In the Northern Hemisphere December 21st marks the winter solstice. A special day in many ways. Not least that it signals the low point of the sun, the longest night of the year, and thanks to the earth’s axial tilt, the night when days will grow longer and darkness diminish. Symbolically, this day represents the time of new beginnings, the death and rebirth of the Sun, light triumphing over darkness, all heralding the promise of renewed life.

In times gone by it was a hugely significant time in the calendar for dwellers on this planet, yet this significance has dwindled for the vast majority of us, with the reasons why these yearly markers were such a big deal in the past largely beyond our comprehension.

Many ancient monuments around the world are aligned with the sunrise or sunset on the winter solstice. Places where festivals and rituals would take place to celebrate and honour this solar cycle.

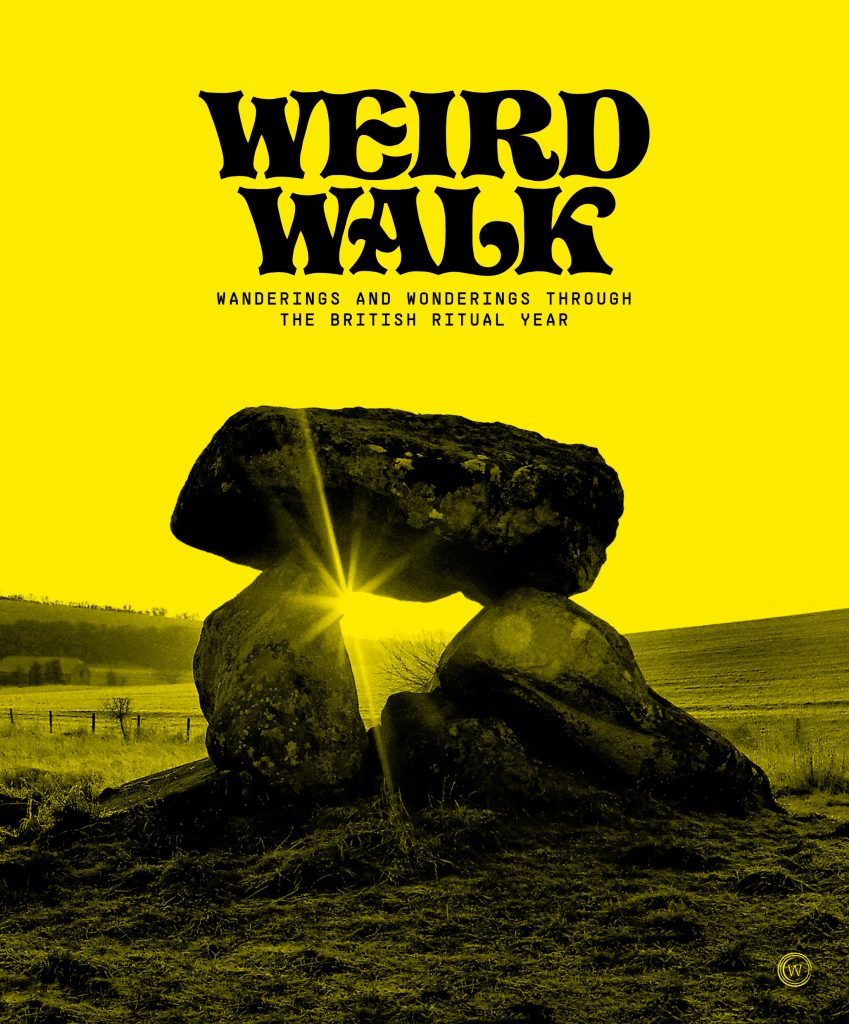

To get some enlightenment on this fascinating subject we turned to the writers of iconic zine Weird Walk. Their fantastic new book, Weird Walk: Wanderings and Wonderings Through the British Ritual Year, acts as a guide to Britain’s strange and ancient places, looking at how the seasonal patterns connected us to the land. Here they tell us about Stonehenge’s place within the cycle and it’s relevance to the winter solstice.

“Although strongly associated with the summer solstice today, it is likely that Stonehenge was a place of winter, a shrine to the ancestors that was at its peak in the coldest season”

There was once a circle of stones on the island of Ireland known as the Giants’ Dance. For millennia it stood atop the mountain Killaraus, having been brought to this spot by titanic folk from the shores of distant Africa.

In the words of the wizard Merlin, these were “mystical stones and of a medicinal virtue”. Merlin stated that the African giants who set down the megaliths would use them to cure ailments by bathing in water that had washed the stones. When special herbs were added to the enchanted liquid, battle wounds would miraculously close.

Merlin told the tale of the Giants’ Dance to the British king Aurelius Ambrosius, who was eager to erect a monument to the Britons who had fallen fighting off Saxon invaders.

And it was Merlin who suggested that the circle could be transported across the Irish Sea: “They are stones of a vast magnitude and wonderful quality; and if they can be placed here, as they are there, round this spot of ground, they will stand forever,” he announced prophetically.

The king was convinced and resolved to have them taken from the Irish. Through a mix of brute force and magical artistry, the feat was accomplished, and the Giants’ Dance was reassembled upon Salisbury Plain.

So runs the earliest account of the foundation of Stonehenge in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s twelfth-century epic History of the Kings of Britain, and, for many years, it was the dominant theory as to the great monument’s origin and purpose. As other explanations developed, involving everyone from the Druids to the Ancient Greeks, it seemed unlikely that Merlin would get a second hearing.

If Stonehenge is anything, however, it is open to interpretation, and some 900 years after Geoffrey’s description, scholars have once again turned west for the site’s origin story. In an echo of the Merlin legend, the visionary archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson proposed that the bluestones of Stonehenge (sourced from the Preseli Hills of Pembrokeshire, Wales) were first erected as a local stone circle before being disassembled and transported to Wiltshire.

Part of the A303’s favourite Neolithic temple was second-hand, pre-loved by earlier worshippers. The proposed site for this proto-Stonehenge is Waun Mawn, the remains of an unfinished circle in the Preseli Hills, not far from where the bluestones were quarried.

Although recent excavations have shown that the monument couldn’t have held all of Stonehenge’s bluestones, there are similarities with the Wiltshire super complex: the diameter of Waun Mawn was 110m(120yd), exactly the same as Stonehenge’s enclosing ditch, and it is also aligned to the solstice.

Debate will continue over Parker Pearson’s disassembling theory, but it is a powerful and poetic idea with a clear message for the present. For unlike Merlin’s triumph over the Irish, the dismantling and re-erection of the stone circle can be seen as a unifying act: Neolithic migrants from Wales took down their cherished stone circle and delivered it to an already holy landscape.

Imagine the cooperation this would have taken; imagine how special these particular stones must have been. As the archaeologist writes, “Bluestones were brought to the land of sarsen stones and installed at a sacred axis mundi, where the sky and the earth were envisioned in cosmic harmony, and where people of different cultural and regional origins might gather for collective monument-building and feasting.”

Today, Waun Mawn is an evocative and spectral remnant of a stone circle. When you climb up from the road below, the site’s lone standing stone reveals itself first, while other megaliths lie recumbent in the vicinity.

It is a desolate yet beguiling location, the Preseli Hills providing a majestic moorland amphitheatre for whatever rites were once observed here.

Although strongly associated with the summer solstice today, it is likely that Stonehenge was a place of winter, a shrine to the ancestors that was at its peak in the coldest season, the period when death is most vividly drawn.

The nearby Durrington Walls complex was the site of a midwinter feast that could have brought people from as far away as Scotland. Analysis of animal remains has shown that folk descended on the area from across Britain at this time.

Mike Parker Pearson and his colleague Ramilisonina have suggested that the monument builders used timber to symbolise the living and stone the dead.

A visit to Waun Mawn, Craig Rhos-y-felin or West Woods allows us to hear an echo of Stonehenge its infancy, and to connect with its potential as a place for unification.

We like to imagine that the Merlin myth carries the faint charge of memory – of stones from the west brought to the most sacred spot of them all, where people from across Britain could come together.

Through feasting, building and remembering those who had passed over, disparate communities bonded for a midwinter festival, resolved differences and looked ahead to warmer days. This spirit of unification, of celebration in a storied landscape, feels well overdue for a wider revival.

Weird Walk: Wanderings and Wonderings Through the British Ritual Year, published by Watkins, is out to buy now.

Click the banner to share on Facebook