The Yakuza are Japan’s notorious and highly secretive organised crime gang, an insular set-up that doesn’t tend to accept outsiders.

One exception to that rule was Belgian photographer Anton Kusters, who after 10 long months of negotiation gained unprecedented access into their world, documenting their lives and rituals for two years.

Anton spoke to us about what it was like being allowed to capture intimate pictures within a criminal underworld and how he learned to lose those early nerves very quickly.

The MALESTROM: For our readers that might not have seen your work, tell us a little about what you try and capture with your style of photography? Is it a form of storytelling for you?

Anton Kusters: I don’t think I’m fixed to a certain style of photography. Of course, there’s a certain style in every project, but at the same time, these “styles” appear to evolve over time as well.

For example, “Yakuza” was my first project and was pure documentary, fly on the wall, shooting literally what was happening in front of my eye/lens.

My subsequent work “Mono No Aware” was the visualisation of a philosophical concept in images, which required a vastly different approach. My third project, which I’m doing now, is almost completely abstract: more than a thousand polaroid images of blue skies, with meaning only derived from context not in the image itself.

I would agree that photography for me is one hundred per cent storytelling: it is a means of expressing what I see, an idea, a concept, a feeling. At this point in my life, photography seems to be the means that I am most comfortable with. But indeed it’s all about the story. You are nothing if you have nothing to say, and it’s the story that the audience will ultimately connect to.

TM: Focussing on your book ODO YAKUZA TOKYO, what were your views on the Yakuza before you came to photograph them?

AK: Before I met them, I thought the same as everybody else: my knowledge came from mainstream media and how they portrayed the Yakuza. I guess I would not be alone in expecting to end up in some kind of Kill Bill film kind of situation.

Of course, you know that a portrayal in novel and film would almost by default be quite exaggerated. But then you are left with the question what it would really look like on the inside.

TM: How hard was it to infiltrate their world? You had to build a lot of trust?

AK: It wasn’t easy. I spent 10 months negotiating with them (with my brother who speaks Japanese) before we gained permission that I was allowed to follow and photograph them for 2 years.

Of course, it’s about building trust, also on our side. I had to be completely comfortable knowing that my family would be safe at any time. From their side, I think they mainly wanted to find out if my intentions were pure (as in do as you say, say as you do), and that I was not hiding anything or had ulterior motives.

Given the fact that I was upfront about what I wanted to do and how I wanted to do it, I was able to take away pretty much any possible doubts.

TM: It must have been something of an honour, not many people have been allowed to photograph them?

AK: I didn’t feel it to be an honour, I was genuinely trying to understand the Japanese culture and the Yakuza subculture.

I’m a slow learner in general, so I went for 2 years. Later I found out that not many people had previously succeeded in following a Yakuza family for that long.

TM: Tell us about attending that funeral…

AK: Attending the funeral I believe was the deepest I could go inside. I was at home for a short break, when I got the call that one of the bosses, Miyamoto-san, had suffered a stroke and that his death was imminent.

He was on life support in the hospital in Tokyo. I pretty much dropped everything and got on a plane to go and pay my respects in the hospital.

After three days they pulled the plug (as is customary in Japan), and because I had flown over, they extended an invitation to witness and photograph the funeral. It was extremely intimate – even though it was grand, and that caught me by surprise because I expected only the latter.

TM: Were there any moments in your time with them where you felt you might be in danger?

AK: No there weren’t, and the reason is quite simple. The very first day I went out to photograph them, I was quite nervous, for obvious reasons. But my sign of nervousness was not taken very well, and the bosses literally told me,

“you are allowed to photograph us for two years. The fact that you are nervous shows us that you don’t feel safe, and this is a sign of disrespect to us. Our word is our bond, nothing can happen to you while you’re with us.”

That made all the sense in the world at that moment, and I became much more confident.

TM: Did you see much of their ritual? Obviously, the one best known to the West is the finger shortening to atone for offences. One of your images shows a man with tattooed hands and a missing digit…

AK: The funeral and the tattoos are the most obvious rituals that I witnessed. Yubitsume (the cutting of the finger) doesn’t actually happen that often (most young Yakuza nowadays even don’t have any digits missing), so I did not get a chance to witness one of those moments.

Another ritual would be the covert training camp, where they recruit young new members. Everything that happens in that place on those days is about ritual and “belonging” to the yakuza family, which greatly appeals to youngsters who already want to join.

TM: Many will initially think of bad when they think of Yakuza and organized crime, but obviously they’re just people, did you see that other more human side to them?

AK: It’s not my place to judge the Yakuza. It was clear to them that I fundamentally do not agree with their way of life, but also I respect that their life choices are their own. And as with any person, there is, of course, a human side to all of it.

They are all men with families and kids, who are carefully shielded from the life of organised crime. The Yakuza are acutely aware of their position in society and the choices they have made in their own lives, and that not all is good.

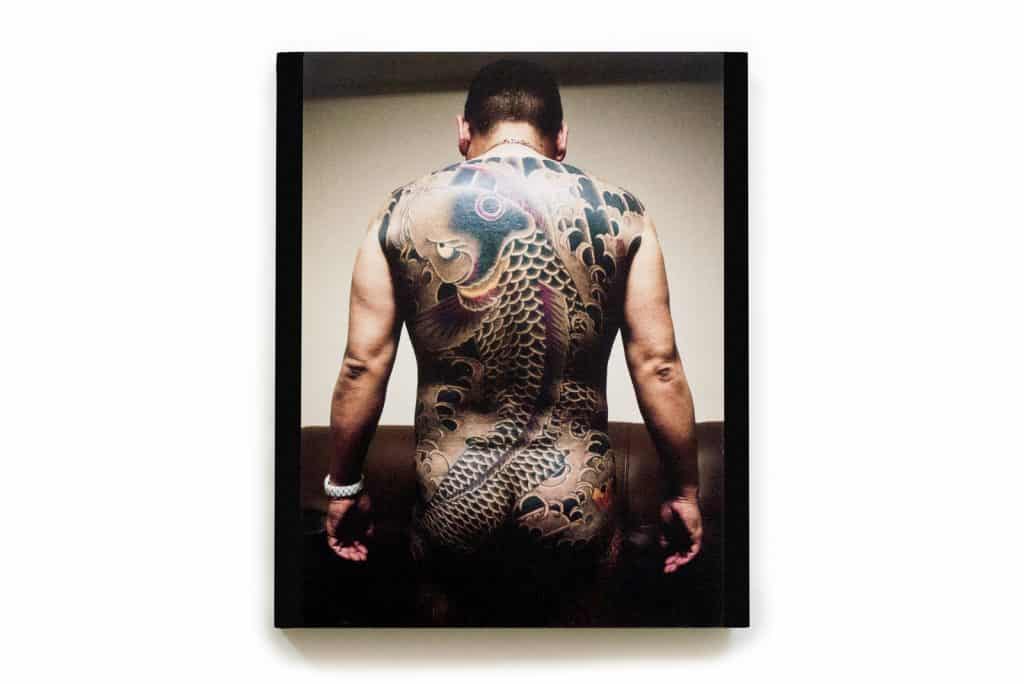

TM: A Yakuza boss was recently captured in Thailand, and was recognized by the tattoos on his body. How important are tattoos in Yakuza culture? They all seem to have them.

AK: Tattoos are essential for Yakuza, but they are not “gang tattoos” like other kinds of gangs around the world, e.g. that everybody has an identical number or a star per rank or a tear per kill.

With the Yakuza, everyone who has a tattoo has a tattoo that depicts something personal about himself. It is a decision from the tattoo master in conversation with that person, what will be the tattooed image or scene.

A tattoo master is also usually not a member of the Yakuza. The only thing that can be derived from the tattoo is that the one who carries it is member of the Yakuza (because of the typical ancient style of tattoo and because of the stigma that Japan has about tattoos in general), the scene depicted in the tattoo is personal and usually not connected to the Yakuza family he belongs to.

TM: What was the image your most proud of capturing?

AK: I think my images of the funeral hold for me the most meaning personally.

TM: What is it about sub-cultures like these that many of us find so fascinating?

AK: I am not fascinated per se in sub-cultures. What I do find immensely interesting is being confronted with my own often too narrow view of the world, and widening it by learning, witnessing and trying to understand.

TM: What wisdom did you take away from your time with the Yakuza?

AK: I think I could sum it up by saying that the world is not simply black and white – like we often like to believe –, but many levels of grey.

The third edition of ODA YAKUZA TOKYO is available to buy now at antonkusters.com

Click the banner to share on Facebook