In the world of mountaineering and rock climbing Allen Steck, it is safe to say, is a living legend. Having conquered Mount Maclure at the age of 16 in 1942, he went on to become a true pioneer of the sport, putting many of the most challenging climbs known to man on the map – literally!

Alongside his great friend John Salathé they forged the first route up the north face of Sentinel Rock in 1950, an ascent that to this day bears their name, before overcoming the south face of Clyde Minaret in the Sierra Nevada in 1963 and scaling Hummingbird Ridge on Canada’s Mount Logan for the very first time in 1965.

Tragedy and death have struck on more than one occasion and he himself has been buried alive twice by an avalanche in a career that spanned almost eight decades. With so many extraordinary experiences and accolades to his name, it seems only fitting that he’s put pen to paper for the release of his memoir, A Mountaineer’s life. At 91 and showing no signs of slowing down, Allen Steck joined The MALESTROM to talk about his incredible life lived to the extreme.

The MALESTROM: Allen, it’s an honour. So tell us, when did it all begin?

Allen Steck: I did my very first climb with my brother when I was 16, which was in 1942. We were climbing in the High Sierra, Yosemite and we were climbing near Mount Maclure and I said to my brother, ‘Let’s climb this. It looks pretty easy’. And that’s how it happened. Then we got caught up in World War II. I was in the South Pacific on a destroyer escort in the latter part of the war and I got out when I was 20 years old, and I started climbing again then.

TM: You then joined the rock climbing division of the Sierra Club, an environmental organisation in California?

AS: Yes, they did a lot of kayaking and hiking and so forth and because a lot of rock climbers helped start it, there was a rock climbing arm and I got affiliated with them.

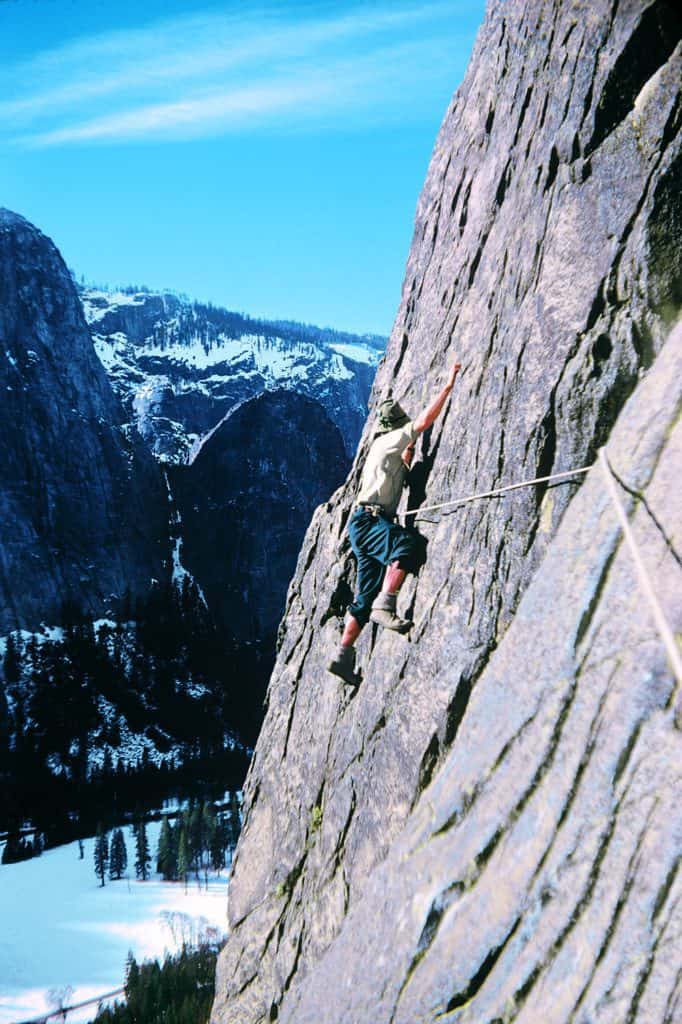

TM: You started climbing sheer faces in Yosemite National Park in about 1947 before equipment had even really been developed. I believe even pitons (metal spikes driven into cracks) were in their infancy?

AS: That’s right. People about 10 years before me were using big heavy nails to climb with. They were hammering nails into cracks and climbing using the basics, but when I began we started using pitons from Germany and then later from Italy too.

TM: Those were very early days of rock climbing. Do you remember being fearful back then?

AS: No, I was never afraid of heights. You start out being a little afraid, but once you get used to climbing, you tend to block out the fear, as long as you’re in control of the climbing.

TM: So, on the sheer faces, you never worried about the heights?

AS: I just don’t think about it… it doesn’t bother me.

TM: One of the early seminal moments in your rock climbing career was when you travelled to the Alps to climb the Dolomites in 1949 with Karl Lugmayer, who became your lifelong friend…

AS: Yes, I was studying in Switzerland not long after I got out of the war in about 1948-49, to study German and Russian, and I got this letter from a guy in Vienna called Karl Lugmayer which said he had been corresponding with people in the Sierra Club and was wondering what climbing was like in California.

They told him that I was in Switzerland and that they should get in touch with me, and that’s how we got together. I took the train into Vienna when it was still partitioned into four quadrants: the Russians had theirs and the Americans and the French and the English. We met; we liked each other and decided to climb together.

MS: Some of the climbs look daunting, especially the Vajolet Towers, one of the most famous rock formations in The Dolomites?

AS: Well, we climbed all season and by the time I got to the Vajolet Towers I was in good shape, as we’d done a lot of climbing in Austria beforehand. We climbed in a place called Fleischner and did several very hard and dicey routes. I was young back then too and I was in really good shape and by the time we got to the Vajolet Towers, it was easy.

TM: Easy? They don’t look easy! They were even featured in the opening of the Sylvester Stallone film, Cliffhanger. It sounds like you had an immediate bond with Karl back then though?

AS: Yes, yes. We were the same age, about 24 I think and we had the same desires in climbing and we got on well together.

TM: And what’s remarkable is that from that first climbing expedition together in 1949, you stayed friends for the rest of your lives, and even spent your 80th birthdays together?

AS: That’s correct, he came over here to the USA for my birthday.

TM: And you even named your children after each other?

AS: Yeah, I named my son Karl and he named his son Allen. Funnily enough, I just had a chat with his son about half an hour ago as he called me from Austria, thanking me for sending him the book I’ve just written, ‘A Mountaineers Life – Allen Steck’.

TM: That’s extraordinary, to have a friendship like that which has been forged from mountaineering nearly 70 years ago.

AS: Yep. It’s changed my life, yeah. I became addicted to it you might say.

TM: You’ve been a mountaineer and rock climber your entire life. Do you think it’s contributed to you having lived such a long and healthy life?

AS: You know, it probably did, because my heart was used to heavy, heavy exercise for many years, so I guess I’ve got a pretty strong heart (laughs), let’s hope it stays that way!

TM: It must be all the fresh air and adrenaline?

AS: Yeah, could be, right! I also think because I have a good healthy dose of red wine every day as well (laughs), and I think that’s helped too!

TM: When you climbed the 1500ft north face of Sentinel Rock in Yosemite National Park in 1950, you said it was one of your hardest ever climbs?

AS: The north face of Sentinel is right above climbers camp 4, and you look up and see that wall and you think, ‘There’s just got to be a route up there!’ Up until then though there was still no route on the north face of Sentinel.

That’s how I got attracted to it and I made several attempts and the climbing was pretty fierce, a lot of chimneying and so forth, and it took a couple of years to get to know that. Then, 1950 came and I got a hold of John Salathé (a pioneer rock climber who invented the modern piton) and we did it in four and half days.

TM: Was there any moment on such a tough climb when you thought about giving up?

AS: Well, by the time me and Salathé attempted the route, we already had half of it wired, but when we got to the upper chimneys, higher up, there was little chance of retreat. It was very hard, so the only way was to go up and finish the climb by continuing.

TM: That ascent is still named the Steck-Salathé route today. Are there certain attributes you look for in a climbing companion?

AS: Oh, that’s a good question. There are some climbers that you feel comfortable climbing with. A climber called Fred Beckey (another pioneer who made more first ascents than any other North American), who asked me to climb with him, but for some reason, I felt that I didn’t want to get involved with him.

TM: That’s interesting! Why?

AS: Yeah, he was a very controversial character, so I didn’t climb with him. But I think most people I climbed with I had a good relationship with. I think one of the best examples were the climbers I did the Hummingbird Ridge with (the south ridge of Mount Logan, Yukon, USA), Dick Long, Jim Wilson, John Evans, Frank Coale and Paul Bacon. We worked so well together as a team that it helped us make that ascent.

TM: That was in 1965 and it sounded truly epic, it still hasn’t been repeated to this day, is that right?

AS: That is correct. The route we took has not been repeated today and the reason is that most people want to climb Alpine style; they don’t plan multiple camps. We had multiple camps and we always moved, but we only had one camp, so we moved camp ten times.

I know that one group tried to do it Alpine style and they got hopelessly screwed up. Also, we started on the rocky section of the Hummingbird Ridge and that took forever to get through 4000 feet of the rocky area.

TM: How long did it take?

AS: The whole thing took 35 days. Luckily we had enough food, although we were on rations for part of the time because we were afraid of running out.

TM: Do you lose a lot of your body weight when you’re on rations and climbing like that though?

AS: Yeah, about 15lbs each. But we didn’t suffer from that on the climb and we managed to deal with that okay, but we were hungry all the time.

TM: Your Hummingbird Ridge climb is now ingrained in mountaineering folklore. It takes a lot of determination to succeed in something like that?

AS: Well, I gave a talk in London once about it at the Alpine club and a guy came up after I finished my lecture and handed me a card and told me, ‘the one thing that enabled you to do that climb is that you persevered.’ We did persevere, we just kept moving at every opportunity. If we had a chance to go up, we took it, and that’s how we got to the top. The card he handed me said,

“Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not; the world is full of uneducated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent’.” – Calvin Coolidge.

TM: Why is that ascent so arduous?

AS: Well, we started at around 5,500ft and in the end, you’re at almost 20,000ft, so it’s a long elevation gain to make, and not only that, the ridge is six miles long. We started at about three and a half miles out, and the summit was three and a half miles away, horizontally.

TM: It’s considered one of the most challenging in mountaineering history…

AS: Yes, I believe it is. Someone once said it was the most difficult route ever accomplished, but that’s because most people like to do everything Alpine style and carry everything with you, not where you haul loads as we did.

When we started the Hummingbird we had 16 loads, so while two people were leading, four people had to take trips back down so they could fetch a load. I think if you’re Alpine style and you’re carrying 50lbs, I think they say you’re not able to go more than eight or ten days.

You run out of food, so how are you going to do a route of that magnitude? You’re not. That’s one of the reasons that it still hasn’t been climbed today.

TM: When you look back now at the achievement of the Hummingbird Ridge, do you look back with a sense of satisfaction or do you look back and think you could have climbed it differently?

AS: You just look back with satisfaction and think, ‘My God, look at what we did.’ And we planned well, you know. When we got to the top of Mount Logan we still had enough food left in case we got into a six to eight-day storm. People often get up to the top of Mount Logan and they don’t have those reserves; we did!

TM: There’s such a risk involved in mountaineering, the first time a member of your team died, it was from altitude sickness in 1952? Did that not put you off?

AS: Well, its one of the chapters in my book called, ‘Is climbing worth dying for?’ And obviously I came to the conclusion that it was. When Oscar Cook died during our expedition in Peru, it didn’t deter us from continuing.

Once we got him down, his body that is, and got him out to where he could be taken to Lima, we then went back and had four or five more days climbing there. It was a very sad thing, but that’s what happens occasionally in mountaineering.

TM: You’ve said that as life-affirming as climbing is, the possibility of death, not the wish for it, is part of the complex web of motivation for extreme mountaineering?

AS: Well, yeah, right! And you can read that in the book. I’ve also been buried two times in an avalanche. Now, you would have thought that would have stopped me going back into the mountains but it didn’t, I kept on going.

TM: What does it feel like being buried by an avalanche?

AS: Well, it’s pretty grim I tell you that! One of the avalanches was at the Soviet mountaineering gathering in 1976, I think. The avalanche was started by an earthquake and I was caught in the avalanche and when it got me I just had to swim, and swimming is just a natural thing that you do, because you know the more that you thrash about, the more close to the surface it will keep you. When the avalanche eventually stopped, at least my head and hands were out of the ice.

TM: Do you mean trying to swim as you’re being dragged down the side of the mountain by the snow?

AS: Well, yeah. You thrash actually; you’re not really swimming. You’re just thrashing to try and keep yourself as high up as possible.

TM: Is that a known method for survival in an avalanche?

AS: You must always swim.

TM: What about the other time? Did you ever think you wouldn’t get out?

AS: Oh, I died immediately when I was caught in that one. I had about 16 minutes to live when some people came along and dug us all out. So, I was very lucky.

TM: Wow! Incredible. Now the climbing expedition in the Pamirs in Russia in 1964 when the party of eight women died? That sounded truly tragic.

AS: That’s right, it was tragic! Terribly tragic and it was so unnecessary. The group of Russian mountaineering women up ahead were told to come down by the Russian support team, to get off the mountain because a big storm was coming, possibly the worst they’d seen in years, and they didn’t come down.

They had a chance to live if they’d just followed his advice for God’s sake. You should read the whole episode in the book. He said to everyone on the radios, ‘Get off the mountain.’ We didn’t because our radios weren’t working and we had no idea that this storm was coming in, but we were further down, they were on the summit.

TM: It must have shaken you though, witnessing that?

AS: Oh God… can you imagine laying there in your tent, crying at 7400m. That doesn’t happen very often. That storm must have blown about 100mph and we went to bed in all our gear so if we lost the tent, we’d have a better chance of surviving.

I remember I woke up at one point in the night and I saw static electricity discharge from the tent fabric to the tent pole. I don’t think that happens very often.

TM: You were one of the first to find their bodies as well?

AS: Yeah, yeah… That’s right.

TM: Allen, you’ve certainly seen some things in your life. It’s almost like you’ve lived about a hundred lives?

AS: I think so too (laughs). And now I don’t have to do it anymore, thank God!

TM: Well, you survived, you’re healthy and you’re still laughing?

AS: Yeah, right! (laughs)

TM: When you filmed your climb of El Capitan in Yosemite with John Salathé in 1966, was that the first or one of the first mountaineering films ever made?

AS: I think so, and I think it’s also the first film ever made in Yosemite by the climbing members and not by a cameraman or crew, like the first films that were made. It was also the first time that the route had been done in four years and we didn’t take any bolts, so it would have been very hard to retreat with just pitons.

TM: And when climbing a sheer rock face like El Capitan, did you sleep on the side of the cliff?

AS: Well, we had no Port-a-ledges, they hadn’t been invented. We just laid out on the rock and slept.

TM: What, just hanging there in the ropes?

AS: Yeah, we just hung in the ropes and slept. We didn’t have sleeping bags and so forth, we just toughed it out.

TM: That’s extraordinary. So, mountaineers and rock climbers have it easy now really?

AS: Oh what! They put vast camps up there and they don’t have to worry about anything, even the rain.

TM: Was it ever difficult sleeping, just hanging there on a rope?

AS: We were pretty exhausted so we had no trouble sleeping, let me tell you that.

TM: When you reached the top was it euphoric? And is that feeling addictive?

AS: Well, we were hallucinating when we reached the summit. When we were on the top and looking for the descent route, we had to stop and sit down because we were hallucinating because we were so drained of energy. I don’t think it’s that euphoria that’s addictive; I think it’s the sheer joy of climbing that’s addictive.

TM: You also had an integral part in the launch of the rock climbing magazine, Ascent?

AS: Yeah, well the Sierra club was publishing the rock climbing news in bulletins and I got to thinking that we needed a mountaineering publication of our own.

We started it in the ’60s and it became a very influential publication in the U.S and internationally, and it ran for about fourteen years. We published stuff that had never been published before, that even the American Alpine club didn’t publish.

TM: Do you think you’ve found peace within yourself by spending all those years risking your life?

AS: Well, yeah I guess. I never really thought of it that way, but I am very happy. I’m 91 now and still thoroughly enjoying life and I’m glad I don’t have to climb anymore (laughs). I never really thought that I was risking my life, even though I did.

TM: Finally, do you have any words of wisdom for our readers?

AS: I think if you’re a young person starting out you need to gather the experience you need and if you have any big ambitions make sure you’re prepared for them and do it slowly and do it the way that you get satisfaction from it. Also, perseverance will get you further than anything else.

To read more of Allen’s incredible stories buy your copy of A Mountaineer’s Life – Allen Steck: HERE

Click the banner to share on Facebook