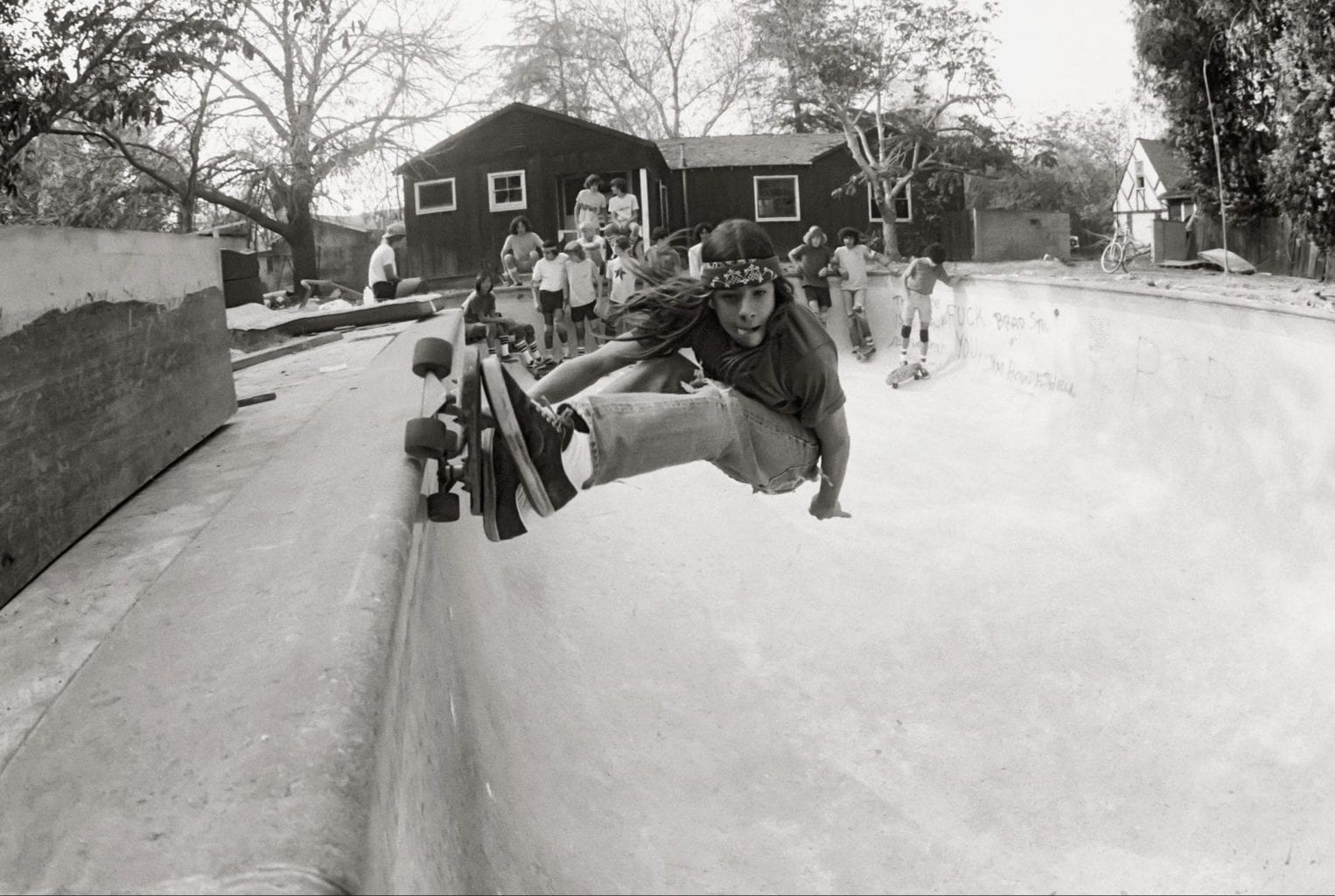

It was 1975 when Hugh Holland first noticed the beginnings of the burgeoning skate in Southern California. At the time his photography hobby was developing into something more serious, and once he’d witnessed the surf style grace of these figures on their boards, who he’d go on to document constantly for the next three years, he knew he’d found his subject.

Hugh began to hang out with the kids who were blazing a trail on this new scene, capturing them defying gravity as they pushed boundaries, whether ripping up pools that were empty because of the drought at the time or down at the skate comps popping up all over the region. Hugh shot skaters that went on to become legends in the sport, such as Stacy Peralta, Jay Adams and other members of the renowned Z-Boys team from Santa Monica and Venice. His seminal images show off this golden era like no others and paved the way for other great skate photographers who followed in Holland’s wake.

With the recent release of his new book, Silver Skate Seventies, which showcases some of his fine black and white images from the time, we caught up with Hugh in Los Angeles to talk about those hazy seventies days, what it was like being part of such an exciting movement and how photographers dreaming of having their own gallery show can one day achieve just that by following his top tip.

The MALESTROM: Tell us about your start in skate photography. How did it all come about?

Hugh Holland: Well it was 1975. I first noticed them right on the street. I was in the middle of LA working, I had a shop of my own which I’d just recently started and I had a workshop where I did furniture finishing. They were on the streets everywhere, just everywhere. At the time I wasn’t thinking much about it apart from that it was something unusual. But the first time I really started taking pictures was when I saw them doing vertical for the first time in Laurel Canyon.

I saw them in a drainage bowl in the Hollywood hills going up and coming down and I thought that looks really interesting. So I found a place to park, walked over there with my camera and that was the start of it. From then on for thirty years I didn’t stop taking pictures in my time off. It was a phenomenon at the time and I didn’t even realise how much. I don’t think anyone did, it was just happening.

TM: So you didn’t feel like you were part of a movement at the time necessarily?

HH: I just knew I wanted to photograph it. I’d been taking pictures for a while and had a darkroom at home and I was shooting everything and anything that came in front of my lens and when I saw the kids skating I thought this is my subject. I was in the right place when it was all happening and I had a lot of fun documenting it (laughs).

TM: And you were essentially learning as you went on, experimenting and developing your own style?

HH: Yes, that was the whole thing. It was a learning experience for me in photography. And boy did I learn right there on the spot. I learned how to compose in the camera in that split second. And I didn’t just do action, it was the whole atmosphere that was part of it. I was documenting really.

TM: Was it a conscious decision to shoot in colour?

HH: Yes it was. I remember thinking as soon as I began shooting the skateboarders this will look good in colour. I was shooting mainly in afternoons and the smog in the air sort of gave everything a warm glow. I did still shoot in black and white, but I have a lot more pictures that I took in colour. The colour seemed more appropriate with it being Southern California and the look of those long afternoons.

I noticed the difference was I was shooting black and white for more snapshot, fun type pictures, whereas I was shooting colour when I was thinking these shots could end up on a magazine cover. I was using Eastman Kodak colour movie film, which also had a warm glow to it. This photo lab nearby sold it and it was cheaper than Kodachrome and Ektachrome. I would use them for the really special shots, but now, I think that the shots I took on colour movie film are actually nicer.

TM: What were people’s attitudes towards the skaters at the time?

HH: I know that at the beaches signs started to go up saying ‘No Skateboarding‘. But in the street people didn’t seem to notice it that much as first, although they started to after a while. 1975 was kind of a breakthrough year, these were just kids going for it. Most of them were surfers, but they might live a long ride from the beach so they took to the streets and then to the hills.

Then after the hills, they went to the drainage ditches, or storm drains, cause it never rained that often then of course, so they tended to be dry. Sometimes the skaters would have to go and sweep up all the dirt from the bottom so they could ride on it, that happened a lot. Then right after that, the swimming pools started to become empty because of the drought in Southern California and everyone rode in the swimming pools.

That was a big event, I would be up there shooting in the storm drain and someone would turn up and say, “there’s an empty pool on the other side of town.” I don’t know how they knew, this was before cell phones and the internet, but somehow the word got around fast. I think back on it and wonder how it happened. I had a car so I was always giving a bunch of them rides to another location. It was fun.

TM: You were taking pictures of the Z-Boys from Dogtown, and the likes of Stacey Peralta, a legend in the sport. It must have been a great thing to be a part of?

HH: Yes, it was. There’s one picture in my new black and white book of photos from a big national contest in ’75 at the Del Mar Racetrack in San Diego. I was shooting this crowd of skaters who were just sitting there waiting their turn to skate and there are the Dogtown boys right there, kinda out of sight, some in the front, some in the back. I wasn’t even focussing on them specifically, I was shooting the whole crowd.

That made me think and remember how that was, that they didn’t seem too special at that time, although everyone was talking about them at the contest. But that was the first time the Dogtown crew really got exposed to the San Diego/Orange County Southern faction. That was the first time they came out. It was a time when all of the skaters were mixing from all over California.

TM: Did you socialise with them all? were you going to parties?

HH: Yeah, I hung out with them a lot. Mostly just when they were skating, with me taking pictures. I was welcomed right from the start by these guys. I had a camera and not many people had one in those days, not like now. But back then I was a cameraman. I remember Jay Adams would say, “Hey cameraman. Get this!” Then he’d do a trick and he’d be like, “did you get it?” (Laughs). They were anxious to show off cause it was all new. They were so excited to be hitting new highs, getting air for the first time. All that stuff was cool. I was having fun, they were having fun.

As I said, I had a car and someone always needed a ride, so I ended up going across the whole of California, all kinds of places. Now with the book being out and the internet, I’m meeting these guys again. I was out of touch with a lot of them and now we’re back in touch which is great. We had a book launch at the gallery the other day and there were about six skaters there who are in the book. Half of them I didn’t really know until the other night, which was exciting for me and them too.

TM: Why did you stop photographing that scene? Was it just time to move on?

HH: It was that partly and it was also because the skateboarding itself just changed rapidly. It was the whole look of it. I used to like photographing the skaters who were running around shoeless and shirtless, with their long hair and the look and the style that they had. They were applying a surfing style to skateboarding. It was the style that attracted me and the wild abandon of it all. That for me was the photogenic thing.

When they started wearing uniforms and helmets and kneepads and shoes, wearing logos on their chests, it just wasn’t that interesting to me anymore. I’m not interested in sports photography really. I prefer taking atmospheric shots and documenting an era, showing what happened. So I just gradually stopped doing it and moved on to photographing other things. And that’s why.

TM: You must be proud because what you did capture were era-defining pictures that are still replicated to this day that had an impact on popular culture. It must have been great to be at the forefront of that?

HH: Oh yes, very much so. I’ve done a lot of photography, I started out a couple of years before the skate thing, so early 70s. And it was the skateboarding that really pushed me to do a good job. That was where I learned everything. Decades later I’m still photographing everything that comes in front of me, I think of myself very much as a street photographer. So far I don’t have another series of photos that had the impact that those pictures had.

When the pictures came out first about fifteen years ago and they were made public, because they sat in a box for thirty years where no one saw them, after that people put me in a box as a skate photographer. I said to my gallerist, “I don’t want to always be known as a skateboard photographer for the rest of my life.” He said, “well you should be proud, cause you were the best.” (Laughs) No, I am proud, I really am.

Some young photographers say to me, “how do you get to have a book and gallery shows?” I always say, “if you have a good series of pictures, just wait thirty years!” That’s what I did.

Silver. Skate. Seventies. (Limited Edition) Photographs by Hugh Holland (Chronicle Chroma, £250.00) available now.

Click the banner to share on Facebook