The learning I came away from the Invictus Games with was you don’t always have to say anything or do anything, in particular, to try and inspire or motivate people, sometimes just being the best version of you can be automatically inspiring. And that’s what the games were, it was just people trying to do their best and people were looking at them and thinking, wow he’s doing the best he can do whether he’s one leg or no legs and that was inspiring people.

TM: How important is it for you to show that you shouldn’t limit yourself, despite the obstacles we might face?

AG: I feel it’s a good pressure I’ve got now, it’s not a negative pressure. It’s a good pressure I feel to wake up and to show people, look anything’s possible, especially in this day and age where there’s so much negativity around young people and the limits of what they can supposedly achieve. When I do these presentations I’ve got videos of me wing walking on a plane while it’s flying in the air, skiing, surfing, climbing mountains, playing football.

The idea is it doesn’t matter what’s going on from the knee down, it’s all about the top three inches, it’s all about you’re attitude and how you want to work things in your own head. I feel a bit of a pressure now, but a healthy one to show people whatever they’re going through in life, from a failed marriage to getting made redundant, that it doesn’t have to define you, it’s your attitude that will go on to define you.

TM: People reading this who haven’t read your book You’ll Never Walk yet, probably won’t know its title came from the tattoo on your leg that got modified?

TM: People reading this who haven’t read your book You’ll Never Walk yet, probably won’t know its title came from the tattoo on your leg that got modified?

AG: When I decided to go down the route of amputation, I was fortunate enough to be really good friends with a surgeon I’d served in Iraq with and he’s a bit of a legend in the Marines and the Navy. I asked him to do the amputation, obviously when the operation was done he apologised and said, “your tattoo looks a bit different”, it turns out as he pulled the skin around from the back of the leg to create a decent stump, cause my leg was so badly damaged, he’s cut off the word ‘alone’ and it now reads ‘you’ll never walk’. You learn in the Marines about Commando humour and never taking yourself too seriously, so it became a funny story I’ve been able to share with everybody.

TM: Who’s been your key inspirations in your life? Has it been your mother and father?

AG: Yeah, Mum and Dad definitely. The twelve years I had my Mum she played a massive part in my life and obviously my Dad, despite the normal Father-son relationship that everyone has really, the fallouts and all that, to see what he’s done bringing up three kids on his own is amazing. As I’ve got older in life there are also my friends in the Marines that went through similar injuries, waking up and seeing friends who’ve also been blown up crack on with their own lives, that’s inspiring as well. So I’ve tried to draw inspiration from everyone I’ve come into contact with really.

TM: From reading the book you seem to have made some famous friends. Jamie Carragher wrote the foreword and Ronnie O’ Sullivan wrote the afterword…

AG: Being from Bootle and having played left back as a kid, Jamie is always someone I’ve been a massive fan of. When I got injured, he does a lot for the community, he came to see me when I first got injured, he said one of those throwaway comments, “if you ever need anything let me know”, which you kind of expect people to say, but you never know how serious they are, but with J, he’s stuck to it and he’s done all kinds for me over the years and I count him as a mate now. I’m really lucky in that sense and when he agreed to the foreword that was great.

How Ronnie came about was quite strange. I knew him through my running coach, he was a big runner himself, he messaged me on Twitter saying, “here’s my number Andy, give us a bell if you fancy going for a run Monday”. So I gave him a call and we went for a run and some food afterward and I was on the phone to Carra about the foreword and Ronnie interjected and said, “here you are mate, I don’t mind saying something if you want me to?” So I was like, “alright, great, yeah”. So It was a bit surreal, I’m a massive sporting fan anyway, football and snooker, and to know two absolute legends like Carragher and Ronnie have had a say in my book is the stuff dreams are made of.

TM: You seem to thrive on goals, what’s next for you?

AG: Yeah, well this year we’ve raised 20k for a little boy who’s going to grow up as an amputee, so I did my first marathon and walked the Leeds to Liverpool canal to raise money for him. I’ve just come to the end of the road with that, I’m getting a bit of stick off my missus to calm down a bit and stop planning so many things.

So in the next six months I’m just going to focus on making this book as successful as possible, with the feedback being so good, keep doing my motivational talks, and in January it’ll be back to the drawing board. I’d like to try and climb Kilimanjaro next year, I think that’ll be the plan.

TM: You’ve given us plenty already, but is there a piece of wisdom you can offer to our readers?

AG: I always try and say when I look back at losing my Mum at twelve or having a leg amputated, there are so many setbacks in life, you don’t have to go to Afghanistan and be blown up to realise that life’s hard, that’s my experience. Life is 10% the situation you find yourself in and 90% what you do about it. So 90% is how you react to that setback that you face, I try and live my life by putting that into context, whatever the situation is it’s not the whole 100% it’s only 10% of it.

Read the full account of Andy’s inspirational story by buying a copy of the brilliant You’ll Never Walk HERE

Click the banner to share on Facebook