If you had anyone draw up a list of the top five superpowers they’d love to have, it’s a fairly safe bet the power of flight would be pushing that number one spot in most cases. One British man has taken that childhood fantasy and through some seriously unique thinking and grassroots innovation, turned it into reality.

Richard Browning spent years tweaking and tinkering with existing tech with the heady goal of creating the world’s first jet-powered flying suit. After lots of ups and downs and plenty of bumps and bruises from using himself as the test dummy, the former Royal Marine reservist achieved what many saw as impossible, when he successfully took to the skies in his Daedalus suit, and soon after, Gravity Industries, his now multimillion-pound company was born.

Since then Richard has led hundreds of aerial displays around the world and has the exciting prospect of the Gravity race series ready to wow crowds. The iconic suit is also being used by the likes of the military and the Air Ambulance Service for very practical life-saving capabilities. Hollywood has even called to utilise the stylish super-suit in movies. Little wonder Richard has earned himself the nickname of the real-life Iron Man.

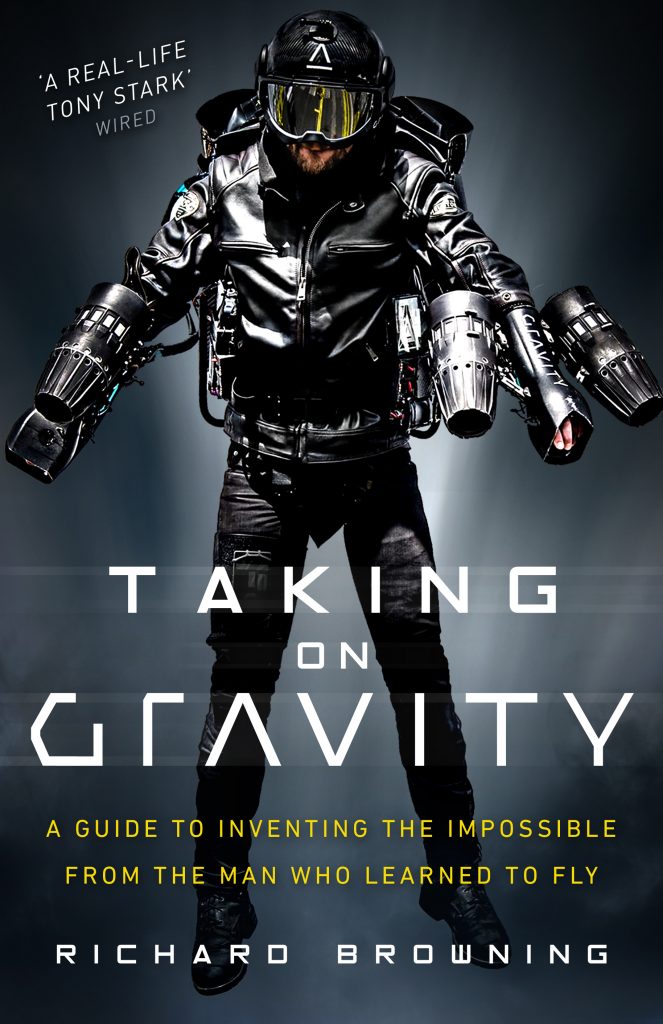

Hot off the heels of the release of his brilliant book, Taking on Gravity, which delves into the incredible journey that led to the realisation of the flight suit, we sat down with Richard to find out about his influences, the unconventional thinking that went into creating the suit and of course exactly what it’s like to soar around the skies like a real-life superhero.

The MALESTROM: Going back to the start of your journey with that initial concept for your flight suit. What gave you the confidence to realise this amazing idea?

Richard Browning: As with things that you’re not sure about, and I was certainly not sure about this at all, there was the process of prototyping, starting small and learning as I went along. It was also a case of not giving up my job and evolving and progressing it pretty quickly. That was the best kind of process to mitigate that.

I have this ethos that you can’t throw absolutely everything at an idea. Because innovative ideas tend to spend a lot of time doing things that don’t work. And if one of one of those failures takes you down mentally, financially, physically or whatever, then you can’t keep iterating.

So, I kept the journey as sustainable as I could, let’s put it that way. That included not giving up the day job. Which meant working on it in the evenings and weekends initially.

TM: You mention midway through the book about that special gene some have, certainly something your father seemed to possess. Do you feel that you inherited that as well?

RB: I think I’m very similar to how my father was. I think we’re both afflicted with this kind of passion to take on challenges. We see something and we dare imagine it being possible.

Maybe we think logically that it may not be possible and then just do it anyway. Frankly most of the time the sceptics are right, but every now and then when you do do something against your expectation, the excitement of that outweighs the disappointment of all the other fails.

TM: Your father seems to have been one of the major influences on your life and certainly in creating the suit. Would that be fair to say?

RB: Yes. I mean, I didn’t do it consciously in his memory or anything like that. But a huge part of the journey has been really related to my experience with him. I used to build and take things apart with him and his workshop. I lived his journey as to what he was trying to do with his business. Ultimately, he was taught a very harsh lesson in what happens when things don’t work out as you hope. But I never lost the passion for that same journey.

My pathway was to put in 16 years in a quite stressful but successful job with BP and put away enough money to allow me the freedom to go and explore a challenging journey like this, but without the pressure of having to pay the mortgage at the same time. It’s very much in tribute to him, but I say that in hindsight, because I didn’t have that in my mind when I started out.

TM: In terms of the actual building of the structure, one of the interesting things from the book is the fact you studied nature as a template for the wings …

RB: I’m by no means the first person to take inspiration from there. There are so many inspirations throughout nature. The process of evolution is an amazing mechanism to come up with solutions to problems. I wanted to try and take inspiration from that and not reinvent the wheel. Certainly at the start of the journey anyway.

TM: In terms of your own thinking. It comes up in the book that you maybe think in a slightly more unconventional way than others.Would you say that served you well with this particular project?

RB: Yeah, absolutely. You’ve got to be willing to imagine the unimaginable to embark down this journey. Very much. That’s the requirement of an entrepreneur, an inventor, or an innovator, to go against conventional wisdom. If you’re not, then you’re probably not really innovating, you’re just incrementally fettling an idea that you know to work.

I mean, there’s examples, like James Dyson messing around with a wood chip factory inspired cyclone system. He had a pretty damn good hunch it should work, but he was by no means 100% confident and had to go against conventional wisdom. Hoover and Electrolux thought he was mad and ignored him and weren’t interested, and look where he got to. Although saying that, at the beginning, sadly in life most of the time the sceptics are correct.

TM: You also mention in the book about childlike thinking for inspiration. Were there particular times and places where you came up with your thoughts and ideas? You write about getting up in the middle of night to run. Was that a time for innovative thinking?

RB: A lot of original ideas came about when I used to travel a lot with BP. I used to sit on aircraft, remember those days (laughs), and in that closed environment sitting on an aircraft, knowing I couldn’t really go anywhere for eight to ten hours, I would really enjoy disappearing into my own doors with a sketchbook and just kind of mulling over ideas and thinking through stuff.

Life is so busy for most of us most of the time, it’s actually quite rare to find quiet, closed thinking time like that. I really value those times. But also with running. As I said in the book, running is a great way of calming the brain and a great way of letting other stuff out.

There’s quite a lot of science now about what’s actually going on when you do that. It is the real brain chemistry of calming the noise and I love that also. That was a big part of it.

TM: With the building of the suit, the philosophy seemed to be about utilising and adapting existing tech. You used that in really clever and thrift thrifty ways. You term it as the magpie spirit …

RB: I was very much minded to try and make use of what was already out there. So, I would use these child baby carrier rucksacks as the structure to hold the static equipment. That was a great way of repurposing existing equipment, and that really accelerated our progress.

You’re not spending weeks trying to recreate what somebody else has already done really elegantly, you’re getting on with your bits, which is how to potentially position those engines in the right place rather than engineer a new backpack.

TM. In terms of the major barriers, obviously, there were lots of different hurdles along the way, but what were the toughest moments?

RB: It’s one thing to have the idea, it’s another thing to go out and take the plunge and buy by an engine. That was quite a breakthrough though, because it turned out to work much better. The thrust was quite benign, it was quite a controllable thing. All pretty good.

It was very frustrating trying to work out where to fix the power and just when you thought you got it right, you’d have an engine break or the system failed in some way and then you spent more time trying to fix it and get it back right again, and then you weren’t doing the testing. So your imagination always runs ahead of where your progress has actually got to.

TM: You mentioned the testing there. In the book you mention the different farmer’s fields being burnt when used as test sites. It must have felt quite exhilarating to see those small bits of progress with the suit.

RB: Oh, yeah. You live for that progress. They’re the things that keep you going really. If you don’t get enough of them, then your enthusiasm will suffer. Life usually throws you just enough enthusiasm, just at the right time to keep you going. Although there’s no guidance, or signposts, or even certainty that the road even goes anywhere.

TM: I suppose the one question a lot of people would like to ask you is what was that first flight like? It must have been incredible?

RB: With that first flight it wasn’t just the physical action of doing, it’s what it represented. From that moment onwards, I knew. That was the beginning. It could progress and improve so much from there, but it sort of represented the eight or nine months of work up to that point, and then all the ideas for many months before that. It represented all of that, but it all came together and worked so spectacularly well. Yeah, it was amazing.

Even though I must have done thousands of these things now, every single time you do it, it is just a quite magical experience of just rising up and being completely free. It is like one of those dreams you have of flying, there’s no conscious thought about what to do. You’re entirely relaxed, and you just go go where you want. It’s amazing and it is kind of relaxing, it’s as intuitive as a bicycle in a weird kind of way.

TM: That’s one thing that struck me from the book, you wrote about the design itself, you consciously made it so you could control things by moving your arms rather than having a fixed pack. You wanted that strong human element to it’s control …

RB: Absolutely. There’s always temptation, especially in this day and age to automate everything and you gradually become a passenger. The original starting ethos was that I wanted to just add the minimal amount of technology, really just horsepower, and use the brain, which is an amazing balancing machine and your body is the flight structure.

You think about what’s going on in your head when you run across an uneven field for instance. That’s amazing that you can stay upright. So, I thought, let’s just reemploy this part of the brain to do a slightly different task and go from there.

TM: You mention about the importance of sort of failures, there was quite a few along the way, but what gave you that sort of persistence when a lot of people might have given up? What kept you going despite those setbacks?

RB: It’s just down to personality isn’t it. I was my own worst critic underneath everything. And yet, I still thought it would work. You get tested relentlessly and constantly challenged by yourself as to whether you’re really going to get there or not. But the dream, the enthusiasm, was for getting to that finish line and doing something against the odds. I think that’s the ultimate motivator.

TM: You seem to you seem to have been fairly lucky with injuries. You mention the odd bang and bruise, but have you have you ever encountered really hairy moments that you maybe would like to forget when flying?

RB: I’ve crashed a dozen times, but I’ve never done myself any permanent damage at all. I mean, that’s our ethos really. We just try to avoid doing anything that would ever do you any damage you can’t recover from.

So yeah, we’ll all have some bruises from screwing up every now and then. But then I used to cycle across London to commute every day. I like to think that I keep it less dangerous than that if possible.

TM: In terms of potential applications, the military seems to be one of the major ones…

RB: I mean, the military is just one aspect of what we do. But it’s a really quite fun one that helps us push the capability. It’s really interesting to see just how far we can take it. And it turns out we’ve got a real serious role to play in a lot of Special Forces operations.

TM: You’ve been called the real-life Iron man. Do you like that moniker? Obviously you didn’t set out to make an Ironman suit, but it must be quite a nice name to be called?

RB: I mean other people say that. We don’t say that. I guess it’s kind of flattering, because it’s a capability that’s make believe and not real, yet really quite potent.

Somebody in a really interesting marketing job once told me when we first launched, that the most elegant thing is that other people call you that rather than you try and run around saying you’re that. Because it’s not cool to say you’re that and it’s indeed not why I set this up. But it’s quite a flattering and quite fun parallel connection.

TM: In terms of the future, obviously, the race series was postponed, but what’s the current status of that?

RB: It’s just on pause really. I mean, we were three weeks away from getting on a plane to go and launch it and then Covid struck and we brought the shipping container back. Everybody’s had a pretty challenging time. We just shifted focus to a whole bunch of other activities. We’ve made a very successful fist of it. We’ve adapted as best we can.

The race series is ready to go when the world is ready for it. I mean, that in terms of gathering audiences and doing live spectacle stuff. I don’t sense that the world’s quite ready for that. But when it is, we’re ready to go.

TM: In terms of future innovations with the suit, obviously, I guess, you’re always tweaking and adapting, but is there anything else major that you’re sort of looking at, that you might be able to tell us about?

RB: All being well we’re going to launch and hopefully reveal the electric version at the Goodwood Festival of Speed in July. That’s going to be quite a moment. Slightly scary in that we keep telling people we’re going to do this and it’s one of those things where we’re ready now, but we think we can get there.

TM: I guess you’ll be taking on the flying duties for a while, you’re not gonna hang up the suit quite yet?

RB: My attitude is, with the tricky, gnarly stuff, I’m happier me doing it than I am giving it to one of my young folks and stressing about them doing it. I’m more keen. I go and accept what the risk is rather than somebody else.

Also, my two main engineers, they are also my best pilots. It’s worked out really well. The three of us can compare notes on how we feel about how something’s going. Rather than just handing it over to somebody else. It’s a bit like racing cars or motorbikes, there is a chance you can really hurt yourself if you’re not sensible. So, I prefer to take on that risk myself.

TM: We always sort of like to finish with some some words of wisdom. What’s been your main takeaway from the journey of making the rocket suit?

RB: There’s an important one for anyone trying to do anything new, whether it’s getting your arse off the couch to do a 5k run, set up a business, or go for a promotion, whatever it might be. I think innovation or doing anything new involves risk. And if you don’t take any risk, you don’t progress at all, full stop.

If you accept that and you’re going to take risks, the simple rule is just make failure of that. So in other words, risk is about things going wrong, if something goes wrong, when failure manifests, make it recoverable. That’s it. Make it financially, safety wise and reputationally recoverable.

If you can’t keep getting back up again, because you’ve pissed people off, hurt yourself or worse, or you’ve run out of money on that one idea, you’ve not made it recoverable. You’ve not noticed how innovation works, you’ve not gone and made the journey survivable.

Sadly I learned that very powerfully as a kid with my Dad’s journey. And I’m a bit of a guardian of trying to avoid making the same mistake or other people making the same mistakes. I think that’s the main thing I’d say.

Taking on Gravity by Richard Browning is out to buy now

Click the banner to share on Facebook