One of the great things about art, as with many things in life, is the discovery of the new. Finding a picture or photograph that may have been thought lost to the ravages of time that stirs something inside, whether it a strange sense of dread or an uplifting rush of joy.

One man who’s been responsible for bringing forth a host of eclectic art to the people is renowned curator Stephen Ellcock. Stephen is known to many through his hugely popular virtual museum on Facebook and Instagram, which have allowed him to showcase all manner of visual treasures and curiosities he’s collected from around the globe.

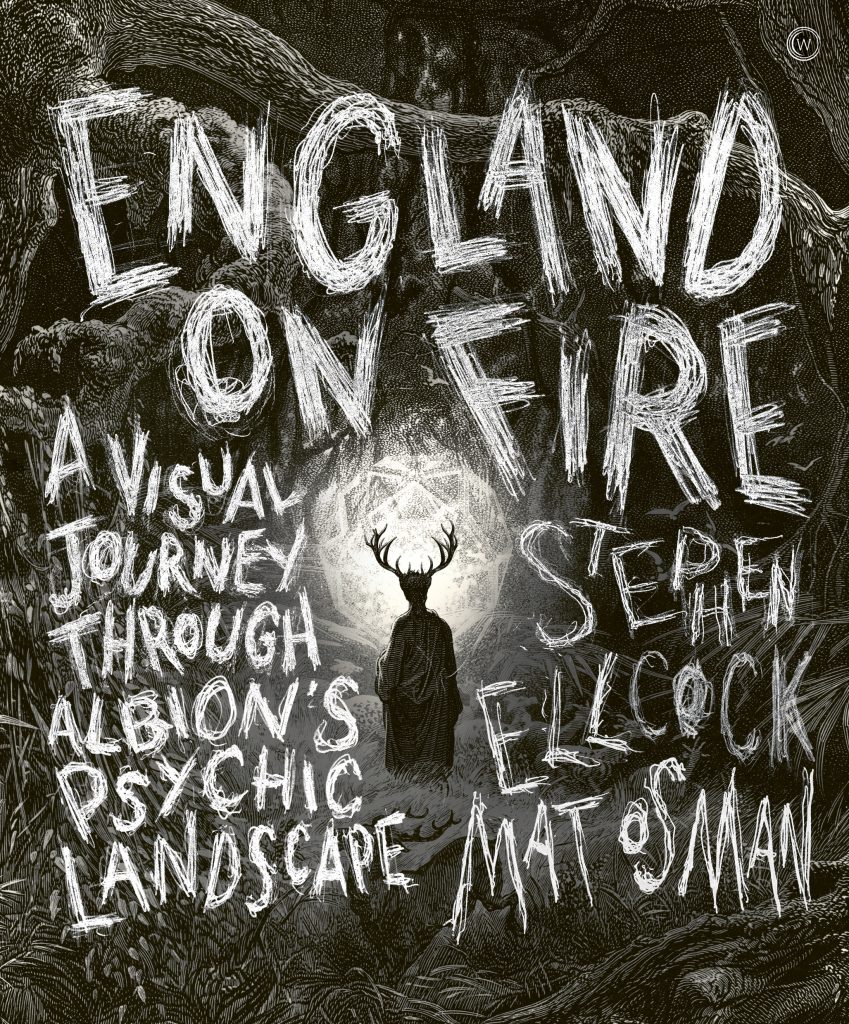

His new book, England On Fire, is a genuine feast for the eyes and the imagination. Here Stephen has selected hundreds of incredible images that take the reader on a journey through England’s psychic landscape, featuring a diverse collection of artists from William Blake and Samuel Palmer, to many previously lesser known contemporary painters, sculptors and photographers. Alongside these images sits perfect poetic prose from author and bassist of indie band Suede, Mat Osman, whose words help us explore this unique look at Albion from the supernatural to standing stones and water to wilderness.

We sat down with Stephen to talk about the idea behind England On Fire, what his research process looks like, the esoteric meaning behind the images and why this little old island is so drenched in folklore.

The MALESTROM: What was the initial idea behind England on Fire? What was the vision?

Stephen Ellcock: I was approached to do this a while ago, but more as a picture research thing. But then it mutated into something bigger than that. Watkins specialise in mind, body and spirit books, so initially I thought there would be a more spiritual angle with ghosts, fairies, lay lines, that sort of thing.

Then, when researching the images I realised there was something that hadn’t been done. There have been so many books in the last ten years about English art, but they’re all exactly the same. They all contain great artists, but there doesn’t seem to be anything that moves beyond that. The strand in English art and culture that I think is represented by the more subversive and radical elements, hasn’t been represented in any visual book other than those by individual artists.

Certainly with the things that have been going on in the last few years, like Brexit, the divisive nature of that and the sense that people are alienated from what’s going on, I thought it was really important to emphasise ,not just the continuity of the radical strands in it, but also that this is a weird place. There’s also another whole load of books, TV programmes and documentaries about old, weird Albion stuff. I didn’t think anyone needed to see another still from The Witchfinder General or Blood on Satan’s Claw, that has been done. I wanted it to be quite angry and polemical, but also to have a sense of possibility and hope at the end of it.

TM: Where do you begin to research a book like this? I guess that’s your background.

SE: Because I’ve done this for so long, well ten years. Previously I was a musician for a while and managed to blag a career in that for a few years before it all ended disastrously. Then I got a job working in a bookshop, near where I lived. Via that I was in publishing, for distributors specialising in art and illustrated books. Thats where I got to know the world of art.

I was really ill about eleven years ago with undiagnosed pneumonia, bedridden for a while and fairly isolated. People tried to persuade me to join Facebook. I wasn’t the slightest bit interested, but reluctantly I signed up and connected with some interesting people and realised you could do really great visual things with it, just mucking about with friends exchanging images. I realised it’s a way of creating this massive collage. You could make endless albums of things. I became quite obsessed and thought it’s a new way of presenting stuff that isn’t quite book form and it’s not a gallery. Publishers saw I was attracting a lot of followers and started to offer me book deals. I’ve managed to support myself through books and doing picture research for other publishers over the past few years. So through that I just know where to find things.

The difficult thing with an illustrated book like this is getting the rights to stuff. It’s a nightmare dealing with some of the museums, galleries and estates. A lot of the images in the book are actually from American institutions, through public domain and creative commons. It’s a public service from their point of view. I think that process really benefitted this book. There were loads of artists I wanted to include, but I just couldn’t because of how difficult the process was. I wanted to include a lot of contemporary artists as well. They all gave their stuff for nothing. Which was great. It also gave me the opportunity to showcase people I found on Instagram and the like. So, I hope people will discover stuff in there that’s not in the mainstream.

TM: Tell us about the themes running through England on Fire, Magic and Rebellion being two of them. How did you come up with them?

SE: Well I wanted it to be a circular narrative, where it starts in darkness and kind of ends in light. It begins with the primal, the landscape and what shaped it. It looks at the natural landscape and the eerie aspects of that like ghosts and mythical creatures. And the way the landscape may have been formed by supernatural forces.

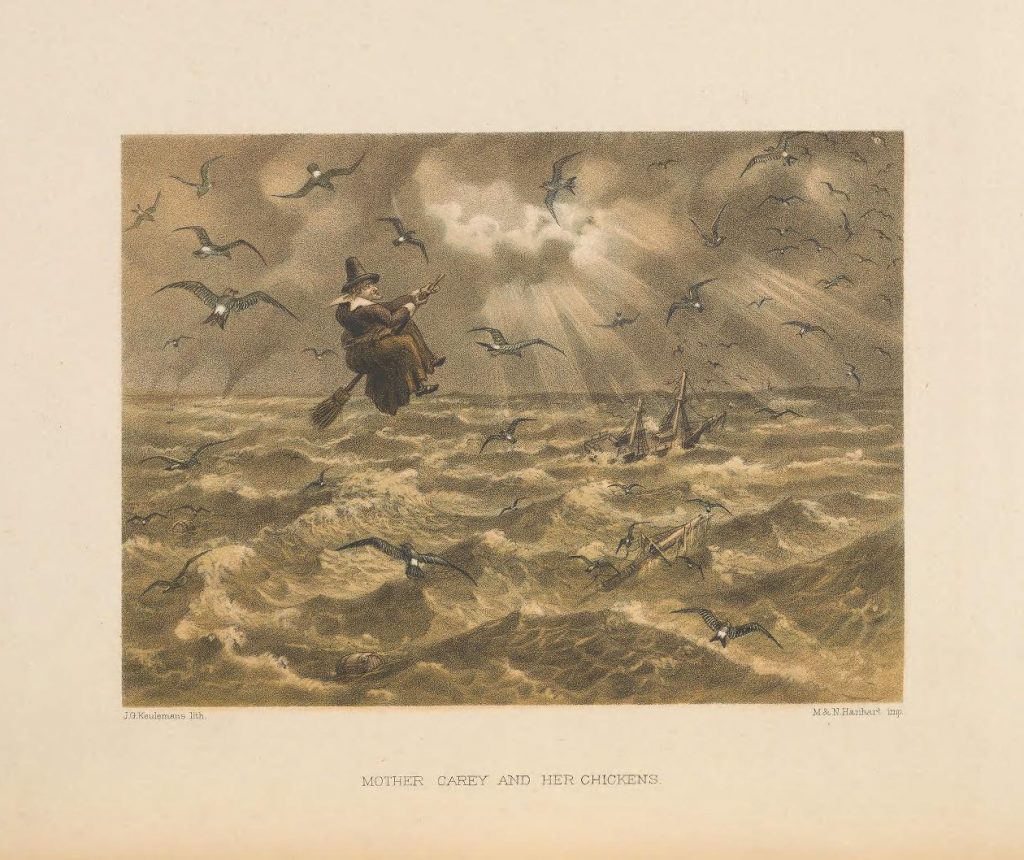

The opening chapter is quite mystical and visionary I suppose. Then it moves on to how people shaped the landscape. Whether building roads, agriculture, or deforesting. Also how important the weather is to people in this country. Then there’s nature striking back, the forces were often incarnated and explained through ghosts and witches.

There’s a huge tradition of visionary and unhinged artists in this country. A lot of the greatest artists weren’t the most conventional, like William Blake. But there’s also people like Louis Wain with the cat picture, who ended up in the asylum. He did anthropomorphic cats that sold hundreds of thousands of copies, then suddenly he started having visions and drawing these terrifying psychedelic visuals of cats.

TM: There’s one great picture in the book of the cow jumping over the moon in the book by Paula Rego …

SE: Oh yes. Things like nursery rhymes and fairy tales are really scary, so dark. They are in every culture, but here it just permeates everything. Take scarecrows, again other countries have them, but British scarecrows, they are terrifying!

TM: We do have a rich history of folklore. For a very small island we’re seriously steeped in it …

SE: I think it may possibly be because people come from so many different places. There’s a great muddle of ancient Celtic stuff, then things brought in by the Saxons and Vikings. In the mythology of England there’s new characters being introduced with a more diverse population. So, you’re getting the folk tales of Southern Asia, or those of the Caribbean and Africa. They’re manifesting as part of the English psyche. I really wanted to include that. There are lots of black and asian artists working now who use religious iconography, but putting them in a British context, which is really fascinating I think.

One of my favourite juxtapositions in the book is towards the end where there’s a sculpture of a lion with mushrooms growing out of it. So it’s obviously the British Empire and a symbol of that, but then the page before that is the tiger by Chila Kumari Singh Burnam, a Liverpudlian artist whose stuff is based on her Indian background and uses these extraordinary patterns brought from eastern art and mandalas. So, the English lion might be there covered in mushrooms, but there’s lots of life yet. It’s not been replaced by the tiger, but there’s a new vitality in English culture.

TM: That was clearly a very conscious decision, that kind of juxtaposition throughout the book.

SE: Yes. I do spend a slightly unhinged amount of time on the juxtaposition of things. Ages. Fortunately the designer Josse was fantastic. He got it instantly. There is a story element to England on Fire. It’s important the images go together.

TM: Many of the images clearly have an esoteric meaning behind them – are you someone who looks into decoding those things?

SE: I am. I wouldn’t say I’m an expert. But I am fascinated by magical and alchemical imagery. That’s a rich vein of inspiration. There’s a really odd tradition of English magic and alchemy which goes back to the invention of modern witchcraft. Modern witchcraft essentially came from a cellar by The British Museum in what is now The Atlantis Occult bookshop.

Basically all the rules of witchcraft were invented in there about a hundred years ago. It’s a bit like The Royal Family. Everyone thinks these are ancient rituals, but The Royal Family reinvented themselves after the First World War. And with modern witchcraft that came out of a basement at around the same time.

TM: Is there a particular area in England on Fire that represents your main interests?

SE: I am really interested in the pictures of supernatural events in general. I’m fascinated with stone circles, there’s a lot of that in the book. Things around folklore. I’d love to do a book based on the collection of The Museum of Rural Life. It’s a place near the University of Reading that has the most bizarre stuff. I think it explains quite a lot about the psychology of English people, English rather than British.

The English are obsessed with the world behind the real world. I’m quite fascinated by why in Victorian era there was this huge Vogue for fairy paintings. Victorian fairy painting is really weird. Some of the people involved like Arthur Conan Doyle’s father, Charles Altamont Doyle, who I didn’t include because he’s Scottish, was the most extraordinary character. He ended up in an asylum. The Cottingley Fairy photographs, which Conan Doyle was convinced by, were amazing in how they essentially conned a nation. People wanted to believe in them. I think it was partly due to the trauma after WW1, they wanted something to believe in.

One of my favourite modern artists who embodies this and does it in a really clever way is George Shaw. There’s a couple of things by him in the book. Most of his paintings are based around the estate he grew up in Coventry. So a 40s/50s council housing estate. He paints using Humbrol model paint because when he was a child he was embarrassed about wanting to be an artist. So, what was acceptable was for him to go and buy Humbrol paint, as it was to do Airfix models.

He still uses that as it was what he first started painting with. It gives all his paintings a weird spin. They’re of the wastelands and playgrounds of Coventry. These are the most humble places, suffering from austerity. Some of the paintings are like William Blake’s. I doubt he’s religious, but they’re visually intense. That kind of tradition of artists like Blake or Turner who would have these luminous landscapes with angels and gods, that continues with a lot of modern art.

TM: Tell us a bit about the words Mat wrote for the book. How did that all come about?

SE: I didn’t know Mat previously. It was very fortuitous, he was recommended by the publisher. I was adamant that I didn’t want to do the text. Partly because I was committed to other things and I thought this was just picture research. The other publisher, Repeater books, who published Mat’s novel The Ruin, their editor Fiona suggested Mat as someone who’d be really good to do the words. I had some conversations with him and realised he was perfect for it. He got what England on Fire was about and we had lots of long phone conversations about things. I’m thrilled with his text. It’s the perfect compliment for the images.

TM: We’re currently living through interesting times – do you see this being reflected in contemporary English art?

SE: I do, definitely. I will say that I think that some of the major institutions have changed quite a lot in the past couple of years. Certainly places like Tate. There had been a lot of complaints about colonialism and whether Tate should rename itself. Certain major galleries are responding really well and I think Tate are doing a fantastic job at the moment. Some of the shows they’ve had on in the last year or so are great. The new installation in Tate Britain by Hew Locke called The Procession about Caribbean carnival is the most incredible thing. I’m not sure they would have commissioned that ten years ago.

Things have changed so much that people have to resort to guerrilla tactics because you can’t go to art school unless your rich. And you can’t get grants, or there’s limited places. A lot of major arts schools are full of students with parents who can give them financial security. So, the kids from different backgrounds are having to create their own environment. Their own network of galleries, fanzines and blogs. There’s some incredible stuff that comes out of that.

TM: What do you hope people take from the book? I guess one reason must be bringing some of these images to the fore and also keeping them alive …

SE: Definitely, yes. There were things that surprised me that we came across. It was serendipity with some of the images we found, many weren’t in display in galleries anywhere, so there’s nowhere else to see them. It was about looking beyond the obvious stuff people have been spoon fed and also to introduce new artists that people may not have been aware of.

TM: Is there a lesson you’ve learned from your time collecting and curating images?

SE: From being with artists and publishers, I will say bigger is not always best and small is not necessarily beautiful.

England on Fire by Stephen Ellcock and Mat Osman, published by Watkins is out May 10th, 2022

Click the banner to share on Facebook