Many of us have fleeting dreams of swapping the hustle and bustle of city living for a new, perhaps simpler existence in a more rural setting. But few are brave enough to make such a huge change. Someone who did take that plunge in the most extreme way was writer and photographer Tamsin Calidas. Sixteen years ago she took the huge decision to swap a media career in London for a wreck of a croft in the Scottish Hebrides.

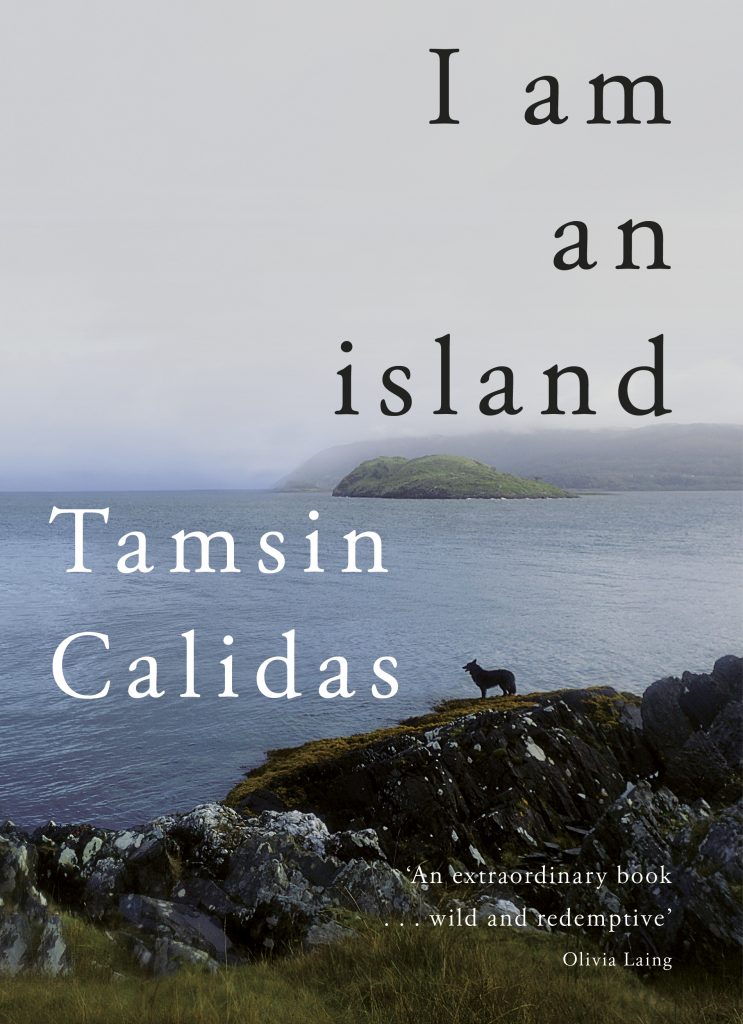

In her recently released and quite wonderful memoir I Am An Island, Tamsin recounts that big move to a small island with her then husband Rab. They immersed themselves in working the land and fixing up the croft to make it habitable, despite little experience in either area. What follows is a tale of difficult locals, marriage breakdown and other heart-wrenching tragedy. But also of survival and how a deep connection with nature can become life affirming and perhaps all many of us need to find true happiness.

We spoke with Tamsin about her experiences on the island, from having to cope with extreme solitude, to the incredible natural beauty of the Hebrides and the wild swimming that became such a transformative part of her everyday life.

The MALESTROM; Tell us what drove you to change your life to such a huge degree and get closer to nature with your move?

Tamsin Calidas: I guess it was twofold. The nature was always there, but my relationship to it and the solitude changed over time. There was that initial freedom from London – it felt anything was possible. It was the huge potential of the land and the croft, and the outstanding beauty of the landscape that inspired us. It was this that gave us the courage to take that first step to live, not just in Scotland, but on the island. It felt like an extraordinary gift.

At first, the very physical task of renovating the cottage and making it a home lay at the heart of our adventure. Immersing into the landscape was a natural adjunct – working the croft, and making it a viable concern, was all part of the work and our commitment. We had a lot to learn but we learnt quickly. These skills are crafts – the more you invest yourself into their daily practice, the more natural it becomes.

My challenges really started when Rab left to return back South. All my usual supports and structures sheared away dramatically one by one. In some ways, it is not dissimilar to this recent time of lock down. It’s an interesting link – many people will have shared a not dissimilar experience when unfortunately, all those things we rely on fall away, so you suddenly realise, they are not as stable as you thought.

In my life, at that time, everything collapsed one by one. I was grief stricken, struggling to cope; my father had only just very recently died; and my mother had been diagnosed with her terminal illness. For myself, I was shattered by the devastating loss of years of infertility. There was an unfinished house renovation and all the bills to pay. With the sudden departure of my husband back south, I was left to try and pick up the pieces.

I was unable to work and struggling to function as I had broken both of my hands, so simple tasks became overwhelmingly difficult. It’s unimaginable now. I was in this situation where your whole livelihood depends on your physical fitness and your ability to be self-sufficient. It’s one thing having people around, as neighbours or wider community, but it’s a different thing entirely when you’re out with family or very close connections to ever ask or expect the kind of support I was needing at that time.

I could not have coped without my dear friend Cristall. We were very close – a friendship built on a promise I’d made to her husband shortly before he died, to look after her. Friendship is a gift and you help each other. At that time, her presence was invaluable. She stepped in, in so many small ways, to help me. It was an amazingly intense time and for that I’m incredibly grateful. It offered one of those rare times in life when you can really explore friendship in its deepest way. She was like a mother to me, as well as my dearest kin.

Very sadly, this time did not last. Our friendship became part of that greater loss, that I write of in my book I Am An Island. It was the loss of Cristall that was the tipping point. I immersed deeply into nature. The wild offered me a deeper atavistic connection to nature. It gave me comfort, support and inspired over time an incredible strength. It felt that whatever I was feeling, the landscape and raw elements would always be greater – it felt big enough to carry the grief I was feeling. Over the years, it became my constant companion – like a loved partner that you strive to be with and to meet at all levels.

There was one night when I went out into the darkness and I really didn’t know what or who to turn to. That night I turned to the sky and stars. The stars in the Highlands are like nowhere else I know. It felt like the whole sky had descended. I looked up and I asked for help. And it felt like it took everything I had been holding. That was a turning point.

It was my first experience of quite how powerful nature can be. There were many more that followed. The real pivotal moment in the book is when I am standing on the shore and stepping out into the waves. The sea taught me a whole different way of living by a different internal compass. It taught me to live more instinctively. And to connect to my breath, because it is this that interconnects everything – and taps you into something that is immense.

TM: Did you feel that was a place to heal – the water? You’ve made it such a big part of your life now.

TC: Totally. I think it was quite a complex relationship at the beginning, as many cold water swimmers or athletes will know. It has to be to guide you through extremities of experience. It is one of the extraordinary gifts in life,

If you go beyond your own limits, you discover a greater potential than you ever believed possible.

Some people said, there’s no way you can do this. It’s dangerous to swim through the winter in those conditions and without a wetsuit. Strangely, that became another line that was very necessary to cross. I had to test myself. I needed to experience that nothing could inhibit you. And it worked. There is an incredible intensity of wellness that comes not just from being in the water, but from its raw temperatures.

There is a cold water glow that irradiates your whole being. I pushed the limits of this. Sea temperatures range in summer from 7 -10 degrees, and wintertime drop to about six degrees. And then there is the weather.

My coldest time swimming was minus fifteen wind chill, so it was very intense. But when you go into that experience it’s a process of training; the resilience stamina and also deeper connection with the conditions you are immersing in, comes from this – you go to a very deep place of stillness and focus. It teaches you a much greater awareness of your internal buoyancy and how deeply important our breath is. You think you’ve given your last ounce, and still it asks for more – and you find that you more to give than you ever imagined.

I committed to this, swimming daily over four years in all weathers. I also started to take my camera into the water. It helped me to go beyond fear. I became absorbed in capturing the wildlife and the close connection I felt with the sea. The light and weather shifts fast; the quality and texture of the water also reacts and when you are immersed, it offers a totally unique and dynamic way to capture and interpret this experience. The sea is a presence that is known and intimate to me. I wanted to express an emotional intensity through the raw challenge of this experience. It was important to me.

TM: I was going to ask about creativity and how nature inspires you. With such an incredible landscape surrounding you, that must help get those creative juices flowing?

TC: Nature is an integral part of my life. It is my companion. I like to wake early with the dawn the light, glowing over the horizon – it is the first presence that you turn to. You start to notice at different times of the year how that changes and how those confirmations of sun and moon and mountains and weather shifts with each season. It becomes an instinctive part of your fabric. It swiftly became a kind of ritual.

I always have my photographic and swim kit ready, so you just heat up a flask and off you go. I would have checked all of the weather and tide tables the night before. But there is always an element of surprise. It is the particular light on the day, that decides.

I like to be in the water, before the great lift of light comes – either the sun rising or the moon setting or vice versa. Folk often talk of the great calling of bird life on the water. And yes, there is this – but that comes later. First there is an incredible shift in the water – the sea exhibits a muscularity and presence that is breathtaking. When you are drifting, film camera in hand you have to attune to this. It feels like the sea is flexing its muscle and there’s this great lift of tide that carries you with it. Above, an arcing dome of water, often with intense wave activity, and just beyond you’re staring at a great ball of fire that is rising that is the sun, or a brilliant amber moon that is setting. It is this gathering of the water that is incredibly moving and beautiful.

Afterwards, about 10 or 20 minutes later, the birds start calling and you’re in the midst of this activity – you’re filming and photographing it, and yet as an integral part of it it absorbs you. Interestingly, the wild bird life is no longer scared of you, because you are in and of that shared element. It is transformative. And maybe it’s this that took me into some truly fierce conditions, to be part of it – it is not just rewarding creatively, but it is cellular. It is forged in you forever and I feel so grateful for that.

TM: You mention the wildlife there, you swim alone, but you’re never really alone with all the life in the water. Tell us about those encounters you’ve had when swimming…

TC: I love swimming in rough conditions. It tests you and brings you closer to your own animism. This is brought alive by interacting so closely with the wildlife – smaller common seals, larger Atlantic seals, porpoise and great shoals of fish. Often when I’m out filming or swimming there will be sea eagle diving down and taking fish, that’s really extraordinary, those really massive wing spans and talons lifting their catch. There are golden eagles and all of the other more usual bird life, cormorants and guillemots, geese and many other birdlife .

The real drama comes in the winter months and that’s my favourite time for swimming when the conditions are but a lot more intense. The big migrations are underway – the tiny goldcrest starts to appear in the woods along the shoreline and that generally pre-empts the migration of woodcock, around the full moons of November and December. These birds have come all the way from Siberia, across a great expensive void and water and intense weather conditions, it’s really extraordinary to see them landing on our shores.

TM: Is morning your favourite time to swim?

TC: I think so. You’re just up and out and there’s nothing stopping you. It feels like everything resets and you’re ahead of the day. Anything that you might perhaps have been fearful or anxious about suddenly feels infinitely simpler – after you’ve filled up on that bigger experience, everything else falls into place.

I always like to stay flexible and I don’t like to rush a swim, otherwise you feel like you’re limiting the experience. If things are front loaded with work, then I’ll go towards the back end of the day. Sunrise and sunset, moonrise and moon set – these are the times when the light and wildlife is most interesting.

TM: Something that echoes through the book is that notion of looking to the sky. Is that something that you still do?

TC: It is. I tend to look to the sky first, rather than a watch. It helps not just to familiarise with timekeeping in nature, but also, really just to place yourself within your bigger framework I suppose.

It’s important to notice the world around us. We can do this wherever we are. Looking at what the birds are doing, what are the trees doing, where’s the wind coming from, are the birds moving in that direction or a different way? Asking questions. It is important to wonder. Sometimes we forget to do this. The light and the cloud formations are important. They help you to track the seasons and the smaller shifts throughout the year.

I noticed this when I was watching the weather and changing light over the mountains. I got into the habit of closely observing the cloud formations over certain peaks and ridges; I noticed how the light falls, and the positions of the sun and moon, changed as the year progressed. When you start to familiarise with this, you start to read the world around you more closely. You can anticipate what the weather’s going to be doing later in the day.

I think these are all good skills. We hold this knowledge inside us, and our sensory body brings us back closely to this. These are the tools we would once have used without thinking. There is always a wilder instinct waiting for us to listen. There’s also a safety aspect to this as well. With my photographic work I like to be right in the scuff of the water. But even if the winds are driving in off a south-westerly and you’ve got the really big water barrelling in, you know that on an uplifting tide you’re going to be pushed back, shoreward, rather than dragged out. These things are important.

TM: How long did it take you to go from city living to being so acutely attuned to the rhythm of nature?

TC: I’ve lived here since 2004, and since 2010 alone. It takes time to acclimatise to nature in its different forms. Its not dissimilar to being a diver – you adjust slowly to the different depths.

The last four years have been perhaps the most rewarding. All of those earlier experiences were tested by my daily swimming and immersion into the landscape, at a deeper level. Time is not really the benchmark. I think it is more to do with our readiness. And our ability to listen to what nature can teach us. Sometimes the most difficult times in life bring us more closely to this. Sometimes we shy away from difficult experiences – but I wonder if actually the greatest wisdom comes from the profound depth of our suffering.

There is a time to really step close to this and not to euthanise it. In the end, only we can do the work that’s needed. That is time when life can open – precisely when you step towards, rather than away, from what you fear. I went to the water when I reached that place. In the water you’re totally out of your depth, but you learn to commit to your breath differently. In the water, there is no place for fear. Time is measured by the depth of your experience. You stay in for as long as you feel comfortable. It teaches a different measure.

TM: What lessons have you learned from your time in the water?

TC: Cold water swimming teaches resilience. It teaches you to fall softly and to take life’s knocks gracefully rather than to brace yourself. It helps you notice to the things you draw back from in life – and it helps you to step more closely to these, so you are not afraid. It also highlights the hard lines our minds can draw – and how simply one breath and then another, one step and then another, can help us overcome these.

It helps to commit to each day – if you have a routine, it keeps you motivated and inspired. It can also keep you safe. It also means that once you have practised the basics, your body is free to explore its full potential – and that is an amazing feeling, because it is when you start to go beyond your own inhibitions and limits, and realise you are more capable than you ever realised. It has helped me to trust again.

Living closely with an awareness of nature, is transformative. It brings us closer to all that is free and wilder inside ourselves. When we start to attune to this, life starts to change – simply because we realise we cannot continue to live as we have been living. It brings us closer to finding a true balance in our lives – and to really feel how our small breath is interconnected with something infinitely greater.

I Am An Island by Tamsin Calidas is out to buy now

Click the banner to share on Facebook