Horror author Ramsey Campbell has won almost as many awards for his work than he’s had hot dinners. In a magnificent career that’s spanned over fifty years, he’s brought delights and frights to millions of loyal readers with his novels and short stories.

Having come to prominence in the mid-1960s, Ramsey has become renowned as one of the very best and most prolific writers in his field, being heralded by a host of other horror greats such as fellow novelist Stephen King and director Guillermo del Toro.

We had the pleasure of catching up with Ramsey recently ahead of the release of his new book Thirteen Days by Sunset Beach, to find out how he ended up doing what he does so well, where he draws his inspiration from, and to get some invaluable tips for anyone with a yearning to write.

The MALESTROM: How did you first get into writing horror?

Ramsey Campbell: Really I started writing horror because I loved the field. I was reading it from a horrendously early age. In some ways I was tremendously precocious, so much so that by the age of six, with my Mother’s say so, I was taking books out of the public library on her ticket.

The first book I remember that I ever borrowed of that kind was a book called 50 Years of Ghost Stories. That included stories by M.R. James, E. F. Benson – Edith Wharton, I was reading and getting her even at that age.

We’re talking here about the early to mid-fifties, then you could get most of the classics in one edition or another, there wasn’t that huge of an amount to read then. Now it’s utterly impossible to read everything that’s being written, but then you could certainly swat up on most of the classics.

Funnily enough, one writer who it was very difficult to find was Lovecraft, there was very little Lovecraft in print in Britain, except in the occasional anthology read, it wasn’t till I was fourteen that I got what turned out to be the very first British paperback collection of his stories.

That wasn’t quite my starting point, by the time I was eleven I was already writing complete short stories, which were terrible believe me, but I was still writing them. They at least had some narrative, with a beginning, middle and an end, although they were stuck together from favourite bits of stories I’d read. The most coherent and sustained, which was all of 4,000 words long, which seemed immense to me at the time, was a Readers Digest version of The Devil Rides Out.

When I got onto serious writing was when I’d read Lovecraft in quantity when I was fourteen, this seemed to be the absolute pinnacle in supernatural horror fiction and knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to pay back some of the pleasure it had given me, purely for my own satisfaction. There was no idea at all to send it anywhere, I simply wrote these stories.

It was only when a fellow fan of science fiction, horror, and fantasy, who was also as I was a member of the British Science fiction Association, and I were in correspondence. It was a guy called Pat Kierney, first of all, he asked to see my stories, I was so nieve about what you did that I sent him the only handwritten copy in the mail, had it got lost that would have been the end of all that.

But he duly read them, they were quite legibly written and he asked if he could publish one in his fanzine, also suggesting that I should send them to Lovecraft’s publisher in America.

First of all, I sent August Derleth a letter saying I’d written these stories and I just wanted his opinion as he was the world’s authority, which he was I’m sure. So that was it, I was just sending them to say, “are these any good?” To my amazement, I got this letter back from him once I’d typed them up and sent him a copy, saying, “these need a lot of work”.

By gum was he ever right about that, he also said, “if you will do the work that’s necessary and also write more stories of this nature, it’s possible we could publish a book of them.” That’s pretty strong stuff when you’re fifteen, particularly from a guy that’s published Ray Bradbury and Lovecraft himself.

So obviously I did do all the work and the first of those stories he published while I was sixteen, the actual book came out when I was eighteen and that’s where I began.

TM: What was that moment like when you first saw your name in print?

RC: That was pretty astounding, not least because here I am alongside the likes of Robert Bloch, I’d only recently read Psycho and then seen the Hitchcock film, so it was a transcendental moment you’d say.

TM: Where do you draw your inspiration from these days?

RC: Everywhere, anything at all, absolutely anything. It’s quite often everyday things with the ‘what if’ principle. Your mind suddenly says well what if this might happen. Say you’re passing a phone box, which used to happen, you don’t get them so much nowadays, but back in those days say the phone rings as it often did.

What happens if you picked that phone up? Or what happens if you’re away on holiday and you collect your passport from the desk when you’ve checked in and they’ve given you somebody else’s passport, what then? Both of which led to short stories I’ve written.

The most extreme example, the one I always cite is from Rocky II when Rocky has lost his title and he goes to Apollo Creed asking if he’ll train him to get his title back. And Apollo Creed says effectively, “I’ll give you what you want, but you’ll have to promise me something, but I won’t tell you what it is till you’ve got what you want.”

Of course, it was that Appollo fought Rocky in a ring at the end with no spectators.

But in the moment when he said that in the film I thought there’s something else here, there’s a different story. To be honest I spent the last half an hour of that film scribbling in my notebook and by the end of the film I’d written down the plot of a novel which was published in the mid-eighties called Obsession.

It’s about four teenagers who get that sort of an invitation, although in their case it’s an occult invitation and what happens is that twenty-five years later they have to pay the price. But all of that came out of one line of dialogue in a Sylvester Stallone film.

TM: Do you draw inspiration from horror films as well?

RC: Well I love cinema generally, not just horror films. But no I generally don’t get ideas from other peoples work, very occasionally. I wouldn’t ever watch a film and say I could do better, but I’d certainly see a film and think I could do differently, which might set me off, but again it’s no more film than anything I see in life.

TM: Do you have a favourite horror film?

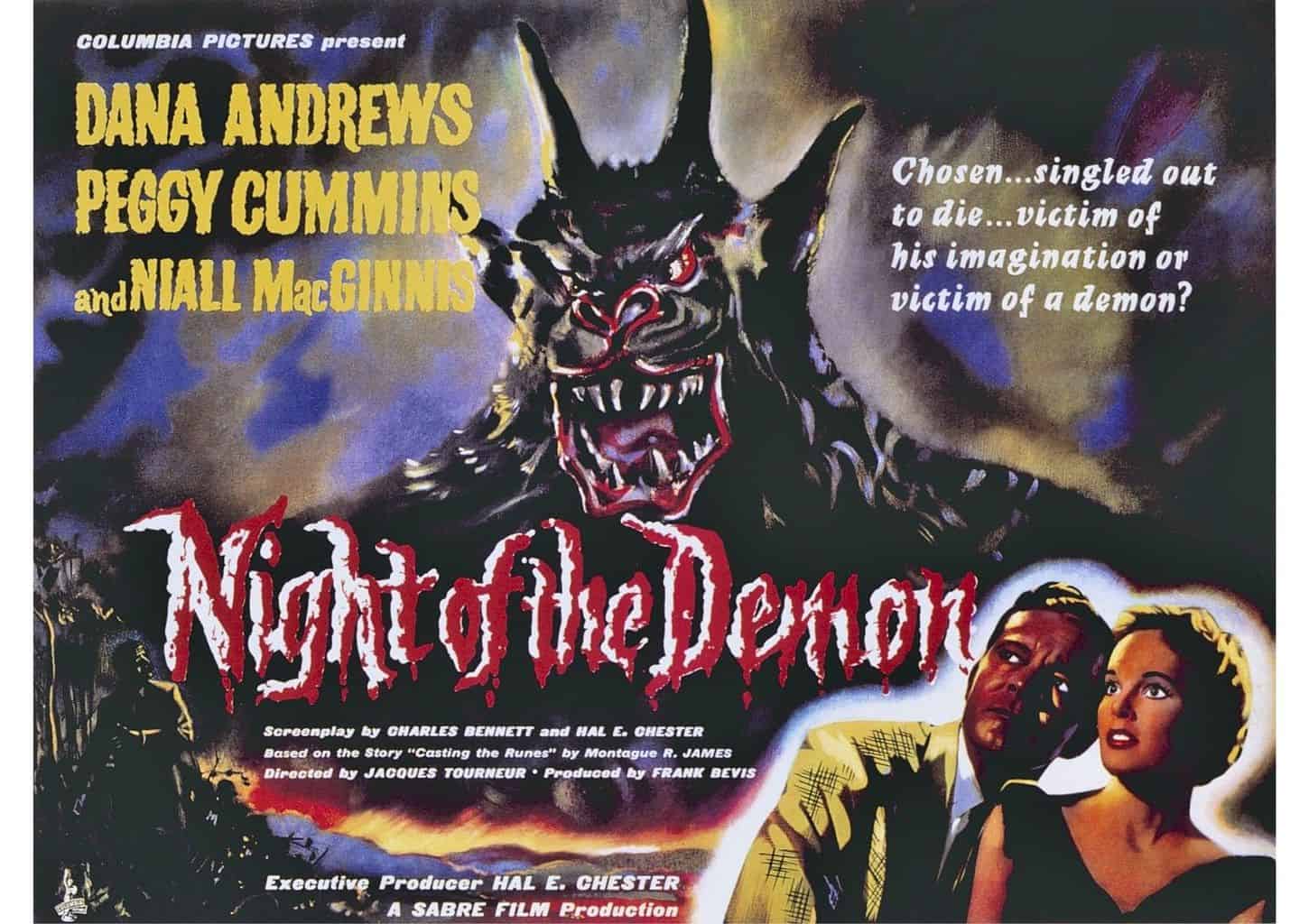

RC: I have an absolute favourite horror film which I love more than any in the field and that is Night of the Demon. It stars Dana Andrews, Peggy Cummins, and the great Niall MacGinnis. It’s based on a story by M.R. James called Casting the Runes, as it happens I’ve just done an extra on the forthcoming Blu-Ray which is coming out this month I think.

So, by far the most horrifying thing on Blu-Ray is going to be the sight of me in high definition!

TM: You’ve written for a number of years so you must have seen tastes change in horror. Obviously different sub-genres have their moment in the sun like with zombies currently, how have you seen those changes?

RC: Obviously the modern zombie starts with Night of the Living Dead and then you have films like the much banned Zombie Flesh Eaters which you can now buy on beautiful Blu-Ray in HMV.

Things have got more graphic, one thing horror does is push further than it has gone previously. At the same time you also get the reaction against that, a creative reaction where other people, other filmmakers go for something more restrained or more suggestive.

You get films like It Follows or Hereditary that are much less graphic. I have a lot of time for both, David Cronenberg’s films are extremely graphic, but I think they’re also genuine pieces of very challenging filmmaking, or Clive Barker’s Hellraiser say.

I always differentiate between the explicit horror that enriches the imagination and the kind that is a substitute for imagination. I wouldn’t be without either kind of horror myself, my favourite is the atmospheric kind as in Night of the Demon or the original Cat People or indeed a film like It Follows that I found extremely effective.

Again it’s suggestive and more eerie than graphic. That’s my particular favour, but I’ll happily watch a Lucio Fulci Zombie film anytime and have fun with it. It’s as much that things go in cycles rather than actual tastes.

Horror seems to have become not exactly respectable but it goes through periods of being unacceptable. So, for example, you’ll have your ‘video nasties’ era where all the tabloids were blaming horror for everything that was wrong with the country for several years and you actually had people saying why can’t we have cosy pictures like the Hammer films, apparently forgetting that when Hammer films like Dracula and The Curse of Frankenstein came out they were getting exactly the same reaction, saying this is going too far and it’s too physically horrifying.

Of course, it was a few years ago now we had the likes of Hostel and Saw, as they called it the ‘torture porn’ genre, that was the last thing to attract the interest of the press. Even that seems to have fallen away, I’m sure we’re going to get retrospectives of them at the National Film Theatre before very long.

I recently edited for The Folio Society, they asked me to do their horror anthology, which I duly did, so I tried to include all shades of horror from the ghostly to the psychological to the physically gruesome to the relentlessly terrifying.

I think I’ve done a pretty good job, my point is horror has immense range – it’s a hugely wide field that goes all the way from the delicate, very subtle like The Haunting of Hill House, to say… I was about to say The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but it’s amazing when you look at that film how little it shows. It’s relentlessly horrifying, but there’s almost no bloodshed. I think it’s because it never lets up that it works so well.

TM: Do you think the less is more element of horror is essentially the scariest? The fear of the unknown…

RC: Well it is probably for me. Although you can look at a film like John Carpenter’s The Thing where the monster, by gum is it ever up there on the screen, and it’s absolutely terrifying. So I think the one thing it comes down to more than any other is imagination on the part of the maker, that’s what’s important, it has to be there in all those forms.

TM: Are there particular scary moments from your books that you’ve had more feedback from readers on others?

RC: Well yes they have, and it’s strange for me, more often than it’s something I’ve thought of as ok, or mildly eery. For instance, there’s a book called The Grin of the Dark, about a lost silent film. There’s one chapter in there where the narrator and his aging parents go off to visit this derelict theatre, which has half collapsed and there’s snow inside because there’s been a lot of snowfall.

There are snow figures in there that appear to move, I finished the scene and I thought, is this perhaps a little tame dramatically speaking in the context of the book?

But I don’t like to try and crank it up and force something to be more frightening, it has to be what it is for me the writer. So I let it go, and it was extraordinary, I had more than one seasoned reader of horror fiction, who genuinely said they had to leave the light on after reading it.

It has to be that less is more principle because there’s almost nothing there in terms of what actually happens, yet there seems to be this sense of upcoming menace that people get from it, which is fine. I’ve long ago concluded the writer can’t control how the reader reacts.

If you’ve been to a book discussion group everyone has a different view of the book you’ve just read, so the writer clearly did not control how people responded to it, you can’t. Even someone like Hitchcock who is the master of directing your reactions, you get everyone reacting differently to his films. What I’ve tried to do is not impose the experience on you, I’m trying to convey to you what it feels like to me and if that gets through then that’s it.

TM: Tell us about your new books, Thirteen Days By Sunset Beach & Think Yourself Lucky.

RC: Thirteen Days I’ll withhold slightly on, I will say it’s about one of the most familiar creatures in horror fiction, that’s what’s at the centre of the narrative. I must say I never thought I’d write a novel about that because I thought so many other people have done it and done it so well.

RC: Thirteen Days I’ll withhold slightly on, I will say it’s about one of the most familiar creatures in horror fiction, that’s what’s at the centre of the narrative. I must say I never thought I’d write a novel about that because I thought so many other people have done it and done it so well.

It comes back to the inspiration we were talking about before. We were on holiday in Zakynthos – the Greek island, one morning we were going on a day trip with a driver in a minibus and we drove to this 18-30 resort not long after dawn that was utterly deserted, people were clearly sleeping off their hangovers.

The guy said, “it’s where the undead go for their holiday, they’ve all gone to bed now and they’ll come out when it’s dark.” I thought, hang on there’s a story here, luckily I had my notebook with me and that’s where this one came from.

So it’s an extended family going to a Greek island that’s recently opened up to tourism, only to discover there’s something strange in at least one of the local resorts, regarding those who are native to it.

They do come out after dark and some of the members of the family become victims of them, except in at least one case, that of the old lady, who might not just be a victim, she may be a beneficiary of it and that’s what makes it complicated.

Think Yourself Lucky is about a guy working at a travel agent in Liverpool who just wants a very ordinary life. He has a girlfriend who is a chef and they live an uneventful life. It becomes clear someone has a blog online that describes a number of atrocious murders that the blogger appears to have committed that are in some way related to our unlucky hero.

The roots of this are in his past. I think what this is really about is the internet and how it lets out the monsters in all of us. Dr. Jeckyll had to take a drug, all we have to do is go on the internet.

TM: Do you have a belief in the supernatural yourself?

RC: I’m not a skeptic entirely no. I tend to look for the natural explanation, but failing that I’ll think maybe there is something more. Certainly, there’s been a few strange things that have happened in this house where I’m sitting now that have given me cause to wonder.

TM: What’s your writing process like? Do you have a set routine?

RC: Pretty much. I’m here at this desk by seven in the morning, but I’m really working from around six in the morning because before I get to my desk I’m working things through in my head. One thing I have learned over more than half a century is to compose at least the first sentence before you start the session so your not staring at a blank page.

With me, the first draft is always longhand, with a pen and an exercise book. Then I re-write onto the computer. It’s seven days a week, that’s every day when I’m doing a new story, that’s Christmas and my Birthday included.

I write till about noon normally, because by that time the energy is beginning to flag a bit. I will do stuff in the afternoon, but it will be different stuff, a piece of non-fiction or a column or review.

If I’m writing a new piece and I go away on holiday or to a convention then it goes with me and I’ll write it there. I try and work it these days if possible that maybe I finish the novel before going away on holiday then take it with me to re-read it and see what needs to be done with it. But if I’m still working on it, it has to go and get written.

TM: How long does it typically take you to write a novel from start to finish?

RC: Most of a year. Maybe five or six months for the first draft, then I’ll do a few short stories in between until I re-read it, and then once it’s been re-read I get to the re-write. So pretty much getting on for a year.

TM: That’s incredible dedication, especially with you being so prolific…

RC: Well the fun hasn’t gone away, nor the compulsion to do it. I’d far rather be doing it than not be doing it for sure.

TM: There are so many lovely quotes out there from your peers like Stephen King and makers of screen horror like Guillermo del Toro about your work. That must be special…

RC: Oh yes, of course. I mean it goes all the way back to Robert Bloch who was very enthusiastic from early on in my career, sending letters and things. Ray Bradbury I actually had a letter from, way back when. Of course, I met all these folks from that generation, I was going to America from the mid-seventies onward and it was The World Fantasy Convention was where I met everyone.

Lovecraft had sadly been dead for decades, but I was meeting all his contemporaries who were still about and we all became friends. So I do feel very strongly that I’m part of the tradition and equally it’s about trying to hand it on to other people.

TM: What would you consider the best piece of horror literature ever written?

RC: Well there are a few candidates. For the novel, it might be Lovecraft’s The Case of Charles Dexter Ward which I’m extremely fond of and it still works for me.

For shorter stuff, I would probably say The White People by Arthur Machen, which I found extraordinarily disturbing. It’s very insidious, there’s virtually nothing there on the page you can point to and say, “yes, this is deeply horrifying.”

It’s an accumulation and the way it’s told in the naive voice of a young girl, who basically seems to think she’s narrating fairy stories she was told by this mysterious governess, but you gradually realise there’s something much darker here. It’s like nothing else in literature.

TM: What tips would you give for budding writers looking to get into the genre?

RC: Apart from the one about working out your first sentence I’d say always finish your story before you write another one. And even if it feels bad, still write, don’t take the chance of falling foul of writer’s block by saying to yourself, I’ll write when I feel like it. It’s much better to write every day while you’re working on something if you possibly can. Engage your imagination,

If you’re going to write horror, write about what frightens you or disturbs you and what you feel might do that to somebody else. Tell as much of the truth as you can from your own experience, of your own observations.

Make sure the characters are believable, that’s the pitfall of too much horror, that the characters behave as real people would not. You’ve got to believe in the characters.

I’m not someone who says you have to like the characters or even identify with them, but they should seem real, that’s all I ask personally.

The fantastic Thirteen Days by Sunset Beach by Ramsey Campbell is out now. Buy your copy HERE.

Click the banner to share on Facebook