With a career spanning 35 years and many continents, photographer Jon Nicholson has more stories to tell than most. Aside from his extensive travels on assignment for the likes of the UN, Nicholson was a pioneer in ‘behind the scenes’ in sport, which granted him unprecedented access to top sports stars and teams around the world, one in particular being the legendary Formula One driver Ayrton Senna.

His image of Senna, thought to be the last taken before his death, was captured by Nicholson on the Saturday morning before the first practice at the Imola Grand Prix in San Marino in 1994. This picture remained hidden in one of Jon’s drawers for 24 years and has now come to light to mark the 25th anniversary of Senna’s passing.

With his exhibition ‘Pausing for Breath: A Retrospective’ having just opened at Augustus Brandt, in Petworth, West Sussex, that showcases over 100 pieces of his work, we spoke to Jon about the stories behind some of the fantastic images he’s captured during his career, including that haunting final picture of Senna.

The MALESTROM: Hi Jon, so tell us what got you into the world of photography? How did this all come about?

Jon Nicholson: So I ‘ve been a keen windsurfer for many years, and in 1982 I went windsurfing down in Hayling Island and the sea was pretty rough and I ended smashing my gear. I thought well I’ll get my camera out and take some pictures of the guys windsurfing.

Anyway, one guy was surfing these big waves, all very dramatic and stuff and I took these pictures, and I brought the photos to a windsurf magazine and they used them, and I thought, although I had no aspiration to be a photographer, maybe I could do this for a living and it sort of went from there.

TM: So you weren’t professionally trained?

JN: No, not at all. I was self-taught. A couple of years after, I did eventually leave my job to become a photographer, I’d broken up with my girlfriend, and I thought ‘oh sod it, I’m going to go off and take photos’. I had no idea what I was doing really, but off I went.

TM: Was it mainly sport and action that caught your interest?

JN: I wanted to be a sports photographer at first, but I wanted to be a documentary photographer because I loved that behind the scenes aspect. So I thought if I can do that in sport then that would be the dream job. If I can get behind the scenes with sporting personality’s that would be good news.

TM: How would you describe your particular style?

JN: I wouldn’t say I’ve got a style really. What I wanted to do and it’s very evident in a lot of my pictures, is it’s all about access; it’s all about using short lenses. So, my go-to lens is a 28mm lens and then I use a 35mm and a 50mm, and a 50 is probably the longest lens I have used for probably two-thirds of my career.

I use Leica cameras, you know it’s that Rangefinder, they’re very small. Now I use a small Nikon mirrorless camera which is really good because that just delivers a huge file. So that short lens photography is definitely a style. It’s a reportage, documentary style, which is what I always wanted. But, within that style you can shoot portraiture, you can shoot landscapes, you shoot anything.

TM: They’re very striking images, is there something you particularly look for?

JN: It’s very hard to rock up and just say “right can you sit on this chair, and look out of the window”, because there’s no connection between you. But, if you’re doing a story and you’re working with people and you look across the room and you think, “oh my god that woman, she’s gorgeous” or there’s a guy that looks fantastic, and they might just be planting rice in the fields, but they’re people. As you progress through that relationship building, photographing them working, having a bit of banter, getting in there with them, that breaks down all the barriers.

Wherever it is, here or Indonesia, you still have to have that relationship with the person, then it’s a lot easier to say “you look fantastic can I take a picture”, without seeming a bit weird. Normally people say yes, and over the previous days I’ll be thinking if that guy or lady agrees to have a picture taken, I’m going to stick them in this armchair, or I’m going to get them with the trees in the background at 6 pm, a bit of lighting. So you’re creating your portrait before you’ve even asked the person. It doesn’t always work out like that, but normally it’s okay.

TM: Presumably sometimes, you just stumble across something?

JN: Of course, sometimes you pass something in a car and yell at the driver to stop and turn around, while he doesn’t really understand you and then you get there and it’s all changed, the moment has passed.

With the portraiture, one of the photos that are in the show, a lady from Darfur is telling me a horrendous story about what happened to her, getting raped, her son and husband getting murdered in front of her and how she ran off into the desert, she ended up passing out because she was pregnant from the rape and woke up to find these wild dogs eating her miscarriage!

A horrific, bloody horrendous story and I’m hearing this through my translator, but she’s looking right down the barrel of my camera. And you’ve got to really try and not be distracted when you’re looking at this person, it’s very hard, really very hard to get yourself together.

TM: Tell us about the story of the novice monk, how did that come about?

JN: I was in Laos and it was the last day of the trip, and a guide took me on a boat up the Mekong River, to this island that translates as ‘Lucky Island’ and there was a small monastery on it with about fifteen monks. Nobody goes there because it’s well out of the way.

We were outside the perimeter of this very small temple, I was talking to one of the monks, and then I just felt somebody sit down next to me, you know when there’s a presence next to you? And I just turned to my left and he was just leaning up against a white pillar, and I looked at him and he was just giving me that look that’s in that picture.

I thought “oh my god”, so I put on a 50mm and turned to him and he didn’t move, he just did not move, he just sat there and I took I think three pictures, and I looked at them on the camera and I thought “oh my word, that face, that’s quite a picture”. Obviously, that camera only shoots black and white, so it’s a great, great image. You look at it and you can just see so much worldly knowledge.

TM: It’s a great photo. With all the travelling you’ve done, is there a location that stands out above the rest?

JN: Yeah there are a few places really. I did a cowboy project years ago, I love that Texas Panhandle, that Southwest Texas, New Mexico and Arizona sort of Wild West is great. I love parts of India. Calcutta, it’s just a great city with so much going on. In India, it’s very easy to take pictures because there’s so much happening, but actually, it’s bloody hard to sort the wheat from the chaff as it were.

Places like, up in the mountains, Bhutan and Ladakh, are just monumental because they’re beautiful. Forget taking pictures, hiking up the hills to 13,000-14,000 feet and you can see into the Himalayas, it’s just beautiful. But then shooting in London’s great. Down at the beach in Bognor, watching people do what they do, it’s fascinating.

TM: So, how did you get involved with the Grand Prix photography?

JN: So I knew Damon Hill through various mutual friends, that was sort of in his early teens and then it got to a point where he was starting to race cars and I was taking a few pictures and it went from there really. In 1993 he was teammates with Alain Prost and that’s when the media started to take interest in him and he’d ask If I could take these pictures of me and the kids, and I’d do that.

Then the wintertime of 1993 it was announced that he was going to teammate Ayrton Senna, and I said, “Damon we’ve got to do a book, we’ve got to tell the story of this season, you know?” And of course, tragically Ayrton gets killed in Race 3 and the final picture of him was taken that weekend and sat in the drawer for 24 years.

It was really weird because I was just looking in the drawer for something else and saw this box, ‘Imola ’94’, and that picture was staring up at me. I scanned it up and thought, “oh my god that’s ridiculous”.

TM: Maybe tell us about that day and that image?

JN: So we’d spent all winter with him testing and everything because in those days teams could test whenever they wanted. So we got to know him quite well, and observe him and all of this. The first two races he crashed out, the car broke down or he was forced to retire and then we got to Imola.

On the Friday, Rubens Barrichello had a big crash, broke his wrist and then on the Saturday morning I walked into the garage – as you were looking out Damon’s car was on the right, Ayrton’s was on the left and I was standing in between the two. Damon was doing something and I turned around to Ayrton and he was just standing there looking at a monitor, and I just took a picture of him and that was it.

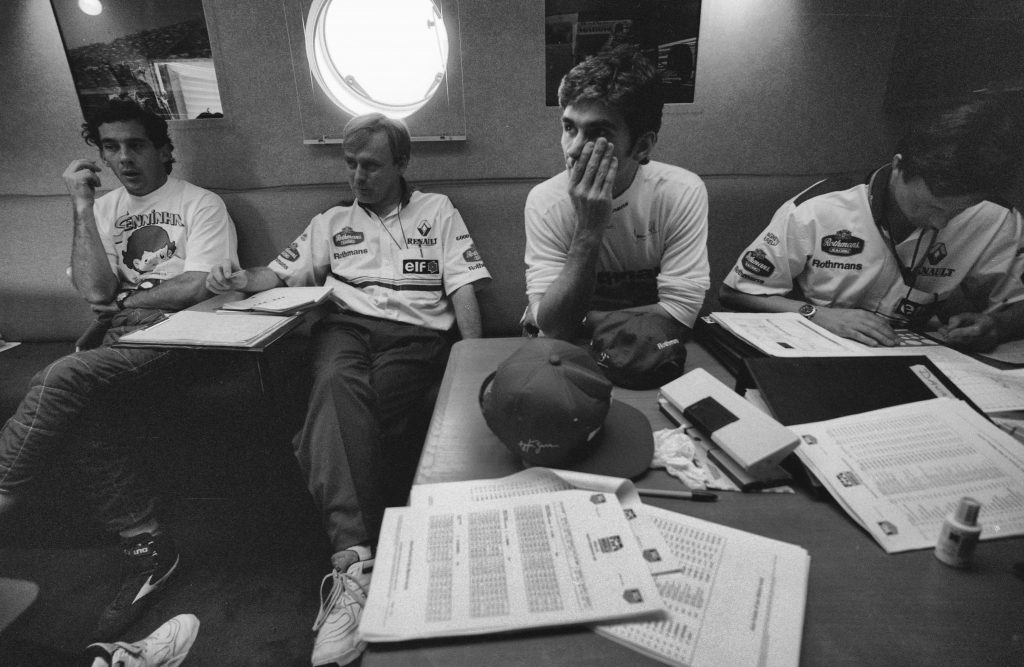

Then later that day Ayrton’s best friend Roland Ratzenberger got killed, which was like horror all round. Then on the Sunday morning we were in the debrief room, and I took some pictures of Damon and Ayrton, and Ayrton was saying “I don’t want to race, they’re making me race” and it’s like what can I do, I’m just a photographer you know, you need to have a word with Bernie [Ecclestone], I can’t do anything.

He had his head in his hands, clearly detached, and obviously later that afternoon he got killed. That picture, any day of the week would just be a picture of a racing driver looking at a monitor, but 24 years later when everybody’s talking about, “did he kill himself, did he this, did he that?” Suddenly you look at that picture and think “wow, you’re already gone”. In hindsight, he’s already away…

TM: Knowing what would happen and looking at that photo, it has a haunting quality…

JN: Some people wonder if people know that they’re going to die, inside their aura, do they know? And Ayrton, all the conversations about did he do it or was it the car? There is a weird calmness about him; even if he hadn’t died he was going to be great.

TM: How did you find him as a person?

JN: He was a very focused bloke, very calm, very focused on what he was doing, but great fun as well.

TM: You were also around the England rugby team, the year they turned pro?

JN: The thing with doing that stuff with Damon at the time, everybody thought this is great, we’ve got to get Jon in to do a bit for us. Nobody was doing it, Sky weren’t there yet, nobody was in the dressing rooms, photographers were more concerned with getting the action.

I had that trust, people trusted me, if it’s alright for Damon, then it’s alright for us. With the rugby guys, I knew Will Carling, I knew a few of the others from some other work I’d been doing, and it was the same thing, first year as professionals, let’s do a book on the season.

You had to do all the banter, it was a case of go up to the bedroom, knock three times and bring a bottle of red, and all the boys were in there. In one debrief session Will, said “Jon if you’re going to come to any more training sessions, you need to wear this”, and he threw an England shirt at me with my name on it and the number 22, so I became known as the 22ndman.

The RFU had got me a tracksuit, Nike had got me some boots and it was all great fun. I’d hold tackle bags and get flattened by Martin Johnson and all that sort of stuff.

TM: What was the highlight from all those sporting events, one must have been spending time with Linford Christie?

JN: I mean Linford was very special, because that was the start of that whole behind the scenes thing. I went out to Lanzarote where he was training and wanted to do a picture on the lava field. I’d done stuff with him before, but, he kept me waiting for three days, he wouldn’t talk to me for three days.

On that third day he came up to me and said, “so what do you want to do?” and I said, “well I’m not going to tell you and walked off”. Later that day he phoned and said they were all going out for dinner tonight, if I fancied coming along. And that’s when we sat down and I told him I wanted to do the picture of him running through the lava fields and he said “ok I’ll give you fifteen minutes”.

So we did the picture and we stayed there for an hour, because he’d never been there before. That was a highlight and that relationship grew into something quite cool you know. Obviously being there for the Senna stuff was pretty amazing in the wrong way, the rugby was a laugh… I think that was pretty cool. I went on to do a book with Chelsea after that which was also good fun to do, but very different, footballers, Chelsea winning the FA Cup. Dennis Wise who was Captain at the time was completely bonkers. It was great, all good fun.

TM: Do you have a favourite image, that’s probably too hard, one you’re most proud of perhaps?

JN: I think the Senna picture has got to be right up there, but there are a lot in this exhibition that are really special to me. There’s one that I took in 2002, that was one of those situations where I literally saw them running across the desert, jumped out of the car, got in front of them and took half a dozen pictures.

TM: We often finish by asking for a bit of wisdom you’ve gleaned from your many years of experience?

JN: Firstly I would say you’ve got to do the small jobs well. As a photographer starting out, if somebody asks you to take a shot of Joe Bloggs in the car park, make sure it’s a bloody good picture. I think the old adage of the more pictures you take the better you’re going to get. It’s not the sort of thing you can just do at the weekend.

Probably the greatest bit of advice I ever got, was from an American photographer who once said – like with Linford running in the lava fields – he said, “Jon you come up with all these great ideas, but can you actually do it?” And I thought, “oh god” (laughs). I can dream it all up, but can I do it? I guess the point is, you have to be able to deliver on those promises.

Also, don’t be shy, have aspiration, and the more pictures you take, you’ll develop your own style.

Jon Nicholson’s exhibition ‘Pausing for breath. A retrospective’ runs till 10 August 2019 at Augustus Brandt, Newlands House in Petworth. For more info visit: www.augustusbrandt.co.uk

Click the banner to share on Facebook