Mental health is finally being talked about in a way like never before, thanks in large to some high profile figures exploring and explaining their personal battles. However, although we seem to be more aware of certain issues, that doesn’t mean they’re being dealt with any better than they have been in the past.

One man who knows more than most, adding his voice and raising awareness on the subject is Luke Sutton, an agent to sporting stars and former professional cricketer for the likes of Lancashire and Derbyshire. He’s first-hand proof that professional sport is a breeding ground for addictive behaviour.

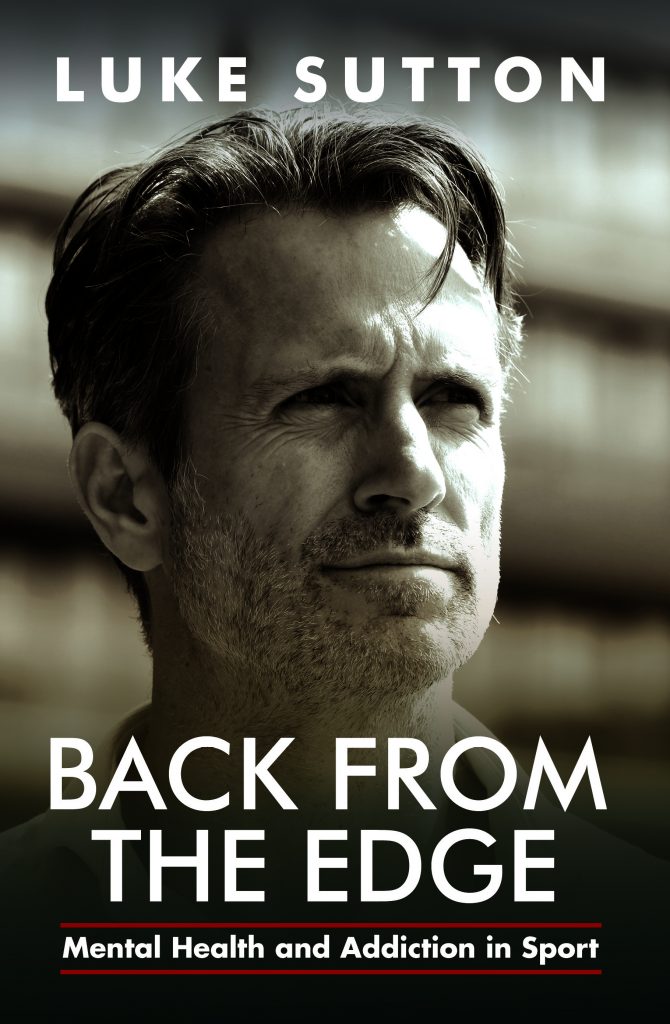

In his candid book, ‘Back from the Edge’, Luke talks about the huge ups and major downs that a high-pressure career in professional sport can bring. He’s refreshingly honest about his own addiction with alcohol and subsequent mental health problems that led to him hitting rock bottom before an intervention from friends and family heralded a life-changing stint in acute psychiatric care.

We caught up with Luke to talk us through his own story and how his life was finally turned around. Luke also tells us how to spot those signs that someone might be in need of help and we get his thoughts on whether enough is currently being done to tackle this serious issue that can affect us all.

The MALESTROM: Tell us about your story? Where did your problems initially start?

Luke Sutton: That’s a really good question. I came from a loving privileged background, I was ultra-competitive and I was quite a high achieving kid, I thrived in a world of success and sporting status. It all felt very natural to me and was the place where I wanted to be in life.

I guess when alcohol started to come into my life at 16, by my early 20s I did know that it seemed to be different for me compared with my other friends. There was a moreish-ness to it for me that I was really aware of. I just kept it a secret because I didn’t really understand it and also, I liked a good night out and was still doing well on the sporting field as a professional cricketer, so there wasn’t really a problem. There wasn’t anything I thought I needed to flag up.

I just moved into this lifestyle of work hard, play hard and I really found myself with that. I thought that was me. It made sense, I was working really hard training for my cricket, I prided myself on training harder than anyone else. But I guess I also prided myself in partying harder than anyone else. They just went hand in hand and I felt as though I had a method in life.

It was my way of being successful in life. Definitely in professional cricket. And I was going quite nicely with my career and developing well. I was captain of Derbyshire and then I eventually moved to Lancashire where I had teammates like Freddie Flintoff and Jimmy Anderson, legends of the game. I was doing well, but I always had this other side to me which I really struggled to keep under control, which was always around my drinking.

I guess slowly over the years everything just amplified. My drinking amplified, my working hard amplified. I lost my girlfriend in a car accident in my mid-twenties and that had a massive impact on me. I still had deep-rooted problems with alcohol, but that contributed to amplifying everything.

It just started to deteriorate and rot away at me. My behaviour got worse around alcohol, everything became more extreme and slowly but surely I was falling apart. To the point that I ended up in an acute psychiatric hospital with a rehab clinic, The Priory in Cheshire. At that point, everything had fallen apart, my family life, my health. I just felt lost and broken and completely and utterly desperate. Things needed to change.

TM: There seemed to be a certain self-flagellation about the way you boozed hard and then trained even harder? You were punishing yourself…

LS: That’s exactly how I saw it. It was like a purge. Often with my behaviour when I was drunk, I’d wake up the next day and wouldn’t be very proud of it and my way of purging that was by my training, achieving. Whether in business or the next match. It was my way of readdressing the balance.

It was a fool’s errand, it was an ever decreasing circle. I wasn’t solving the problem, I was just patching myself up and moving on. Eventually, it just caught up with me.

TM: Did that ever knock on to the cricket? As in you playing under the influence?

LS: It’s a really good question. I don’t think it did. I think in my last year of professional cricket my performances were waining. That might have been the fact I was 35 and I was towards the end. Although I know other players who at that age got a second wind and pushed on till they were 40.

That definitely wasn’t happening to me. I think my lifestyle was having an impact on that for sure. I just wasn’t able to hold it together. Maybe towards the back end of my career, it was starting to have an impact.

TM: Was the pressure of playing professional sport one thing that led to your problems? Or was it not relevant in your case?

LS: Pressure is very relevant, but it’s often the pressure you put on yourself. I really defined myself with what I was doing on the sporting field and in business, that’s how I thought I knew whether I was doing well in the world or not. That in itself is an enormous pressure. If you win this game you’re a good person, if you lose it you’re a bad person.

As I say it, it sounds so off, but that’s how I was operating. It gave me an enormous intensity towards anything I was doing. But at the same time it built pressure up in me and I think I describe in the book.

I was like a pressure cooker and I’d need to escape. Someone would say what do you need to escape from? I need to escape from me. From my head. It was this world I’d created in my own head which brought the best intense results from me. But it was also killing me.

TM: What was that lowest point before others intervened?

LS: That last ten days, starting on my 35th birthday, looking back I was completely falling apart. All I wanted to do is drink. I’d have a big night out, wake up the next day feeling horrific anxiety, then think if I just have a couple of drinks that will sort me out. It’ll dampen everything and I can just crack on with the rest of my day. In reality, I just moved onto the next session and then the next day.

That’s what those last ten days were like and my anxiety was just off the charts. I was a mess, I knew I was breaking down, but I couldn’t see what the problem was. I just knew that I was in a really bad way, nothing more than that final day where I went to go back to my family house at the time to help take my daughter to the hospital and my wife said I couldn’t come.

I said, “why?” She said, “Because you’re drunk”.

And I couldn’t understand it, I thought she was overreacting. But I’d been drinking solidly day and night for ten days and there was no way I should have gone to the hospital with my kid, it was absolutely the right decision.

I was so lost I couldn’t see how poorly I was. My reaction to that was to start drinking red wine in the kitchen and then to walk to the pub which eventually led to me being taken to The Priory. I don’t know where that was all ending. If that intervention hadn’t come I don’t know what might have happened. But it wouldn’t have been a good result.

It’s scary to think about now. In many ways, the time I felt it most was when I was in The Priory, the booze had worn off and I was sober. I thought, “what the f**k has happened? Why am I here!” It’s the realisation of what has become of you.

TM: One thing you learned in The Priory was to show a more vulnerable side. Which seemed to come from observing the behaviour of others in there. Did that play a part in how you came to fix yourself?

LS: I think it was the gift of desperation. When you’re that desperate if someone tells you to go and stand in a field on your head for two weeks you’ll go and do it. I was desperate for sure, I was just still fighting with the solution, but I wanted to change. I think the vulnerability thing, I heard it in others first and I connected and identified.

With Lenny who I talk about in the book, he was the first person I heard speak this way. He stoked the language that was in my soul. It was dark and desperate. It felt like he gave me permission to open up and to really say how I was feeling. Looking back those were huge steps for me.

TM: One thing that echoes throughout the book is the loneliness you felt and not wanting others to feel that way – was that a big motivator in writing the book?

LS: Huge. It was a really big motivator. Obviously the book is about professional sport and I kind of give my warning to professional sport, that in my opinion these problems are not getting better, they’re getting worse. And I think they’re going to continue to get worse. I think in society these issues are getting worse.

We’re in an age of soundbites and social media. There’s so much on conflict and winning and results. I think a lot of people at times feel very lonely in their own head. With their own pressure, their own circumstances. Whether you’re a professional sportsman or not.

I was in a rehab centre with people from all walks of life, from people you’d expect to others you wouldn’t. These issues affect everyone, so for me to write something that someone else might read and go, “I really get that.” Even if they hadn’t experienced my kind of problems, they might just identify with something, that’s a massive motivator for me.

TM: Many believe stigmas around the issue are being eroded thanks to people talking more openly, it’s interesting that you think things are just as bad if not worse…

LS: Your right, I think we talk about it better, but, from a standpoint of professional sport, I don’t think we necessarily understand it that well. I think it’s a really difficult thing to understand. Also with the term ‘mental health’, people often think that’s depression or anxiety. I think mental health is your mental wellbeing, how you are. It shouldn’t have to get to a case where you’re clinically diagnosed.

In professional sports, guys are as isolated as they’ve ever been. There’s as much judgment on them as they’ve ever had. When I started playing cricket your score would go in the newspaper and then the next day it’d be gone.

Now with social media people can be bombarded with messages in an instant around their performance. And it can work the other way around, someone can be lifted up like a God in a millisecond. It makes the pressure of it all really extraordinary.

My fear with professional sport is that the care and understanding are there to an extent when people are playing and that care extends to them when they continue to play well, but what happens to them all when they stop playing and they move on?

Take Gazza as an example. Now we look at him and see that’s really bad, but it was always there, but we just found it funny. When he was playing brilliantly we all thought that it can’t be that bad, but it doesn’t work that way. But that’s a misunderstanding of how we should deal with things.

Recognising signs early and getting close to these people early is key and recognising they could have problems later on. If we see periods where they’re acting out in a certain way, it’s not just about shaming them, it’s trying to understand what’s going on. I think we’ve got a lot of work to do there.

TM: What are the warning signs to spot in others you think may be suffering?

LS: I think the first thing I’d look for is their value system. So, is that deteriorating?

For instance, you have a young sportsperson who has a really close family. Is that drifting away? Is that becoming less important and other things are becoming more important? Are they fixated on social media? Are they acting out in other ways around gambling, drinking and spending money? Are they moving away from that first core person that they were before all the pressure and intensity got put on them?

And if the answer is yes, then that’s when it needs to be looked at, regardless of whether they’re playing well or not. That to me is the great misunderstanding, that if they’re playing well everything is good. I think we have to do better than that.

TM: Do we need to educate people more about how to deal with these issues? People aren’t getting the full picture, are they?

LS: I don’t blame that on the public who don’t understand it, it’s complicated. In the book, I mention phrases like alcoholic and depression. There are good reasons why these phrases are here, but we also need to recognise that when there are labels people argue against them and it starts to become a binary decision. And I don’t think these things are binary decisions.

It should be about is someone’s mental health in a good place or is it deteriorating? Because if it is, we need to start acting now. We shouldn’t have to wait until someone has been clinically labelled as depressed. Things could have been done earlier and I think we just hang onto those labels a bit too much.

TM: And going back to yourself, how are you right now?

LS: To be honest it feels like I’m living a different life. Over the last eight years, it’s not been easy, especially with so many changes to my life. But I don’t drink anymore, I’ve been sober since that day I went into The Priory. And I say that with the utmost respect, I have a healthy respect for alcohol. It’s for people, it’s just not for me.

I don’t lead a good life when I drink and I don’t want to do that. I have to make sure I’m doing things for me that are healthy mentally and I constantly keep a temperature check on my mental health. But right now I’m unbelievably happy in life. And I feel grateful for everything that’s happened to me.

TM: If someone out there is suffering, what advice would you give them about how to best tackle their problems?

LS: Sometimes for the person that’s struggling, it’s really hard for them to reach out and talk. The last thing people who are struggling with their mental health want to do is to talk to people. But what I think we can do is look out for each other. Look out for the person next to you, look out for the people in your community.

If someone is isolating themselves or acting strangely, whether a work colleague or a neighbour, whoever it might be, rather than judge them and look down on them, try and put an arm around them. Just that little bit of care with fellow people goes a long way. I was given that. I didn’t find help, I had people that came and put an arm around me and said that it was ok. That’s what I try and do now and I’d encourage everyone to do it.

Back from the Edge: Mental Health and Addiction in Sport by Luke Sutton published by White Owl is out to buy now.

Click the banner to share on Facebook