Manchester born photographer Kevin Cummins is responsible for some of the most defining images of musicians at work and play ever captured. Immortalising groups and artists such as Joy Division, Manic Street Preachers, David Bowie, Courtney Love and The Smiths, with his pictures allowing fans a unique window to the world of their idols.

His fantastic new book Morrissey: Alone and Palely Loitering, chronicles a ten-year period first photographing The Smiths and after their split their enigmatic young frontman Morrissey, as he transitioned into a solo artist and all-round musical icon.

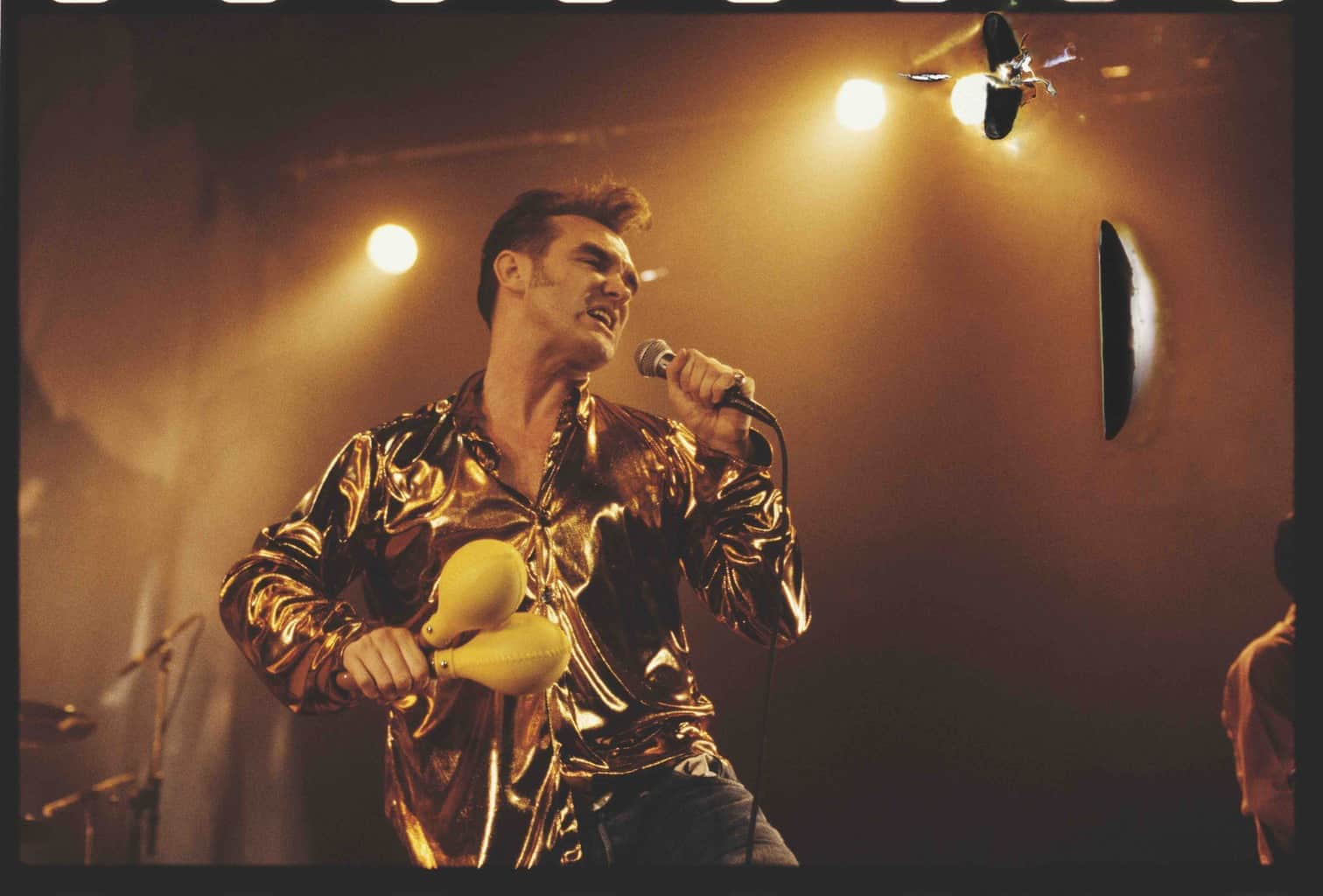

The book features hundreds of previously unseen images, from the beautiful chaos of Moz’s live performances to deeply intimate portrait sessions. Throughout the book, Cummins gives fascinating takes on working and travelling with the Sage of Salford and insights into his photography.

We recently sat down with Kevin to talk about how he first got into photography, the formation of that long-standing working relationship with Morrissey and what is his favourite shot of the singer.

The MALESTROM: How did you first get into photography?

Kevin Cummins: My Father and Grandfather were keen amateurs and they both had – when I say darkroom – it was Mum’s cupboard under the stairs, but they used to print their own stuff and show me how to do it. So I always had that smell of chemistry in my nostrils I guess.

I’d always take pictures of stuff and then, you don’t really think that it can be a career, I don’t know why it became one. I suppose the school I went to, we were hot-housed to go to University, the Arts were always seen as a bit frivolous I guess, they just wanted you to go on and become an academic, so I never really thought photography could be a career.

Oddly even when I was studying it, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, maybe documentary work. I had a really good tutor who just told me to concentrate on things I enjoyed rather than seeing it as a chore, so the idea of taking pictures of musicians was quite interesting, and I think because punk broke when I was graduating that helped as well because I was on hand to document it.

TM: Was it the portraiture that mainly interested you?

KC: Yeah, I wasn’t massively interested in shooting live stuff. Obviously, in a way I am because you’re photographing somebody at work and trying to capture that excitement, and I think that’s quite difficult. You can look at millions of live photos and they don’t tell you anything.

I think it helped I was able to shoot from the stage, and when you’re on stage you’d feel what it’s like to be in a band and so you get the atmosphere, you get the fans in shot. Certainly, in the early days, it was chaos going to a Smiths or Morrissey gig, because half the audience wanted to get on stage.

TM: What was that Manchester scene like when you were coming up in the business? You saw the early days of a burgeoning scene…

KC: I think when you’re in the middle of something you always think it’s quite exciting anyway. I was lucky that Paul Morley was around to document it as well and we used to bombard the music press with stories we made up, stories that were half true and so on, and because they couldn’t be bothered coming out of London they just put it in there.

So although obviously there was a scene, there was a scene everywhere, but we were on hand to document the Manchester one, and Morrissey was there writing letters to every music paper about stuff that interested him.

I suppose also because we had two art colleges in Manchester I think that helped, the city kind of had an arty feel, so I think it’s quite natural that music comes out of that. And we had Tony Wilson helping to facilitate it, he had a bit of money, not much, and he could talk bollocks on TV. He’d say, “this is the most important band in the world” and put a band on that nobody had ever heard of apart from fifty people in Manchester. So we kind of thought we were all in on some big secret.

TM: What was your first encounter with Morrissey like?

KC: Well, when you’d go to gigs you’d all see each other and there was always a nucleus of about 50-100 people that would go to every gig, so everyone was on nodding terms. A bit like two or three of us, Morrissey would be more of an observer rather than throwing himself enthusiastically into it. And I knew people who knew him, like Billy Duffy of The Cult who got involved in a band with Morrissey for a couple of gigs.

When The Smiths started it was a bit of a surprise really, I’d seen them a few times live and everyone was really excited about them in Manchester, in the way that we were really excited about Joy Division and thought the rest of the country was. You’d go to a gig in Manchester and it’d be sold out, then you’d go to Huddersfield which is 15-20 miles away and there would be twenty people there.

It was the same with The Smiths initially, it had a similar feel, it was coming out of the era where you’d have all the new romantic bands and more poppy bands really, then suddenly The Smiths came along and changed that.

TM: How much do you think those early photographs you took of The Smiths contributed to making them more accessible to people?

KC: In the days of the music press, when that was really important, where everyone got their knowledge apart from listening to John Peel, it was vitally important because we were responsible for portraying that band and showing your reader what they looked like and also when you look at a photograph of a band you need to understand what they’re going to sound like.

I felt with The Smiths there was a much more pastoral thing going on, I didn’t want to photograph them in the inner city urban setting that I’d used for a lot of bands previously, which I felt worked for punk, but didn’t work for what they were trying to do. So that’s why we did them in a park around a fountain and it just had a more melancholy feel I guess.

TM: So you felt a bit of a duty to transfer their personality into your pictures?

KC: I always did. When you see the picture of Joy Division on the bridge in Hulme, you look at that picture and you look at the space and the rigidity of the architecture and you know what that band is going to sound like. I think it becomes something that the bands play off.

I think when you photograph a band several times they kind of get picked up and swept along by the pictures. So each time you photograph somebody you’re taking them to a different level. I think photography, certainly portraiture is massively undervalued in areas like this.

You’re taking pictures that the kids rip out of the magazines and put on their walls, these days they make Pinterest boards of them and things like that. I just think you have a duty to inform.

TM: How different were The Smiths from other Manchester bands of that era? They were certainly less hedonistic and they obviously had a strong political stance…

KC: Hugely yeah. We’d had bands that dabbled with it. I felt The Clash kind of were political, but maybe not as much as they should have been, they might have backed a few wrong horses. But punk as a movement itself was quite political, generally. Then you’d get people like Billy Bragg and Tom Robinson, a heterosexual man singing about gay issues, which was also really interesting.

Whereas people like Rod Stewart and all the metal bands and the bands that came before who were playing huge venues with security stopping you getting anyone near them, were just as you said hedonistic bands, who weren’t interested in anything apart from accumulating money and women.

I think The Smiths played a lot with sexual ambiguity and they tapped into that kind of zeitgeist that teenagers go through when they’re fifteen, listening to music, overanalyzing the lyrics and thinking that every word is being written about you. Morrissey was great at writing songs like that because that was the kind of person he’d been. So he could write those and they’d be semi-autobiographical in many ways.

TM: You saw that introspection first hand. What was Morrissey like as a subject?

KC: I think Morrissey has always been great to photograph because he’s very self-aware. I’m not sure he is these days, but he was very self-aware and he understood the medium perfectly in the way that a lot of bands don’t. You can say to a band as an icebreaker, “have you got an idea of what you want to do?” Joy Division’s idea was to stand at a bus stop. Most bands don’t really have strong visual ideas, that’s got to come from you.

With The Smiths, Morrissey always had very strong ideas, not just with The Smiths, but also when he went solo and he was able to call the shots more he’d have loads of ideas for pictures and I’d say to him, “well we’ll try this and we’ll try this” and you’d pick two or three out and sometimes show why an idea wouldn’t work visually as a still image, then we’d bring some of my ideas in and we’d kind of end up with what we got.

Sometimes a picture might not work at all, but he was always up for trying ideas and being quite provocative in photographs.

TM: Was it sometimes the case of capturing a happy accident? One story in your book talks about the picture of him lying down on the bridge and you managed to capture the moment a young boy is looking at him.

KC: Things like that happen. The picture itself without the kid is a nice photograph, but with that kid walking past it just adds something extra to it. Similarly, I photographed Johhny Marr around that time, we were doing a piece for the NME with him taking us to different locations around Manchester, almost like a Smiths tour.

He was stood outside Albert Finney’s Dad’s betting shop and this old bloke was walking towards the camera completely oblivious to me and Johhny and it took him about twenty minutes to walk in between us, he was really slow on his walking stick, I had two frames left and I didn’t have time to change the film and I thought I’ve just got to take a picture that works here and hope that everything fell into place.

As I was about to take the picture Johhny looked at him as if to say come on mate how much longer is this going to take? So it worked perfectly and similarly with that Morrissey picture.

TM: Tell us about some of the first images in the book. There’s one where we see Morrissey surrounded by a cloud of what, on first look, seems to be mist or dry ice, how did that come about?

KC: It was smoke from garden refuse. He just set fire to it in his garden thinking that it would give us a nice soft background, then as soon as a bit of breeze caught it, it went everywhere and he was engulfed in this smoke.

TM: You got some nice shots from it though?

KC: Well certainly the way he looked, and it works brilliantly as the cover of the book and that’s kind of why I wanted a poetic title for it really because I felt he had that look of a Victorian romantic poet on there. Rupert Brooke if he lived in Altrincham and set fire to his garden.

TM: So there was clearly plenty of collaboration on your images. He wasn’t shy to interject with his own proposals?

KC: Yes, and he was very playful as well. I think you can see that there’s a good working relationship going on there. I think with portraiture it’s really important that the gaze of the subject doesn’t stop at the front of the lens, it’s got to go through the camera because your film plane is virtually at my eye. That’s why the pictures work for me… because he’s looking through the camera at me rather than just stopping at the lens. A lot of fans tell me they’re their favourite Morrissey pictures because they feel he’s looking at them.

TM: You helped create an even more personal relationship with the photos you’re talking about.

KC: I think so. Again, I’m not just taking pictures for myself to put on gallery walls, I’m taking pictures for next weeks NME mainly and sometimes prior to that Kill Uncle tour I was taking pictures for the tour brochure. So the pictures have a duty to inform and they’re not just a series of lame pin-up shots, they’re pictures that kind of get you into Morrissey’s psyche a bit.

I think there’s a certain amount of narcissism there with him as well, so you’ve got him lying on the floor making a jigsaw of himself and wearing t-shirts with pictures of himself on. No one could ever accuse lead singers of not being narcissistic, but I think Morrissey knew how to play with that imagery.

TM: Those shots of the fans from the Wolverhampton gig are brilliant – you must have been happy when you got the shot of the fan hugging Morrissey, with Morrissey looking down and security guard ready to pounce…

KC: That gig was astonishing really, again it was Morrisey pulling the strings perfectly because admission for the gig for everyone was free, but you had to wear a Morrissey or Smiths t-shirt. So consequently you had an audience of about twelve hundred people, every single one of them is wearing a t-shirt with a reference to you on it. It doesn’t come better than that I don’t think.

I was shooting from side stage, it was chaos, people were up on stage all the time and all they wanted was a five-second hug. That one worked perfectly because it’s framed on the left with one of the security guards being quite gentle holding on to this person to make sure they don’t knock Morrissey over.

Right through the book in different places, so Japan, the States, there are pictures of people climbing onto stage, hurling themselves at him, being carried off, holding onto his legs so he can barely move and Morrissey kind of just stoically gets on with it as well as wearing the most rippable shirts imaginable that must be designed so as soon as someone touches them they tear.

He really understands how to be a star and I think some people don’t. Some people do it and are genuinely surprised the way the audience responds to them, but I think Morrissey has always understood his audience and because of that there’s a great relationship between him and his fans.

TM: You’re in a unique position in as much as you’ve seen firsthand perhaps as much as anyone who isn’t Morrissey the sheer devotion of his fans, he’s almost worshipped like a deity and you’ve seen that outpouring of emotion that must have been overwhelming at times…

KC: Hugely so. There are incredible moments between fans and bands. I’ve toured with loads of bands of different stature, even shooting Bowie live or U2, and I’ve spent time on the road with both of them, but I’ve never seen anything like a Morrissey gig ever.

Which is why I was interested later to explore the devotion of the fans and do the tattoo bit in the book. Most people when they have a band tattoo they have a logo or something along those lines but with Morrissey, it’s almost all lyrics and it shows how important that is to them all.

I spent about six years shooting those on and off and lots of people sent me really intimate emails telling me why they’d had a certain lyric tattooed and just opening up.

I think there was a lot of trust with a lot of the fans because a lot of them know me from seeing me going to gigs over the years and also because I’ve shot Morrissey so much. They told me some really personal stuff and that helped to inform what I was shooting and why I wanted to do that.

The only other person who I think is similar in the sense that his fans have the same sort of devotion to is Ian Curtis and the stuff that people leave for him on his grave.

Outside of music you get that with certain icons like Sylvia Plath or in the States with James Dean, but there aren’t that many people that attract that sort of devotion, certainly not many who are still alive. Going on tour with Oasis there’s a mass hysteria around stuff like that, but it’s nothing like the Morrissey thing, I think it’s unique in music really.

TM: What’s the one picture from the new book you feel captures his essence most?

KC: It’s quite hard because I feel there isn’t a weak shot in the book. We did a tight edit, I could probably have done about five volumes. The shot I really like, and I like them all, but probably my favourite is the silhouette under the iron bridge on the cobbled bit, which I used on the cover of the Manchester book I did.

I think it tells you a lot that photograph, the fact that you instantly know it’s Morrissey and it’s in silhouette and you can’t see his face is great because it shows how that level of iconography works and also its got the Northern elements of the bridge and the cobbles.

It could be a picture of Billy Fury, it could be the cover of Room at the Top, it screams Northernness to me. I think that kind of sums him up really.

TM: What’s been the biggest influence on your career? What have you been affected by?

KC: Lots of things. I think you’re affected by your upbringing, where you’re from and what you’re exposed to early on. Throughout my career, I can admire other peoples work, see what they’re doing and how that works. I think when I studied photography I was really interested in Bill Brandt, Diane Arbus, and August Sander because they were doing the kind of portraiture that massively interested me.

They all helped form the way I looked at photography, but I feel every artist draws from each other. In the early 1970s when Annie Leibovitz went on tour with The Rolling Stones, suddenly there was a connection between the photographer and the musician and you were getting live shots that were really interesting and vibrant.

Leibovitz got in there with a 35mm camera and made it work. That kind of influenced without people even understanding that it had influenced. It probably influenced the next generation of people who worked for the music press.

TM: We’ve talked about working relationships, was it a friendship you’d say you had with Morrissey at the time?

KC: I’d say it was friendly, professionally friendly. I think the major, major problem you can have when you work with musicians or actors or anybody slightly out of your remit is to think that you’re their best friend. I worked for a long time with lots of warring factions like Morrissey and Marr, Hooky and Bernard, Noel and Liam and I get on with both sides because I’ve never taken sides.

You’ve got to have a good friendly professional working relationship with people. Once you start giving them your phone number and inviting yourself round for Sunday lunch it’s game over really.

TM: Does it affect your actual photos if you don’t like your subject?

KC: Massively it does, yeah. I’ve photographed a couple of bands who I’ve not liked and haven’t liked working with. I’ve been pretty fortunate that I’ve always been able to pretty much choose who I wanted to work with. It wasn’t like that when I started, I’d be sent off to photograph everybody, but as your stature increases, you tend to get the pick of the jobs. So I’ve worked with people I liked working with, it was rare I got commisioned to work with a band I wouldn’t get on with.

I went to go and photograph Duran Duran once and they were a nightmare because they just couldn’t be arsed doing anything and they were all staying in separate hotels and couldn’t be bothered coming down when we arranged to do interviews. We were supposed to be doing an overnight and we were there for a week and I got half a roll of film.

This was a time when people had mobile phones, but his manager told us he (Simon Le Bon) would only answer requests by fax and he was staying in a different hotel to us and they had to fax him to ask him if he’d be photographed or interviewed the following day and we were told he’d get back to us within twenty-four hours. The PR who came with us was ripping his hair out, it was driving him nuts, he’d keep trying to take us home but we couldn’t as we didn’t have anything, no interview, no photos, it just went on forever.

TM: We always ask for a piece of wisdom you’ve gleaned from your career or even a mistake you’ve learned from?

KC: I think all photographers have made huge errors in their careers. I once photographed Madonna at the Hacienda and made the mistake of letting my assistant process the film. We did them in these big open tanks in the darkroom and the phone rang while she was in there and without thinking she just opened the door to go and answer it, then looked back and saw the film and she thought that looks odd, then realised why that looks odd because you’d never see it because normally you’d be doing it in complete darkness.

So she slammed the lid on and carried on with the processing and everything was fogged completely, bar three frames that were the tightest to the middle of the spool. It was 1984 when Madonna did the tube. And it turned out the Madonna pictures would probably have been the most valuable roll of film I’d ever shot.

She went on to manage New Order so it affected me more than her. But we’ve all done daft things, I once photographed a band with no film in the camera because I was waiting so long for them to turn up and wait for the light to be right.

When it was I enthusiastically shot off 36 frames thinking this is perfect, after waiting for the light to hit the wall in the right spot and then I got to 37 and 38, 39 and thought, hang on a minute, and I felt the tension lever and there was nothing there.

I had to pretend to rewind the film and put another one in and asked them if we could do a few more similar shots. So always put film in your camera or rather memory card these days. But we’ve all done it when I’ve told photographer friends they’ve told me similar stories when it’s happened to them shooting huge superstars.

Morrissey: Alone and Palely Loitering by Kevin Cummins, published by Cassell Illustrated, £30. Get your copy from: www.octopusbooks.co.uk

Click the banner to share on Facebook