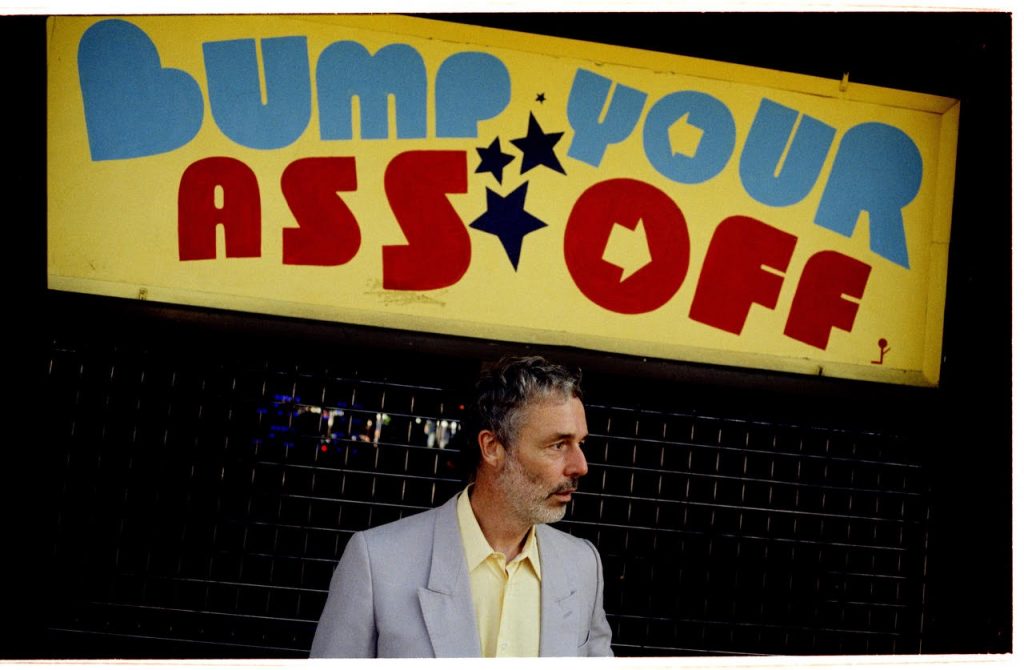

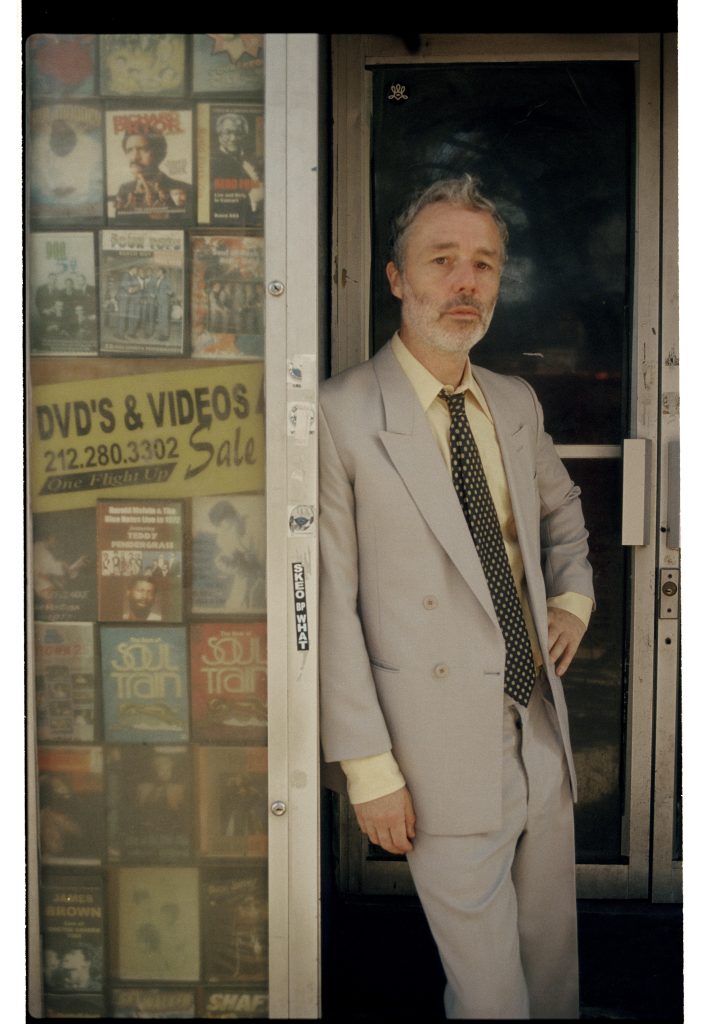

It was four years ago when we last spoke to the lo-fi lothario who is musician Baxter Dury, having just released his 5th album ‘Prince of Tears’ which featured the brilliant track Miami. Currently Baxter is busier than ever having just brought out a sublime best of collection, Mr Maserati, that cherry picks the choicest songs from his 20 years in the business.

And not content with just having one major project on the go, earlier in the year Baxter wrote his first-rate autobiography Chaise Longue, which charted his eventful early years living with his father, the legendary British singer-songwriter Ian Dury.

The MALESTROM sat down with the multi-talented musical maestro for a chinwag about his new record, why he doesn’t like looking to the past and the day Paul McCartney came over to his house for a cup of tea.

The MALESTROM: Your best of collection – Mr Maserati – is great. You must be really proud?

Baxter Dury: Thank you very much. In all honesty I didn’t consider it that much, it was just an extension, because I’ve done a book and I haven’t got another album on the go. It was a space filling exercise, not in a cynical way. But it was quite immediately apparent what should be on it. It wasn’t a struggle.

TM: So it was easy to cherry pick from 20 years of material?

BD: It became obvious partly by popularity, the obvious ones certainly shine. It was really easy actually, it took about three minutes to create a sequence. There’s a few nuanced ones in there, but not that many. Although I guess everything I do is quite nuanced. There are a few clearer ones and it’s nice to be quite clear.

TM: Are you someone who likes looking back? Obviously you’ve had to trawl through your past for your book recently. Is that you? Or do you prefer to be onto the next thing?

BD: Next thing, completely and utterly. I have no interest in listening to the past really. It’s quite nice to do a gig, but I get very frustrated by the past, being shackled by it.

I find the future is more interesting. In a way I’ve been quite lucky as I’ve had this slow burn, incremental career that seems to maintain itself. It hasn’t spiked in any way or gone dramatically up or down. Which has its benefits and its disadvantages. But it always feels like there’s quite a solid future.

TM: Have you felt that evolution over time? Sonically you can sort of hear it, but have you personally felt that evolution?

BD: Not really. As I say, I try and remain unaware. I’m a kind of inflexible plumber bloke amongst shifting sonic changes. But I don’t really change as I don’t have great versatility or melodic range. Except for maybe some of the earlier whispery ones where I was a little bit more falsetto and fragile.

The music around me changes but I pretty much stay the same. Obviously just to stimulate interest from me I have to keep trying to change it. I delusionally think i’m the great hip hop hope. Which is obviously a complete lie.

TM: I think you’ve still got a chance.

BD: Maybe. I think I might get noticed by some great American rapper and they’ll chaperone me. A bit like Dre did with Eminem and people think fuck! Who is this guy?

TM: Who would you work with if you had the choice?

BD: I don’t know. But imagine if some crazy person called MC Blastdown called on me. If that happened I’d quite like to do that. Hang around the Wild West in paramilitary gear.

TM: That would be a good look for you. The new song on the album, D.O.A., is great. It was co-written with your son Kosmo. What was that process like?

BD: We were locked in at home and he’s just a naturally good musician. I just sort of forcibly nicked it off. Like I would do off of other musicians. He was just playing the guitar and I nicked it.

TM: Are you encouraging him to follow in the family lineage?

TM: Are you encouraging him to follow in the family lineage?

BD: He’s just going to do his own thing I think. When he decides to do. I think he’s wise enough not to leap into a perilous situation. Family lineages are weak in music. There’s not a guarantee things will work.

So, I think using your wisdom and being careful about how you approach that is important. It’s quite rare anyone survives, in a pop realm. People tend to emulate their parents and that fades pretty quickly. People get signed and that fades in about twenty minutes when they realise they’re a diluted version of their parents.

TM: Are you still living into flat that you moved back into after previously living there with your dad?

BD: I am yeah.

TM: What memories were evoked being back there at first? Did being back there help with the creative process of writing your book?

BD: No, not necessarily. It’s a mixture. It’s an incredibly structured place, so you’d want to live here. But it holds relatively bleak memories for me in ways. Mainly from the unorthodox upbringing. So it was a conflict.

On one level you’d want to live here as it’s so nice, and has an amazing view. But it’s also messing with the past a bit. I sort of conquered that with writing the autobiography. Now it feels more mine.

TM: Did it help clarify memories of the moments that you had there when you were looking back to write the book?

BD: Sort of. In an arrogant way I think it was more that I did the thing. The process of doing it and feeling some achievement about it. I didn’t appease my history by writing it. It was more the fact I actually wrote a book that was more of an achievement.

TM: Definitely. And you did that during lockdown. Did that help you keep away from the madness engulfing the world?

BD: I just sort of try to ignore it. I’m quite good in a prison cycle. I get up and run around the block, then drink some juice thing. That was quite a helpful thing as I had something to do.

My son was doing his A-levels on a quite serious schedule and I found that was helpful to me as well .. eventually. At first I was quite boundless and lost and then that’s when I really locked in and I found that really helpful. It’s quite addictive actually.

TM: A fairly health addiction ..

BD: Oh yeah, great.

TM: Was there a sense in writing Chaise Longue, even in a small way, that it might stop people asking about your past and growing up with a famous father – you could almost direct them to the book?

BD: If you grew up in that world, a slightly fantasy rock and roll world, you tend to at a young age embellish it without knowing it, just to suit the dinner party criteria. Because people were immediately interested in what you had to sell and I think I always did it so I needed to frame that somehow. That’s why truth is vague in it. Whether it is or isn’t I don’t know, but I just had to put that out. Because I just spent my life probably repeating stories that over time become quite distorted.

I don’t know that it stops people. I tell you what it does, it stops me getting annoyed that people are asking about my father. Because I let that happen, so when I’m doing gigs and people are obsessed about dad, thats irritating. But when I wrote the book I invited that conversation. And I really enjoyed it actually. TM: In terms of the big characters that feature in your book, such as the Sulphate Strangler, they must have had a profound affect on you? Being around those people at a young age can’t not influence you …

TM: In terms of the big characters that feature in your book, such as the Sulphate Strangler, they must have had a profound affect on you? Being around those people at a young age can’t not influence you …

BD: Definitely. I mean I was very blessed in some ways. I witnessed an era that probably can’t exist anymore. Poetically, morally, everything. It merged from the 60s and 70s subculture and I was at the end of its wake.

I saw it and there was some loose parenting that allowed me to experience some of these characters in a way which I was safely guided through more or less. I was really lucky that I could experience that.

TM: Some big names have popped up throughout your life, did you ever get starstruck?

BD: We didn’t really live in a celeb bubble. Dad was quite anti that. But every now and then there were people you’d quite appreciate. Not really I don’t think. We tried to bring it down to a level where there wasn’t any behavioural entitlement. Except for Dad who was quite entitled. Apart from that no one was allowed to be.

TM: Didn’t Paul McCartney once come over?

BD: Yeah. People tended to be respectful with Dad. Paul McCartney did once rock up, but only because he wanted to be respectful to Dad. It was a nice dynamic in a way. So he wasn’t being Paul McCartney when he turned up. He made a cup of tea. He was quite nice.

TM: You’ve created some great characters and vignettes in your songs over the years – do they give you a license to try new things musically?

BD: I guess so. Because it’s a voice to launder stories and opinions through. I really question the process that much of how its evolved. It’s a way of creating interest in a song. There are other things I’m not as good at, like singing, so it’s a way of supplementing the interest in a song by creating a kind of story.

But you mustn’t weigh a song down by creating too much detailed story, it may get submerged. Songs are quite light things. It’s a fine balance. I do really question the process because it’s quite subconscious.

TM: Your last album was really filmic. Do movies inform your work in any way?

BD: I think in the movie soundtrack world definitely, what I like to layer an atmosphere with the story. It essentially sounds like someone talking over a soundtrack. So in that way movies do. The last album I framed a bit like a Kubrick film. Which is really pretentious cause it’s not.

TM: Which Kubrick film?

BD: Lots of them. I went through them all. The album was quite claustrophobic and slightly sinister. It was also very atmospheric which is something he did quite a lot. The whole thing was quite stalkery.

Some of the songs felt a bit 2001, that sort of thing. Open expanses, yet quite claustrophobic. Again that’s really pretentious to even mention Kubrick in the same sentence. I think you just find things to create interest.

TM: There’s a fascination with life’s underbelly that permeates throughout your music – does that partly come from the interesting characters that inhabited your world when you were younger?

BD: I’m sure without knowing it. It all seasons your outlook, i’m absolutely sure of that. All of these things contribute. As I say I don’t sit scrutinising the process, that would ruin it somehow. It’s more from foraging around.

What was nice about doing the book was that it offset some of the pressure around the music. Once you’ve got two things going on you quite like they kind of help each other. That’s quite nice.

TM: From Mr Maserati is there a particular song on there that you feel stands above the rest – or is that like choosing a favourite child?

BD: I like things that are new, because it feels different. So, I like D.O.A. It also proves you don’t have to be in a big expensive studio. It was more or less done at home, it was an interesting process. I like the obvious ones as well. Miami I always thought was quite an achievement. But I don’t overthink it really.

TM: Song collections can sometimes signal a career winding down – that’s not the case here is it?

BD: No. I hope not! As I say I’m kind of in a moderate place, which is quite nice. It’s easy to maintain and it provides a living and it means I’m free to do things. It’s a really nice place to be in I think.

I saw a friend of mine’s band playing at Alexandra Palace recently. They’re brilliant – Fontaines D.C. – they were great, but I was thinking to myself, this is a fucking big place! It’s kind of industry big, but I was really proud for them.

TM: Are you looking forward to getting back to playing gigs?

BD: I am actually. That’s like a holiday to us. As long as I remember my lyrics I’ll be alright.

TM: When was your last one?

BD: I did one this year at a festival, South Facing. But before that it was about a year and a half ago. So, they’ve been scarce. I am really looking forward to it actually.

It’s funny because even after all these years there’s not even a light or a lampshade or any kind of decoration on stage. We could do with a light person. It’s just me being a knob at the front. But maybe that’s all it needs.

TM: That’s all it needs. We like to finish by asking some words of wisdom you might have gleaned from your career – does anything come to mind?

BD: I always think there’s a positive form of competitiveness, if you can find that then you’re away. It’s not an envious competitiveness, but if you get the right bit that gets you going, then you’re unstoppable. But then you always wake up and you’re at it again, I think that’s a positive thing. I’m not sure if it’s wisdom, but positive competitiveness is a real asset.