Chris Scott may not be a name many of you are familiar with, but if travel with a twist is your thing then Chris’ knowledge and expertise are a must for anyone thinking of venturing out into the great unknown. With nearly 50 adventures across the Sahara to his name, countless books from well-researched advisories regarding the nuances of desert life to practical help guides, Chris has become the go-to guy when it comes to adventure travel.

Whether he’s advising on TV projects like Sahara with Michael Palin or National Geographic shows, updating his award-winning guides or exploring hidden lakes and rivers down under, adventure is never far from his mind. We caught up with Chris to find out where his love of travel came from, whether it remains safe to explore the Sahara and why experiences are the new big thing in the industry.

The MALESTROM: So Chris tell our readers a little bit about yourself and where your love of travelling stemmed from?

Chris Scott: I can thank the scouts for showing me the appeal of the outdoors and the benefits of self-reliance. The particular troupe I was in was a little more paramilitary than the regular English scouts; more about flour-bombing rival summer camps and tough mountain walking than helping old ladies carry their shopping. But the saluting and oath-swearing aspects weren’t really for me, so I left.

Around the same time, getting a moped and a 250 soon after revealed the exhilaration of go-anywhere-anytime freedom which any pre-smartphone teenager will recall. I soon learned that the lower-speed skills of trail biking held more attraction than belting along the highway into a premature grave. This was the late 1970s when a laughably easy motorcycle test and the advent of 130-mph superbikes led to hospital wards and morgues spilling over with young bikers.

TM: You’ve written so many books about travel, guides etc, but The Street Riding Years is a little different – tell us a bit more about that?

CS: It’s a memoir set during an interesting time in Britain. Economists and historians describe it as the end of the post-war consensus – a boom period of rising living standards which managed to spread relatively equally through British society, rather than the growing polarity as reported now.

I recall Britain in the late Seventies as a far bleaker place than what’s followed with the 2008 economic crisis. The flower-powered party that was the Sixties gave way to Marxist and IRA terrorism, riots and rampaging fascist groups, corrupt and racist police, blatant miscarriages of justice, bolshy OPEC members and unions, let alone Cold War tensions.

But on the bright side the music was great and so were some movies. Bikes too were entering an era of sophistication. In the middle of it all, I found myself 19 years old, living in a Central London squat while earning more than I knew what to do with as a motorcycle mercenary.

TM: In many ways, it’s as much about getting to grips with adulthood and the big wide world as anything else?

CS: At that age and in that era, you just lived by the day. I suspect with a future less certain than it has been for some time, it’s the same now for those in their early 20s who lack a bombproof aspirational strategy.

It’s a ‘drop-out’ or ‘wait-and-see’ option which we’re still blessed with in the affluent West; no matter how bad things might be you can always scrape by on the fringes of society without being seen as a threat and getting dragged away in the middle of the night by government militias in balaclavas.

It took a while to realise adulthood and wisdom doesn’t occur at statute-sanctioned thresholds like 18 or 21, but you make your way in the world as best you can. The key is being able to capitalise on some small chink of opportunity you might stumble across which chimes with your aspirations and interests.

TM: What was London like back then under a Thatcher government, was it lots of people trying to make a fast buck?

CS: It was, and it included us leather-clad ratbags, no matter how much we liked to consider ourselves as renegades and outlaws. London and the South benefitted from Thatcher’s ascendancy much more than the North where the traditional but now inefficient or uneconomic heavy industries were based, and where the record unemployment really hit hard. Across the country there was a definite polarity: you were either in Thatcher’s camp or far outside it. Sound familiar?

The unapologetically self-centred Yuppie was the much-mocked emblem of the time; it was the start of a re-divergence of wealth which they say had narrowed in the 70s. Extravagant and ostentatious spending was in, and that included ordering a now-trendy bike messenger to pick up your contract, portfolio, artwork or just your sushi lunch – small but urgent deliveries which could get bogged down for hours in an expensive taxi.

Throw in a postal strike by a soon-to-be-doomed union, and we were working up to 12 hours a day. It was the same no-benefits gig economy of today but no one felt hard done by. Already by then, I could look at all that status-driven acquisitiveness with scepticism as buying a flash Italian bike new at 18 had been a quick and effective lesson in how shallow and essentially unfulfilling such aspirations were. I’ve had over 60 bikes over the decades but not bought a new bike since.

TM: And those days of despatching and your love of bikes would inevitably lead to your travels?

CS: It’s actually an interest in travel enabled by a motorbiking background and assisted by an excess income which wasn’t being diverted into a mortgage or starting a family. The job and lifestyle felt too insecure for any of that. Be it for work or adventure, bikes have primarily been a tool to me, same as pushbikes, kayaks or cars.

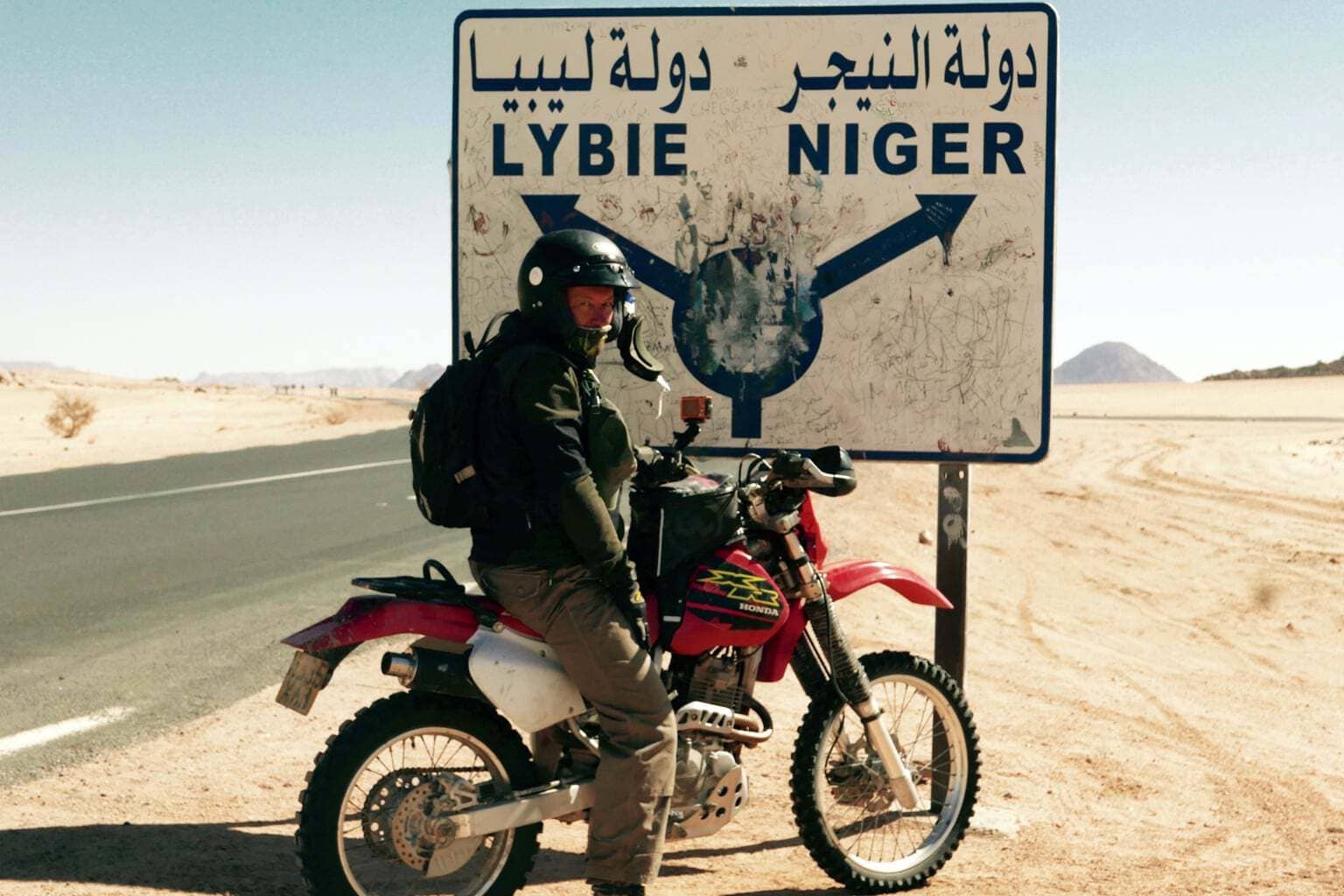

Having got the Ducati out of my system at 18, not 55, I was interested in what these machines could do and where they could take me, rather than what they represented. A visit to the Sahara seemed like a good place to put my new dirt biking skills into practice. Or so I thought.

TM: So tell us how did you first end up heading to the Sahara?

CS: I pretty much threw myself in the deep end. Bombing around diminishing pockets of woodland or wasteland on the outskirts of London was losing its appeal, and a brief go at dirt racing felt too much like the day job.

A friend at work suggested we ride overland to Kenya where he’d been brought up. I ran with the idea – at least as far as West Africa. But as I’ve seen many times since, both in myself and others – the grand inspiration for a trip often fizzles out as reality breaks through or other opportunities come along.

Then, just as now, the preparation and planning aspect was satisfying. The only difference is now I know what I’m doing. While my dirt biking nous held me in good stead, back then (1982) there was very little information on what to expect in North Africa. Or more correctly, this information was near impossible to find, especially in the UK.

I didn’t know anyone who’d ridden in the Sahara but knew it must be possible. Like so many overlanders before and since, I staggered out of a London one snowy evening with way too much of what I didn’t need and not enough of what I did.

TM: It’s such a mysterious seemingly unforgiving place in many ways – what makes it so special for you?

CS: As wilderness environments go, I think the call of the desert is fairly well understood in our culture, whether it’s from the Biblical purging of demons, spiritual transcendence or just a liking for America’s early Seventies hit: [I’ve been to the desert on] A Horse with no Name’ – said to be a metaphor for escaping the drudgery of everyday life in the city. That will do me.

You can add more prosaic things like great weather, interesting geology and pre-history, plus the fact that from the UK, the Sahara is the nearest true, motorable wilderness. I sometimes wonder if I’d grown up in the American Southwest, I’d probably have been happy to stay there.

And as with any form of adventure travel, there’s also a deep satisfaction of learning to do it better while extending your range to ever more remote locales.

TM: Obviously covering such a vast area, political climates change – how has that affected your many trips there?

CS: What I call the Golden Era of Saharan Tourism started coming to an end in the early years of the millennium and probably won’t recover in my lifetime. I console myself by the fact that that anyway, that era was a brief, post-colonial aberration which I happened to catch, and now things are more or less back to a lawless normal (or perhaps a bit worse).

Even with modern technology, Saharan borders are barely policeable lines on a map straddling vast uninhabited regions with few legitimate economic opportunities. Today the rise of Islamists (partly in response to repressive regimes led by elite cliques) as well as the drugs, arms and people trafficking trade, have either closed or made huge areas of the Sahara too risky to visit.

But it is still a massive area and a few regions, like parts Algeria and Mauritania as well as northern Chad, are accessible to the curious and well-informed traveller.

TM: Where would you suggest the modern day traveller should explore and what are the safe areas to go to now? Perhaps that many people would feel it’s far too dangerous to travel to…

CS: Exploration and adventure are as infinite as a traveller’s imagination while being enabled by advances in technology. For example, packrafts (small robust, lightweight rafts), open up a whole new way of getting around on land and water in otherwise familiar regions. We did a trip along a remote river in northwestern Australia a few years ago that was only made possible with packrafts.

The world’s really dangerous areas amount to a handful of well-known countries and so nothing has really changed, especially if you travel with a lower profile compared to say the grand truck expeditions of the 1970s. Places tend to deteriorate quickly – sometimes overnight – but take years to recover.

I don’t believe adventure travel is any more restricted than it was when I started travelling – quite the opposite in fact. It’s just that people get too easily influenced by the pervasive media which thrives on bad news.

TM: What are the perils and pitfalls people should be aware if they are venturing to the Sahara?

CS: Well, assuming you’re avoiding the regions where Al Qaeda and all the rest are currently operating, the traditional pitfalls are usually getting lost and then running out of fuel or water.

I came up with an equation for that once: fuel is distance, water is time. In other words, as long as you have fuel you can keep moving no matter what shape you’re in, but when your water runs out the clock starts ticking, and in summer (a bad time to be in the Sahara) that can mean just a couple of days.

[coffee]TM: What’s the most treacherous situation you’ve found yourself in?

CS: My first trip in 1982 ground to a halt in the trackless desert about 100km from the Algeria-Niger border, just about the geographical centre the Sahara. The bike’s custom-made alloy fuel tank had cracked and the fuel leaked away unnoticed (bikes didn’t have fuel gauges back then), leaving just enough fuel to turn back. Up to that point, I’d already been dogged with problems, and they continued on and off all the way home. By the time I got back, I had well and truly had enough of the Sahara.

But in fact, I’d actually learned a lot about what not to do, and once the miseries were forgotten, it seemed a shame not to go back and try and do it better. After a while, I realised that such tests are all a part of the desert experience for beginners and you have to learn to anticipate them and deal with them. Apart from blind luck (which I also benefitted from on that first trip), it’s how well prepared and flexible you are that counts.

TM: You mention on your site about offering practical desert survival planning that bears little resemblance to info in SAS survival handbooks and TV shows. What is it about that information out there that doesn’t work for you? Is it too unrealistic?

CS: Most of it is aimed at a television audience looking for entertainment, not serious survival solutions. One time I considered laying on a desert survival course in the central Sahara; such a thing could fill up easily with bushcraft folk and the like. But what would I actually teach?

The simple and not so glamorous truth is: do all you can to avoid putting yourself in a desert survival situation in the first place. It’s not like the movies. In a way, my bigger tours for 4x4s and motorcycles have all been survival courses when some participants (including myself) have all limped home injured or having abandoned their stricken vehicles in the desert.

So don’t travel alone unless you’re prepared to accept the consequences. And leave with reserves of fuel, water and navigation aids, plus have the means to repair or improvise the usual breakdowns.

Once you’re immobilised (ie: on foot) and start running out of water, your survival margins collapse. And I’ve travelled in parts of the Libyan Desert where there was no water for an entire two-week trip. Just us and the sand, rock and sky. Collecting half a cupful of condensation per day from your own urine, or flashing a CD at passing airliners is just a waste of energy. How well equipped you are before you set off for a long desert trip defines your survival chances, not how canny you are once up shit creek.

TM: Any expeditions you’ve wanted to go on, but considered too dangerous?

CS: In the 1980s someone invited me to join a Paris-Dakar team, based on my desert biking background. But racing the Dakar principally requires a solid background in off-road racing, not knowing where you can get fuel in Tamanrasset when the main station is out.

Many top racers have ended up crippled or worse. I would have lasted as long as Charlie Boorman. Probably less.

TM: What do you consider the piece of kit you can’t survive without?

CS: In the desert that would be a satellite phone. I know from personal experience that one call to the right person can set in train a recovery that would otherwise not be possible or might take too long.

TM: What’s the worst thing you’ve eaten on your travels?

CS: One evening stuck in Algiers port waiting for a delayed ferry, we strolled into a rough dockside eatery and boldly ordered the plat de jour. What turned up on the plates was unidentified oily squares of white matter among some strands of cooked onion. Once someone identified it as nothing more offensive than tripe we all kind of lost our appetites.

TM: What’s the single greatest travel experience you’ve had?

CS: Desert Riders in 2003 was a good one. I learned the thrill of true cross-country (off-piste) riding, something that had become possible with the advent of inexpensive GPS navigation combined with excellent colonial or Cold-War era mapping.

Crossing most of the Sahara from the Atlantic to the Libyan border in 2006 was another memorable trip, even if my Hilux is still out there in Northern Mali and probably riddled with bullet holes.

But some of the most satisfying trips I’ve done have been camel takes in the Sahara or cycling trips in the Karakoram and Himalayas, as well as packboat adventures in the wilds of northwestern Australia.

Navigating the desert on a bike or a 4×4 can be noisy, hot, tiring and stressful; the best part of the day is stopping for the night. But a bicycle, a boat and of course, your feet bring you closer to the surrounding wilderness without all the racket, paperwork and mechanical complications. In the end, it’s the simple act of wilderness travel that appeals to me.

TM: What’s your favourite means of travel, of course, you also wrote The Adventure Motorcycling Handbook? But, you’re a keen walker/trekker?

CS: To be honest, in the desert I’ve done all I am able to do with motos, cars and trucks. I’m enjoying going further with less. I’ve greatly enjoyed leading or joining camel treks in the Sahara and will be back in Algeria doing that next year.

Even way back in my biking days I knew this is the most authentic way to experience the desert: padding serenely across the desert sands supported by a crew of nomads. You might even call it mobile meditation.

And in the last decade or more I’ve carved out an online niche for myself as an unsung packboat guru – that’s inflatable kayaks and packrafts. Portable boats like these can give a whole new perspective on using the blue bits on a map. And as with just about everything else, in that time technology had evolved, making lighter and more durable boats.

Right now I’m on New Zealand’s northern coast with my packraft, but unfortunately, the forecast is 4-metre swell and 20-knot winds, so I may have to stay inshore.

TM: Has there ever been a moment where you realise you’ve bitten off more than you can chew?

CS: That first trip in 1982 was a leap in the dark which soon degenerated into a fiery baptism. Since then I’ve appreciated how quickly things can go pear-shaped, and so plan accordingly.

Time and again I’ve cooked up some radical trip on the kitchen table only to have it brought back down to earth when faced with a desolate track unrolling before me. And on the water, where I usually paddle alone, I am exceedingly cautious when it comes winds and tides or white water.

TM: What’s the one piece of scenery in the world you’ve seen that’s blown you away?

CS: In southern Utah near the town of Moab is what they call the White Rim Trail, an old uranium prospecting track from the Fifties which pushes out around a rocky headland high above the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers. I’d known of it since the 1980s but only got to ride it for the first time a few years ago and again since.

At around 100 miles long, you can do it in a day on a moto; a car might require an overnight and an MTB a couple of days. Certainly, on a moto it’s just about the best day’s riding I’ve ever done, all the better for ending with a good feed once back in Moab that night.

TM: Tell us where your focus lies these days?

CS: Right now my Morocco biking and camel trekking tours seem to be popular, so I’ll ride that wave until it collapses and I need to change tack again. People’s appetite for adventure and we’re told, ‘experiences’ are as great as ever.

I’m always looking at ways to inch my way back into the Sahara. In a couple of weeks, I’m off to retrieve a fuel cache that was buried for me four years ago under an acacia tree in the Western Sahara. That will be a mini adventure. I’ve always preferred shorter trips of a few weeks rather than months on the road.

TM: Finally, we always ask for some words of wisdom for our readers – from your many experiences?

CS: Do your research then go your own way and do your own thing. It works for me!

To access one of Chris’s many books, find out more about travel in the Sahara or explore the world of Packrafting head on over to Sahara Overland

Click the banner to share on Facebook