Few sports throughout the world have fans who are quite as passionate as supporters of the beautiful game. Those of us instilled with a love for football know how a loss on a Saturday afternoon can ruin a whole week, whereas a win can make all of life’s problems fade away in an instant. For some hardcore fans, these heightened emotions, mixed with an unwavering devotion to their clubs can even spill over into violence.

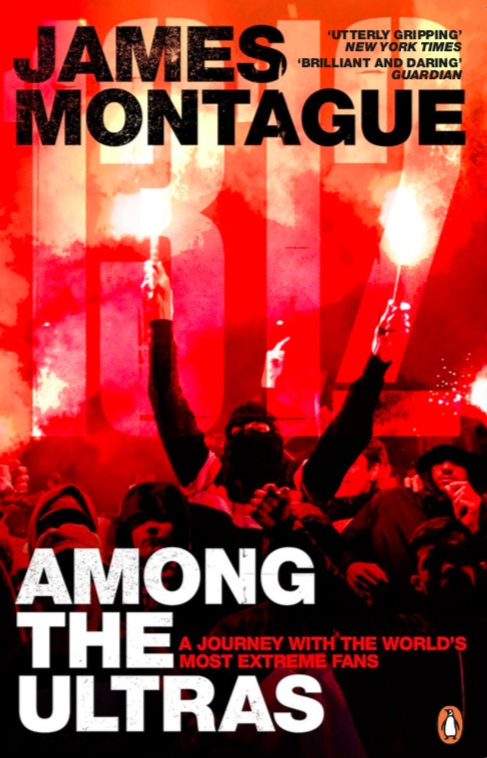

One man who has seen this passion, and indeed violence, up close and in person, is author James Montague. In preparation for writing his superb book, 1312: Among The Ultras, he spent years meeting some of the most feared characters who dwell within this powerful subculture.

On his travels James witnessed all aspects the ultra scene first hand and how it has evolved over the years. From attending organised forest fighting in the Ukraine, to hanging out with the head of Lazio’s Irriducibili ultras and even getting chased by machete wielding fans in Indonesia, Montague immersed himself in this generally hidden world, emerging with a fascinating and revealing book.

We recently had the pleasure of sitting down with James for a chat where he spoke about what it took to get connected with these dangerous ultra groups, the immense influence the different factions have displayed over the years and about some of the seriously hairy situations he found himself in around the world.

The MALESTROM: How did you go about getting connected with the different branches of ultras? They don’t seem to be an easy group to get access to, especially with you being a journalist, a career not too high on their trust list…

James Montague: I’ve been writing about the fringes of football culture, so luckily I hadn’t alienated large amounts of people. When I first started out in journalism I didn’t have any contacts or money, so I would often be going to the places where I would stand in the stadium. So, when I went to West Ham I’d go and stand in the North Bank, that’s where I gravitated towards in every stadium. And that’s where the ultras were and that’s where I started to talk to people. You’re always a journalist, so you’re not going to be taken into their bosom. But over the years I built up enough of a cache with people.

The way it works, it’s not an email address, it’s not a website that your going to, it’s about personal connections with people that can vouch for you. If one person says no then the whole thing is called off. Luckily I knew just the right people at the right time who could open doors. Once one group let me in things became easier.

One interesting conversation I had, for many reasons, was with Fabrizio Piscitelli the leader of the fascist Lazio ultras group who is later murdered. We sat down to talk, and my fixer, who was also my translator, told him I’d written this book called The Billionaires Club, which probably comes from a leftist perspective about how unencumbered global capitals were destroying football. And in the horseshoe shape of politics, I suppose he kind of agreed with that. Even though we were at complete opposite ends of the spectrum. These guys were anti-globalisation, anti-oligarchy. He was a mixture of things.

I couldn’t have written this book 10 years ago and if I’d have tried to write it in ten years time I would have been too old. I was probably just young enough to do it. They were a very young scene and they distrust journalists, distrust the media, distrust police. So, I think it was in the Goldilocks zone where I found the sweet spot at the right time to do it, and also just before the world turned and everything changed.

TM: Mikael is a fascinating character who permeates throughout the book. Tell us a little about him. He seems to have facilitated a lot of the adventures within the book…

JM: Mikael was brilliant. I’d never met him before. But again, this is how it worked. A friend of a friend put me in touch and said that this guy’s the godfather of the Swedish ultra scene. I got in touch with him, he was a bit older, a lovely friendly guy. Turns out he hadn’t been back to Buenos Aires, where he used to live, for years. I told him I’d get him the flight and I was staying in an Airbnb anyway, so there would be a spare bed or sofa to sleep on and we could go and watch Boca Juniors together.

He agreed to do it and the first time I met him was in Montevideo outside this apartment, luckily for me he didn’t turn out to be some maniac. He’s covered in tattoos, has a long beard and long hair and he just turned out to be a lovely guy. We ended up travelling around Uruguay and Buenos Aires. What I loved about him, not just because of the access he gave me, was that he lived and breathed the scene. He was an ultra to his core. He was someone that had sacrificed everything for it. You read books about the American hardcore scene or punk in the UK in the late 70s and there’s all these figures who are given their due, but no one has written about Mikael, who in some ways would have had just as much of an impact in building a subculture. But it’s so anti being documented and so anti the media, there won’t be any stories that survive.

I was really happy for him to let me and of course I ended up going to Sweden, which turns out to be a complete different experience and ends up with a kind of 70 versus 70 brawl. Which he wasn’t involved in. Because Mikael is a pacifist, which was my favourite thing about him. Most people think ultras are just hooligans and they’re not.

TM: It would be good to tap into the genesis of the ultras. You mention In the book about them being seeded from The Torcida Croatia, the oldest organised support group from Hajduk Split in Croatia. And then obviously, you’ve got the Italian ultras, who came to define the term. Where would you trace their roots back to?

JM: In a way it all starts in Italy, but for different reasons. Clearly, the modern meaning of the word ultra, the aesthetic, the language, stems from there. If you go to Indonesia, people are calling themselves Brigata Curva Sud. They’re taking on the Italian phrases. It definitely comes out in the late 60s and grows from there, there’s no doubt about that.

What’s fascinating for me, when you go to Argentina, you go to the Italian immigrant district La Boca. It was the Genoise that came over and they populated that district. What’s fascinating was that the Barras brava evolve really from the 1920s onwards, and, it’s incredible that you have the Barras and the ultras evolve an almost identical type of organised fans support, almost down to the type of songs they sing, the kind of melodies. It’s insane! So, although 68 is seen as the birthplace of the Ultras, I would say Genoa in some ways was even before then, because that’s what was exported to South America. And that’s how football gets into Italy in the first place. You can go back almost 40 to 50 years before then, but Italy, whether you look at Argentina or Italy, is the birthplace for this.

TM: There are some fascinating historical insights in the book, not least the chapter on Uruguay looking at how reserved early football fans were, even dressing in their Sunday best to go to the match and of course that legendary fan Prudencio Miguel Reyes…

JM: For me Prudencio Miguel Reyes was the most fascinating story, the world’s first crazy fan. Nacional, the club in Uruguay, are quite proud of him, but no one really knew about him. Argentine teams are desperate to say that they were the first team to use the phrase ‘hinchador’, to mean fan. Which obviously comes from this guy being the ball blower, it means in charge, to inflate something.

I guess that was part of what I wanted to do. Whenever ultras have been written about, it’s always been in very black and white terms, almost like you’d write about hooligans, if it bleeds it leads. But there’s some rich cultural history there. It also explains a lot about why people act so crazy when groups come together in this way.

So, by uncovering those stories and trying to put it on some kind of timeline, I hoped I would give what is one of life’s biggest youth subcultures the depth I think it deserves. It’s not just singing in a stadium, it can lead to winning a revolution in Egypt, deposing the president in Ukraine, or running a criminal enterprise in Italy, it can go in almost any direction.

TM: I guess there’s a misconception that all fans like this, all ultras are ‘bad’. But they have been instrumental in the likes of the Arab Spring. There’s certainly lots of evidence they’ve displayed a positive influence over the years rather than the negative connotations most people have in their heads…

JM: As it’s a naturally anti-authority space, it shouldn’t be a surprise to people that it would bleed into other areas. If you think of it as a space in civil society, there have been lots of other cultural spaces that have incubated and helped to birth revolutionary movements.

If you think of a football stadium and the curved terrace behind the goal, it’s several thousand, typically young men, who are extremely well organised, extremely anti-authority. They usually reflect the values and concerns that go on in their community. So if you’ve got that as a constituency and the conditions are right, then it can be a really potent force.

Egypt was the best example I saw of that. The biggest club, Al Ahly, had a group called the Ahlawy, which was set up by a guy called Amr Fahmy. His father was the general secretary of the Federation of African football. This is a guy who is obsessed with ultra culture when the study of Italy brought it back.

It started off with something trying to copy Italian and English football culture, because the concerns of all those young people was about the brutality of the police and about the lack of freedom. These are really well organised people in opposition to the police, fighting the police on a weekly basis. When the revolution came, these guys were an important constituency in making sure that the police were beaten in Tahir Square.

So, I’m not saying that every ultras group has the potential to be a revolutionary force. But there’s no reason why they should be dismissed as mere hooligans. In Serbia, Ukraine especially and Turkey where I am at the moment, when the conditions are right, football fans can make a difference. Sometimes that’s for good and sometimes for bad.

TM: I guess they’re also used to some degree as a tool by a proportion of politicians…

JM: One of the things I’ve been Tweeting about recently was this chap in Serbia. I lived there for a few years and wrote about what happened at Partizan Belgrade with the takeover there, essentially by figures attached to organised crime, but also with links to the government. The guy I wrote about, Veljko Belivuk, was arrested a few weeks ago. His protection by the government had been withdrawn for some reason.

In the Partizan stadium they found weapons, they found videos of beheading people. They even brought in the head of the Federation for questioning. They accused him of being involved in wanting to assassinate the president. It’s an absolutely mad story.

You see how these politicians, especially in Serbia, for years have been using, or trying to co-opt Ultras, because they realise they’re useful whether you want hired muscle, a militia, or you need a large group of people to sing your name. Again, Serbia was was remarkably similar to Argentina and Italy in that respect.

TM: They are indeed a powerful force. Do you think this is why their members are so attracted to this way of life? Is it that sense of belonging in a powerful tribe, the sense of community? What would you say is the main draw?

JM: To me, that’s the only draw. I mean, with football, of course people are football fans, they’re not ultras. You can be obsessed with your team. I’m not a hooligan, I’m not an ultra, but I am an obsessive West Ham fan. Being an ultra is something different, it’s a way of life. It’s a way of living outside of societal control. But it’s also about being part of a gang. It’s about locality, community, being part of something that you can touch.

That’s something that humans always want, but in the 21st century, most people’s lives are disconnected. They’re connected online, physically disconnected. I remember talking about this being the biggest youth culture in the world, of course it’s not because gaming is. That’s what kids do. So, when you find something where there’s human community and the depth of connection you feel for the people in your group, you’re going to feel belonging.

Often, when I spoke to a lot of the ultra leaders, a lot of them didn’t really even like football. It could have been following a band, or even a sub-genre of death metal.

TM: What was the sort of interest level in the actual football from those you met?

JM: For the rank and file, it was about supporting your team, your club, your town, your bell tower. Identity in Italy is all about Campanilismo, that you support your bell tower over a centralised Italian state. Your neighbourhood over anything else. So, generally they loved football, they loved their team.

I found the further up you went, the older you got, there was more of a detachment from the game, and it became almost like a youth club to run and then a business to run. Whether that was a legal business or an illegal business. Even when I spoke to Diabolik, he didn’t know who played for Lazio at that moment. There was a time when he did, there was a time when he was so passionate about performances, he would go to the training ground where he would demand to see Lazio’s captain, or find a way to have a meeting with Lilian Thuram to persuade him to sign for Lazio, because he refused and said that you were too racist.

So, as time went on, it had become much more of a thing to manage. To him it was about the group, he didn’t even see it as an ultras group. He saw it as something above that, above football.

TM: You mention the former head of the Lazio ultras Diabolik (Fabrizio Piscitelli) there. We have to talk about that meeting at his HQ where you got to sit down and smoke a joint with him and discuss things. It seemed like quite a sketchy encounter…

JM: On one hand it was quite sketchy. I mean, the moments where he was getting these secret messages. We’re talking and he’s getting these people coming up and whispering messages and passing messages on paper, which he then rips up. He’s up to no good. I don’t know if it was for my benefit that he was doing that. But he was he was clearly involved in some pretty hardcore extracurricular curricular activity should we say.

Going in and meeting him wasn’t necessarily the scariest part. At the club house, when people turned up, everyone would give him a straight arm salute. He gives me a joint because he’s smoking a joint. And he wants me to smoke it. It’s a test. If I don’t smoke that joint then I can leave. You are you are being watched. There’s this ring of people around you. All of his Praetorian Guard watching you, waiting for you to make a mistake. It was quite high pressure, it was quite scary.

But the scariest part was meeting his lieutenant in a tattoo parlour a couple of days before. Because that was the test. That was a test to see whether I was worthy. That was scary. Because this guy, he had ice behind his eyes. When I left I had no idea whether i’d impressed him or not. Luckily, he was fine and the call came through and we went and we met Diabolik. We sat with him for around an hour and a half, a long time.

He was quite charming, very charismatic, clearly very intelligent. I mean, obviously, he was a dangerous guy. Someone open about his racism and anti-semitism. There’s a lot of far right in Eastern Europe, but in Italy it’s a bit different, they wear their fascism a bit more on their sleeve and that was the case there. We left on fairly good terms. And a few months later, obviously, he was shot dead. He wasn’t killed for being an ultra, but he was he was a guy who wanted to live outside the control of the state and that’s how we found himself in organised crime.

That was probably the scariest part of the entire book, the times when you got up close to the moments where organised crime seeped in. We saw, if you go any further along this path, you’re going to be meat. You don’t want to be meat.

TM: You mention in that chapter about his influence over the players. He told you he used to hang out with Gazza when he signed for Lazio in the 90s. The Lazio ultras seemed to have a fair bit of stroke over the players and the club itself…

JM: They effectively ran Lazio. For over a decade they were the most important, powerful and probably the best money making institution for Lazio in terms of marketing and merchandise off their shirts. The way Diabolik spoke about Gazza was like they were best mates, how he’d hang out with him and his entourage and that a couple of them were hooligans. There isn’t a chapter on England in the book but the influence of hooliganism on ultras is really clear. A lot of the chanting and the fashion came from England.

And the power that a lot of groups have, like the Barra in Argentina, is immense. I mean it sounds crazy, why should the fans have any control over new signings? Or getting a cut of the player’s wages so they continue singing their names. When I went to Argentina and asked people about it, obviously they disagree with it, but they made at least a logical case for it. They said, we are part of the game, we make the atmosphere, so we want our cut. That’s essentially how it was explained to me.

That’s how they do it in Argentina. I found out a great story about the Barra of Boca Juniors, La Doce. Some of their top people were put out to keep Maradona and Caniggia on the straight and narrow when they came back for a last hurrah at the club in the 90s. Obviously, Maradona in particular was out and about getting high on the white stuff and they were the security and they expect to be rewarded for that.

In a way you can’t imagine it today because of the way the game is, and you’d probably say that’s a good thing. But it does show this shrinking space that ultraism and fan groups find themselves in.

TM: Talking about the power these groups have. What’s their relationship with the police like? A colleague here at The MALESTROM went to the Roma v Lazio derby 10 years ago and saw the ultras up close. The police essentially turned a blind eye and their backs to any violence they saw…

JM: This isn’t the police’s space. It just shows the power these organisations have in these situations. The police are nominally there to keep Roma and Lazio fans away from each other. Ultimately that’s why I called the book One Three One two, because it’s a prison slang term for ‘All Cops Are Bastards’. It’s something that is a foundational belief for ultra groups. The police are the enemy.

The other thing about this is Lazio fans are well known for being far right. The police in Italy have a large number of members that a lot of research suggests are connected to the far right as well. But it just shows you the power that they had. If they wanted to get in they had the keys to the gate, the police couldn’t stop them. They had the power and it took a long while for that power to be broken. It took massive state control to stop that from happening.

TM: You mentioned the UK before. Obviously we’ve not got that prevalent ultra culture here. But what’s the closest we have to an organised group?

JM: What ultras need is a freedom to operate in some respects within the club, or within the curve, or on the terrace. In English football, especially at the top level in the Premier League or championship, we don’t have that space. You’re a customer and it’s so heavily policed. Also the laws around being a football fan are so ridiculously harsh, you can’t really express yourself or act in any way that isn’t just to turn up and sit there and go home at the end of the game. It’s very difficult for a subculture to exist out of that.

So, in the UK, what you see is that a lot of ultra groups are existing where they can exist, where they do have that space to organise. Take Clapton ultras, for instance. Who I think were in the 8th tier of the London leagues. They were quite famous for the progressive ultras group that exists down there.

In terms of the big clubs, probably the biggest are the Green Brigade at Celtic. They have something approaching what you would expect to see in a big European ultra loving country. They’re a unit that’s very well branded. They look like an Ultras group, they travel in big numbers. They have got progressive politics as well. They’re obviously religious, you see religious iconography everywhere. In terms of a big group that would be comparable with anything in Europe, I think the Green Brigade definitely.

TM: The influence of English football seems to massively permeate the whole scene. You mentioned the film Green Street in the book, especially for it’s influence on the Indonesian Ultra groups…

JM: I make quite a highfalutin claim that I think it’s one of the most influential British films of the 21st century. I’ll stick by that, because when you go to somewhere like Indonesia and see these people who’ve watched Green Street and even the second and third films, which are hard work, they still think this is what English football is like. They dress like it, they take on a lot of the influences, even the music. It was almost in every country I went to.

I remember going to Jerusalem, there were these working class Mizrahi jews who were part of Beitar Jerusalem, this really feared group, and they were singing ‘West Ham till I die’. It was the only English they knew, and it was from Green Street Hooligans. I don’t think it’s a terrible thing that the violence and the destruction has gone, but it is something you have to tell people doesn’t exist anymore. This culture that you revere is kind of gone. It does live on around the world.

TM: Talking about Indonesia, you had some hairy moments there. Can you tell us about those moments where you may have realised you were in too deep?

JM: I guess over the years I’ve ended up in some quite sticky situations. Especially being in Egypt as the revolution was falling apart. In my book, When Friday Comes, I document that and how it all starts going really wrong. At one point I’m in Egypt and I hadn’t been to a football match in 18 months, it very much wasn’t about football anymore and there were moments where you’d get shot at, or had to run for your life.

In Indonesia, I’d got to 40 and was thinking my luck was going to run out eventually. I’d met all these crazy fans, I knew it had a very violent scene, but I thought I’d be ok. Then, because of a bureaucratic mix up about a coach, we had to get off the side of a highway in the middle of nowhere and before I know it I’m getting chased down a motorway by a load of guys with machetes. I literally thought that was it. I’d resigned myself to death. I thought there is no way I can survive this, being surrounded by guys waving machetes.

Luckily the guy I was with made the decision to run across this six lane highway, which we did and we survived! I’ve never known relief like it. Saying that, If there’s one country I can’t wait to revisit when travel is back to normal, it’s Indonesia. I completely fell in love with it. There was a certain amount of violence and anarchy that comes with that, but I found Indonesian fan culture real. This was a space for young people where they could come together and find belonging. Their passion, as dangerous as it was at times, is something I think about often and want to somehow find again. But I think I’ll make my own way to the stadium next time!

TM: The ultras are a far cry from the old school British hooligans – there’s some serious discipline and training that goes on within many of these factions and organised fighting is a big part of things…

JM: One of the big things is that football has become less violent. With the exception of Indonesia and places like that. But with many places, especially in Europe, it’s never been safer to go to the football. That’s because a lot of that violence has been taken out into the forest fighting scene, or arranged fighting, okolofutbola, as they say in Russia, ustawki in Poland, which means a genial meet up.

They’ve almost invented their own sport on the side. Which is mass fighting with strict rules, a kind of honour code system where if someone has been beaten up you stop. Numbers have to be even, there are no weapons, you go into the fight with honour and come out of it with honour. It’s almost like gladiatorial rules. These fighting firms train like they’re in the military. They’re learning MMA skills, judo, boxing, taekwondo. It’s ultra violent and very secretive. You can’t easily find videos online. It’s very difficult to penetrate the scene. When do you have that in the 21st century where you can operate in anonymity like that? It’s impressive. I was there in Sweden and saw some of this, it can go wrong, it can spill onto the streets and bars get smashed up. When these two worlds collide it’s very dangerous.

A lot of the talk last year was around whether football would come back? Will the fans return? What will happen to the ultras? But all the way through I was looking at these hooligan groups on Telegram and I could see these people were still meeting up for these forest fights. That never stopped all the way through. If anything it has thrived. There’s one incident I mention in the book about a 100 v 100 fight in Frankfurt, Germany. You talk about a super spreader event. No one is going to be social distancing and wearing masks during that! It’s mad that this scene exists and it’s so difficult to get access to it. I was lucky to see just a glimpse of it.

TM: You met so many different groups and individuals, would you say ultras around the world are inherently the same breed of person?

JM: I think there’s a type of person who wants to kick out against authority, who wants to find a home with similar people who want to do the same. I remember talking to one ultra in Germany who was more on the left of things. Left and right share the core desire, they’re against police, they’re against control, they want cheap tickets and freedom to have pyro. For him it was a young persons culture, and as a young person you’re meant to be pushing the envelope of what you can get away with. At one point you’re going to have a family, you’re going to have a job, but this the moment in your life when you work it out. Some people go into it deeper than others.

I recognised it, that’s why I was attracted to it. If I wasn’t a journalist and I’d grown up in Italy or Serbia I might be on the North stand. It’s just this desire to kick against the establishment and that can leave you in some very dangerous places.

TM: What was your main takeaway from the whole experience with the ultras? What did you learn from them?

JM: Don’t fall over! I suppose that was the best advice I got. On my first day in Indonesia one guy said to me, “we’re not like other people. If you get chased don’t fall over, because they will kill you. They won’t stop until you’re dead”. I took that advice. I didn’t fall over and I’m here talking to you now.

1312: Among The Ultras by James Montague, published by Penguin is out now.

Click the banner to share on Facebook